Paula Modersohn-Becker

Numbered Thoughts

Sunday, January 12, 2025

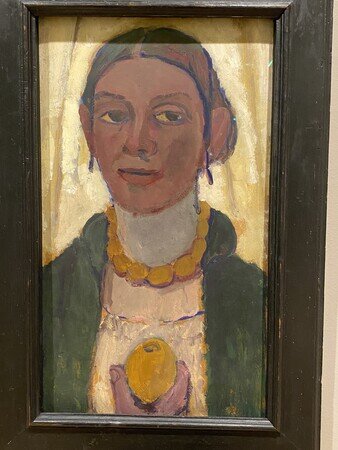

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait with Lemon, 1906-7, detail, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum

I learned of Paula Modersohn-Becker decades ago, writing a piece about Rainier Maria Rilke for the Threepenny Review. Investigating Rilke's Letters on Cézanne they turned out to be bound up with his relationship with, and admiration for, the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker. I thought I would like to know more about her work. Since then, Modersohn-Becker has become much more possible to learn about, and, a few years ago, when I taught a class on Cézanne and modernist writers, I acquired a bit more information. But the exhibition of 2024-25, which was first at the Neue Gallerie in New York and has now taken up residence at the Art Institute of Chicago, has been my first chance at immersion. After brief forays that resulted only in a confused sense of not getting it, I finally made a visit before the holidays where I had enough time to go back and forth within the show, and I began to feel that I was learning some of the keys for this artist. I wrote notes, and thinking back over it, I wrote notes again, numbering them, and re-entered the process, in the order the observations occurred to me within the exhibition.

1. Edges. Often in a darkened line, a blue-purple that might be related to Cézanne, which distinguishes the hand or the face or the hat.

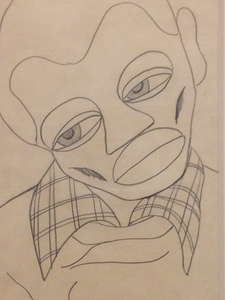

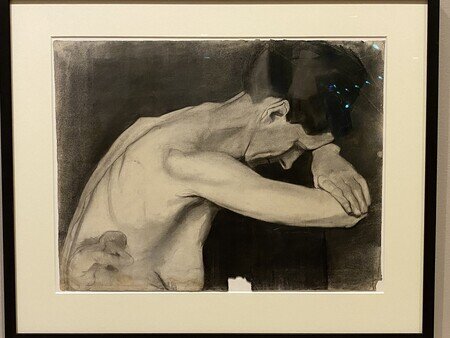

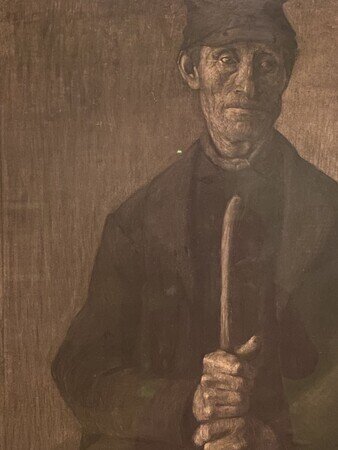

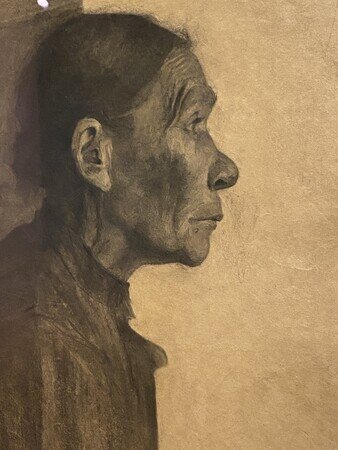

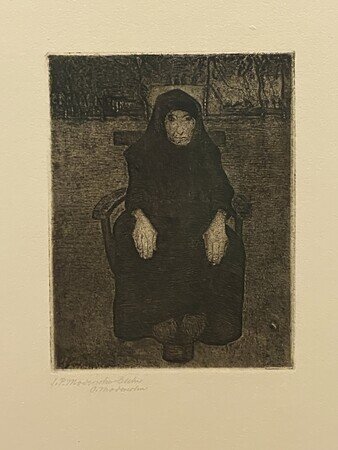

2. 50 large-scale charcoal portraits. Of women, children, the elderly, who lived at the poorhouse in Worpswede. People the artist knew well after she took up residence there. The wall text points out that they all would have had their names in her mind, it is only because she died so young and so suddenly that all the titles have had to become ‘Elderly woman, profile,’ ‘Young girl, standing,’ etc. 50 is a large number, that is a practice.

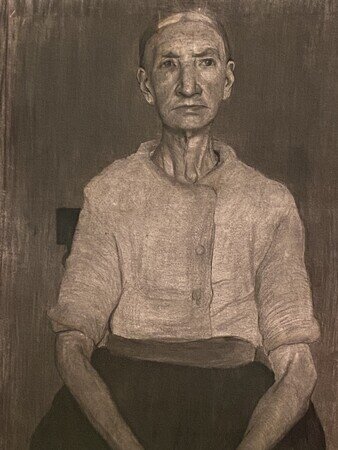

Farmer's Wife, 1899, detail.

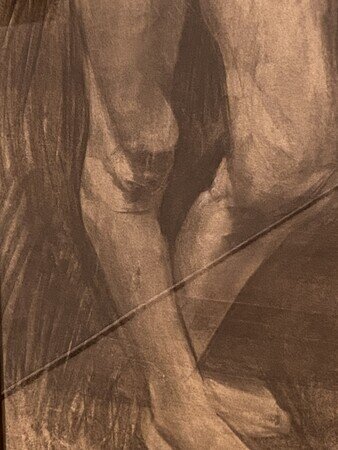

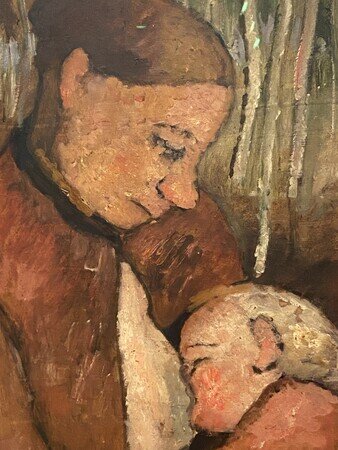

These drawings are very detailed, highly realistic, very defined noses, arthritic hands, unique bone structure of a certain girl’s legs. Where does this detail go in the paintings more often reproduced and known?

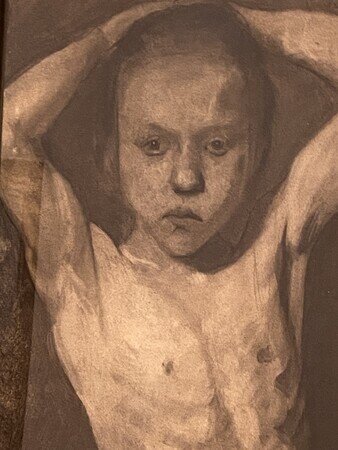

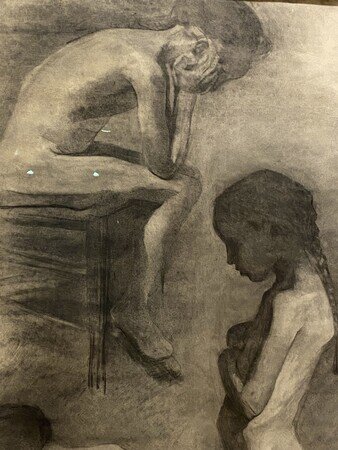

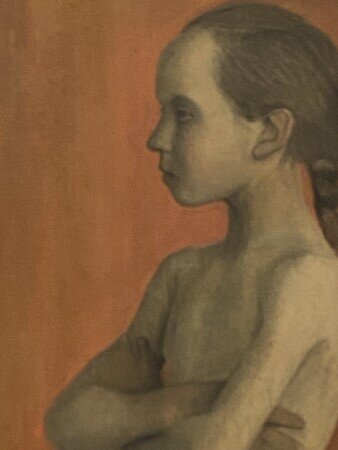

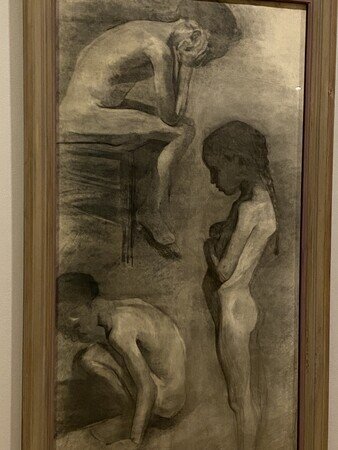

Standing Nude Girl with Arms Crossed Behind Her Head, 1899-1900, details.

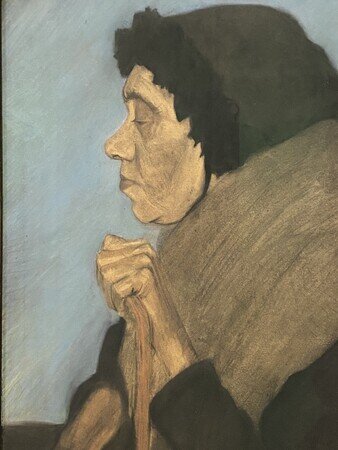

The charcoal portraits are at once very impoverished looking, people worn by life and reduced, and, very large, at least life size, monumental, a word often used to describe Modersohn-Becker’s work. Some with pastel over the charcoal are backed by a single color, especially a blue, that makes me think of portraits of royalty I used to visit at the Louvre, by Jean and François Clouet, or those enameled miniatures. A striving for the significance of this particular figure.

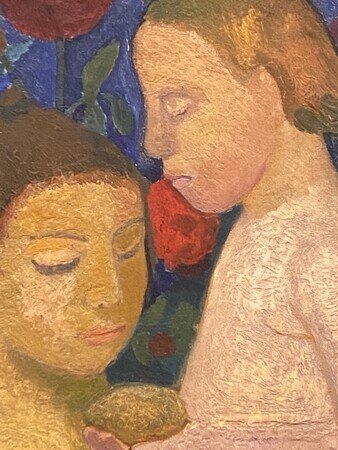

Old Woman in Left Profile Holding a Stick, 1898-1899, detail photo, Arp Museum

3. I go to sit in the second half of the exhibition, a bench where I can make notes. I am not photographing yet, trying just to use my eyes, look. Casting my eyes about, these more symbolic paintings, I am overwhelmed by the impression of Gauguin. These look so deliberately like Gauguin to me. Walking around, I find that indeed Modersohn-Becker was taken with Gauguin in Paris when she was studying and working there.

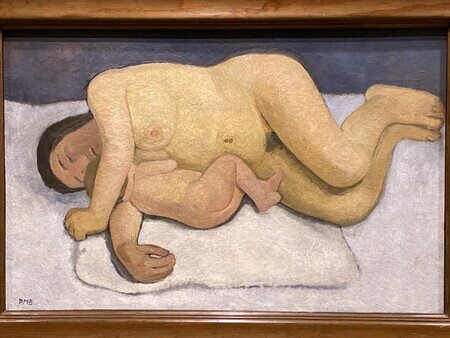

Sleeping Child, 1904, detail.

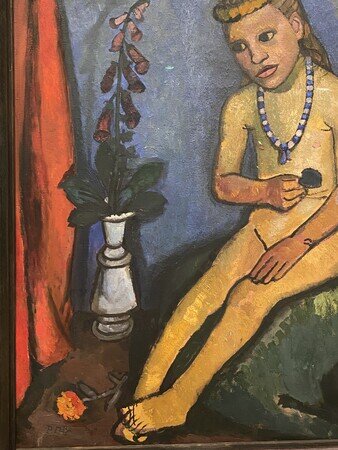

Nude Girl with Flower Vases, 1906-7, detail.

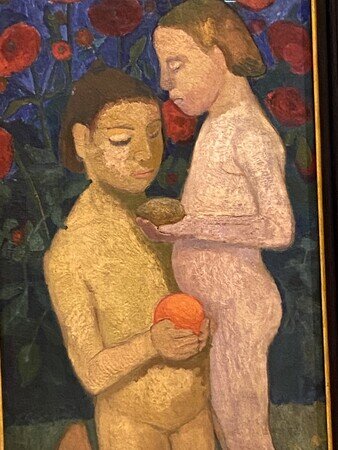

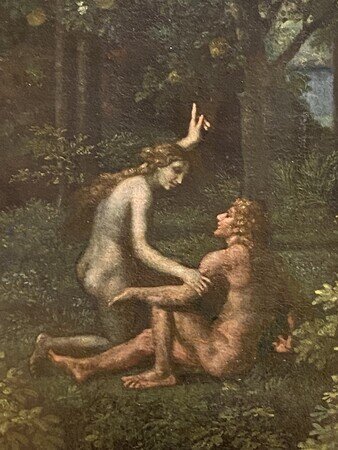

4. I am beginning to get somewhere. I listen through a complete round of the video of the woman scholar talking about Modersohn-Becker and her life that has been placed running in a continuous loop in the center of the passage that links the two main rooms of the exhibition. I listen with interest, then boredom, then, the third loop, fearsome irritation. I go to look at the Gauguin paintings with my hands over my ears, like a child when a fire engine passes, fiercely clamping my ears and listening to the rush of my own blood, paintings of women, children, children and women, stripped to their nudity and their symbolic meaning, with offerings, flowers, fruit. A girl kneeling with another standing close before her.

Standing and Kneeling Nude Girls in Front of Poppies, II, 1906, detail.

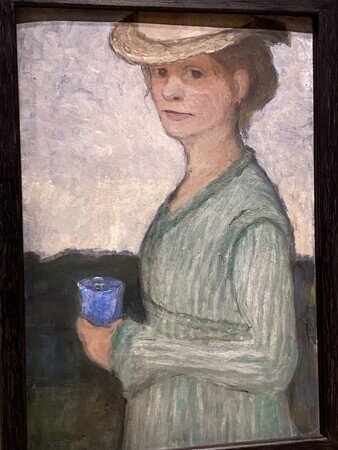

5. Why did she want the people to feel symbolic like this? This was happening, in France and Germany. Like Beckmann before Beckmann. Like the kind of symbolist portraits that Berthe Morisot had begun to do in the years before her sudden death. Have never really gotten that.

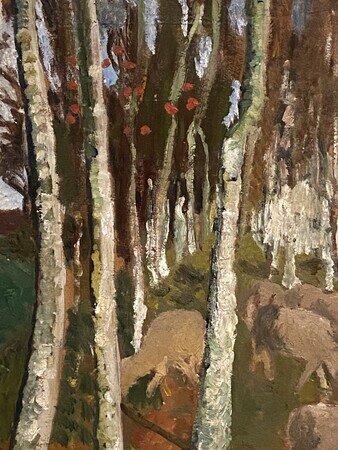

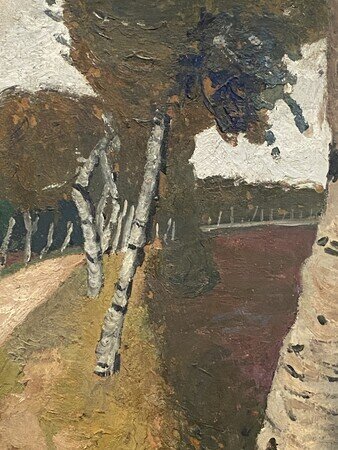

6. Birch trees. About a quarter of the second part of the exhibition is of portraits of children and women with birch trees behind and around them, or of landscapes that are just of birch trees.

Birch trees, I think, are material, paper, peeling off of them. Would appeal to painters. I know I’ve thought of them as writers’ trees, love them for their paper myself. White patchy areas with scroll, dark edges around the patches.

They frame these portraits.

Also, they recede. Lines of them going back along the edges of roads, fields.

Recession is part of the large drawings, I remember.

7. Back to the large drawings. This time they look like August Sander. Catalogue of working people. Assertion of significance. Side profile.

Three Nude Girls, 1898-99

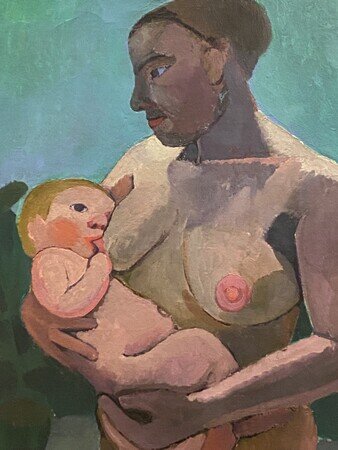

8. I begin to photograph details, with the first self-portrait, the one where I saw the edges, and the large nude mother nursing the child. Many of the visitors to the exhibition are women, one older woman says to a younger, possibly her daughter, grown, both adults, “I remember those days.” And the adult daughter, “but you weren’t nude.”

9. As I am photographing these difficult subjects, the women around me converse, they stand in front of a girl with her arms firmly crossed, one woman notes to another, “I am standing in just the pose she is standing in.” Several repeat to each other the information in the opening wall text, that Modersohn-Becker, after a complex interior back and forth about whether to paint or have children, attempting both, dies two weeks after giving birth, of an embolism. The word “embolism,” is repeated from one woman to another.

10. Through the passageway, the voice of the scholar is no longer killing me, has someone turned its volume down. I photograph the paintings of symbolic children. The child kneeling, the other standing, that is Poussin, it is the original garden, the figures almost too close to one another, as in that painting. It comes into my mind, complete, the phrase, “she was scavenging the Louvre.”

Nicolas Poussin, Spring (The Earthly Paradise) in The Four Seasons, 1660-1664, Louvre, detail

11. Then, photographing all the children and women among the birch trees, this mottled skin I had been noticing. Her way of painting thin patches, almost like scales of rosy skin. Birchbark. And in one of the wall texts a note that, like many, Modersohn-Becker associated the slender birch trees with wood spirits, that she believed both in Christian meanings, and in a paganist system of the kind that many among the artists and writers she knew were interested in in this period of modernization.

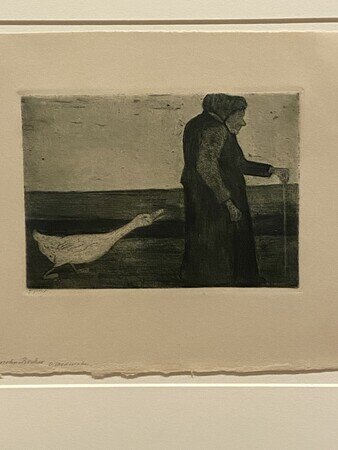

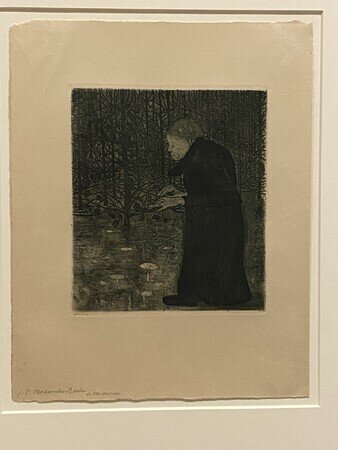

12. Sitting on the bench again, I write down “scavenging the Louvre,” and also think about what she would have lived through, had she lived. The first war was coming. And she could well have survived through the second, she would then have been only sixty at the end of World War II. She would have been courageous, I think, would have known it all for what it was. Expressionism, Surrealism, total abstraction. She could have led and followed. My camera is running out of battery and my mind of attention. I think I can get back once more before the show closes, but I have made a start with Modersohn-Becker. I photograph, last, five etchings, small, done with black ink on paper in 1899, perhaps these are a unification of the large black charcoal portraits, the later symbolic paintings, ‘Seated Old Woman' ‘Woman with Goose,' 'Blind Woman in the Forest.'

I am leaving, this self-portrait, with a lemon, 1906-7