Summer of Cezanne

Thursday, September 8, 2022

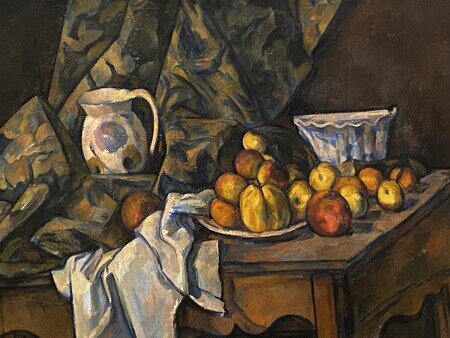

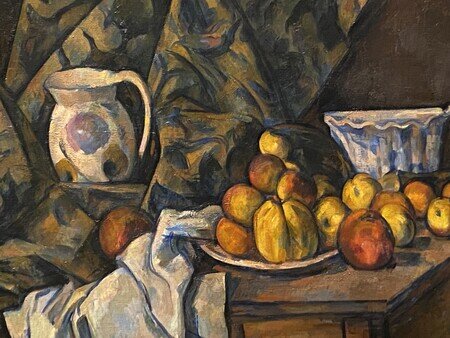

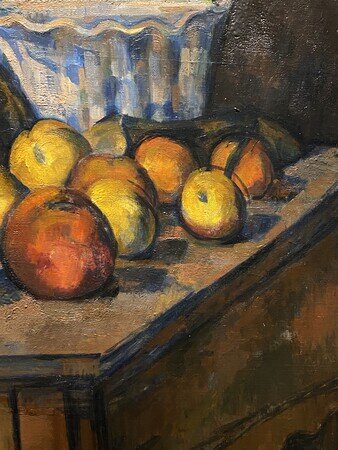

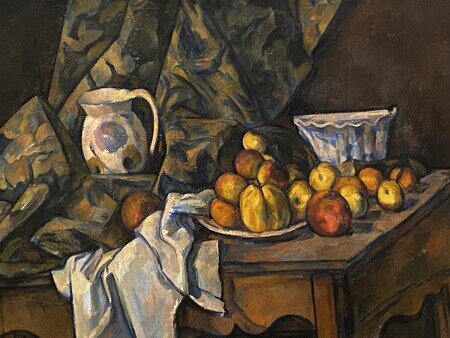

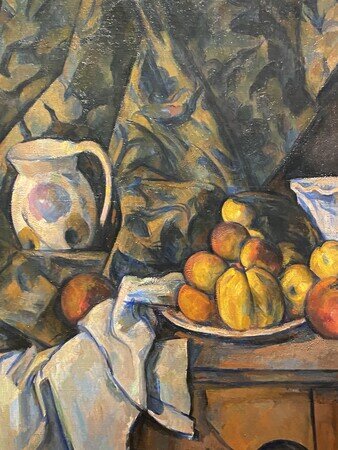

Paul Cezanne, Still Life with Apples and Peaches, around 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, photo Rachel Cohen

The summer of Cezanne is over. It was a beautiful season, marked by voyage, worry, discovery, growth, and, near to us and to those we know, by illness, flood, fire. The children had bikes, lakes and ponds were blue, we ate corn that had grown well and corn that hadn’t. I went, ten times, to the Art Institute here in Chicago and studied the Cezannes, more than a hundred of them, assembled probably for the last time in my lifetime, in a show at once magnificent and calm.

I’ve written a review of the show for Apollo Magazine (if you subscribe, it's here), and tried to say, as best as I can, how the show was built by its curators – Caitlin Haskell, Gloria Groom, and, at the Tate, where the show will soon open, Natalia Sidlina. Here, though, I’d like to make a first pass at writing about a certain painting, looking at it over and over, in density and close proximity, with repetitive dedication.

Cezanne painted Still Life with Apples and Peaches around 1905. It is now housed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. It’s a still life in the later late style, which I hadn’t, until this summer, even realized was a whole separate style during the last five or six years of Cezanne’s life. His palette went to maroon, orange, ochre, yellow, some pine greens and oaken wood colors, grays, and a few quite bright magentas, aquas and blues.

The painting, a horizontal rectangle, has a long fold of dark cloth that descends from the wide top center and flows out to the left.

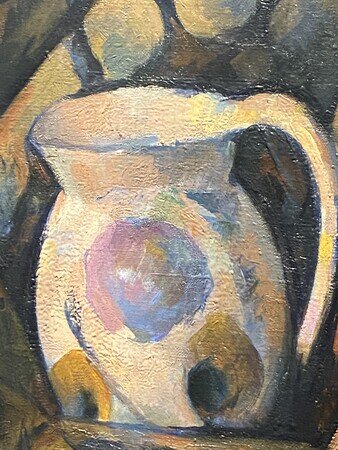

Settled within this flow is a white pitcher that has three round shapes, one blue-lavender and two like the yellow eyes of peacock feathers.

There is a table which is evidently in two completely different halves, the small part visible on the left side of the painting is significantly lower than that holding up the items on the right side of the painting.

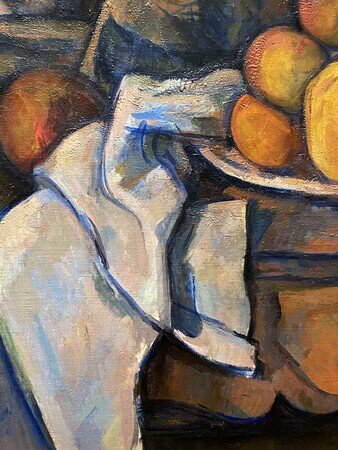

A second cloth, of an extremely bright white with blues and pinks painted throughout it, is like a waterfall over the front of the table, over what would be the seam of this impossible division.

On the right, elevated half of the table stands a bright white bowl, also with blues intermingled, a plate with a pyramid of orange, red, and especially yellow fruits, and then another seven or so fruits that are directly on the table.

The back right background is of deep brown with something of maroon in it.

I had noticed Still Life with Apples and Peaches the first time I went through the show, and had glanced at it again on my second visit, which was a chaotic one with in-laws and children. Then, on my third visit, I had the chance to walk through the exhibition in empty silence with the curators and conservators and a few other guests. I asked Caitlin Haskell if anything had surprised her when it came out of the crate. She pointed this painting out as one they had had to decide where to hang. They had considered the end wall of that still life section, “I thought you’re not going to get a better painting than that,” but in the end had decided on the middle of the long wall.

With the help of the curators, and the other visitors there that day, including the artist Julia Fish, I began to see the unity of the second half of the show coalescing around this very late period, from 1900-1906. This was an impression that grew stronger with each visit I made. In introducing this late late period, Still Life with Apples and Peaches was a pivot point, and a point of contemplation, like a promontory out over the valley from which you could see the rest unfolding.

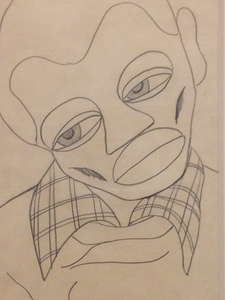

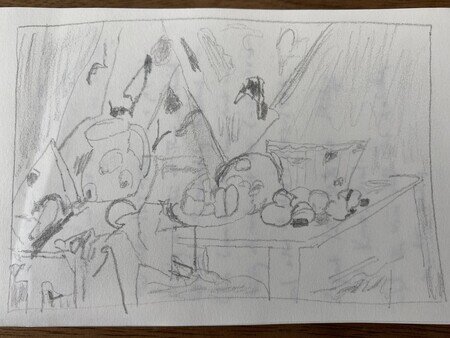

On my fourth visit to the show, I sat a long while with Still Life with Apples and Peaches, and drew it fairly carefully, another way of learning its relationships.

Drawing showed me the downward point in a triangular back section of the cloth, and the way this intersected with a kind of dark dome behind the pyramid of fruits.

In the dome, if you look closely, you can see, darkly, the fruits again, in shadow or reflection.

On my last visit to the show, in August, I sat half an hour with Still Life with Apples and Peaches. There would be a great deal to say of what I felt in that experience of late looking, but I think it is still too interior for me to write it. Instead, I will write another true thing. After I had been looking for twenty minutes or so, and had taken a last round of pictures, an elderly couple sat down on the bench with me, and after a little while, they asked me what I was looking at in the painting – they seemed like they, too, were really involved with the painting, so I told them some things I had noticed.

The bright whiteness of three elements: the pitcher, the dish at the back right, and the white cloth.

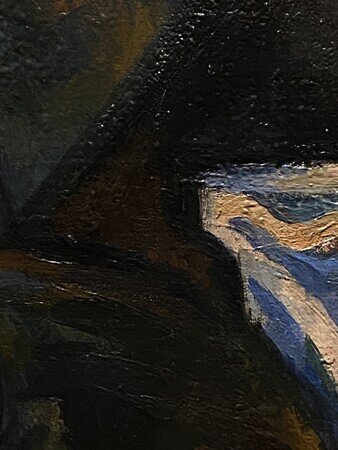

Especially prominent in the cloth is a tall patch of light purple-blue-aqua with a tall diagonal edge that might be the place in the painting that comes the furthest forward. From this I looked back to the pitcher, and gradually became interested in how the handle disappears at its lowest point into an area of very deep darkness.

The emergent diagonal – from the dark shadow patch to the bright cloth patch came to seem like an important axis of the painting.

I had spent some more time looking at the fruit on the right hand side of the table.

And when I came back to the jug it was much clearer to me that the jug was almost like a building on a small island within the river of darker cloth, and that it was even reflected in that darker cloth, where you can see pattens very like the low peacock-feather-eyes in the cloth.

This was what I spoke with them about. They were interested, and we talked of painting for a little while, and shows they had seen in Paris, and how they loved a particular unfinished Cezanne where you could really see him building the picture up from the back, stroke by stroke. I stood up. I told them I was sorry I couldn’t stay, but that I had to go pick up our child.

It is September now, the summer of Cezanne is over. I go on thinking about my last visit with this painting. Some Cezannes will, after time, whirl, but Still Life with Apples and Peaches did not seem to me one of those. Its movement is about flow. It is riverine, and its objects – the pitcher and the fruits – stand still within the flow of cloth.