Winter Gardening Pissarro

Friday, January 22, 2021

Photo Rachel Cohen

Yesterday it went up to 39 degrees in Chicago, which is warm right now in January, and it was a lovely day, sunny and quiet. Looking ahead to many cold days, I had seen this one on the horizon and planned to use it for a pleasant task in the garden, cutting the dry Northern sea oats. These are beautiful grasses with very lovely seeds in a pattern like a short bit of wheat. They are already in profusion in our garden, and the dry stalks need to be cut in January or the seeds are too successful and take over the garden.

There was snow on the ground, a little less than an inch, enough that my boots left clear prints, a glittering soft snow that had fallen the day before but kept its whiteness, and this added to the sense of warmth and good cheer. It is a small urban garden, that seems bigger than it is because it was densely planted by the previous owner; you are never far from the house or the alley that runs behind the garden.

Yesterday, many workmen were out doing different projects and had parked along the alley, there were sounds of chopping and grinding. On the other side of the fence from me, there was a pick-up truck parked, perhaps twenty feet from where I worked, and three men were gathered near it, talking and laughing. I was a little uneasy without my mask, and I was also glad to hear people.

Our daughter had used her fifteen-minute break from online school to come out with me, but now she was back inside at her computer, and I was just cutting the grasses.

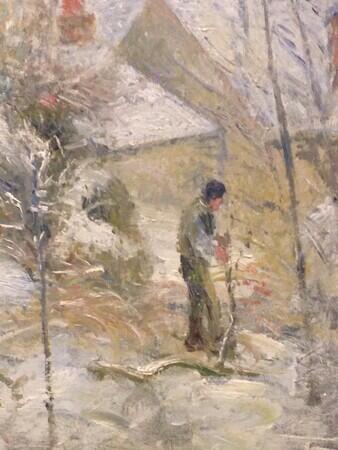

What came to mind was a winter Pissarro. Rabbit Warren at Pontoise, Snow, 1879. I looked at it again during the brief months when the Art Institute was open – I’ve loved it and I loved it again.

Camille Pissarro, Rabbit Warren at Pontoise, Snow, 1879, The Art Institute of Chicago. All detail photos Rachel Cohen.

You bend a hand-full of grasses and you cut them a few inches above the base. An ordinary garden clippers will cut about ten stems at a time. You try not to let too many seeds fall on the snow, but seeds fall on the snow. And look beautiful.

The Pissarro is of a man standing, on some kind of hillock, in the snow, and he is proportioned small – it is the landscape around him that matters, although he matters, too.

He was a fine man, Pissarro. He worked very hard all his life, never had quite enough, loved his large family, was Jewish, radical, Danish-French-Carribbean, born on the island of St. Thomas which was then the Danish West Indies, he was for Dreyfus, he was Cézanne’s treasured teacher, he had a long beard, and he painted with his own genius.

In the winter garden, cutting dry Northern sea oats, I thought of this landscape, and drew strength.

Yesterday, I had a message from a colleague at the Art Institute. Times are hard there, the museum has closed again and many people have been furloughed. The AIC workers have set up a mutual aid society. Many kinds of aid can be given and received at this website, and you can donate money to the group here, which I did this morning, a colder day, 14 when we got up and began to ready ourselves.

1879 was an especially severe winter, and Pissarro was one of the great snow painters. But it wasn’t the snow in Rabbit Warren at Pontoise, Snow that brought the painting to mind, it was the sense of the thin lines of dry brush around the figure, the sense of his activity even as he holds still. In winter things are so near to death and, restrained, so active. A handful of thin lines, dry stems.

* * *

I find now that I have already written about Rabbit Warren, Pontoise in this notebook -- last April, the last snow of last winter. "Pissarro. Out of Season." When I wrote about it then, I said that I had thought to save this painting to write about later, I had expected to write about it in this winter, the winter of 2021, and that it was hard to imagine what that winter would be, and that I was writing of it in April because it had snowed. I had forgotten this when I thought of the painting, wrote of it again. So here are two moments of this pandemic year with Pisssarro -- one from an unexpectedly snowy day in April of 2020, another from an unexpectedly warm day in January, 2021, mutually reflective.

* * *

Often for these notebook pieces, I write a little dedication line at the end. While I was working in the garden, a few people came to mind. One was Richard Brettell, art historian, curator and museum director, whom I met once, and whose books on Pissarro matter very much to me. I wrote the dedication, and, imagining that I would send him a note, searched for him and found that he died of cancer in July of this past year.

Richard Brettell was a curator of European paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1980s, and so he would have known this painting well. When I have had time to think about his work and to revisit in mind the hour I spent talking with him, I will try to write about that.

The news of his death seemed to have come through the dried grasses, the sense of the painting. But his death was not what I set out to write about. I set out to tell you that yesterday it was 39 degrees in Chicago, it was sunny, there was snow around the sea oats, three men talked in the alley near a truck, and that the scene made me think of Pissarro.

For friends and colleagues, studying Pissarro, carrying paintings outside of museums, working in gardens – the late Richard Brettell, Nancy Chen, Melissa Seley, Lawrence Weschler.