Pissarro in March, in memory of Richard Brettell

Sunday, March 21, 2021

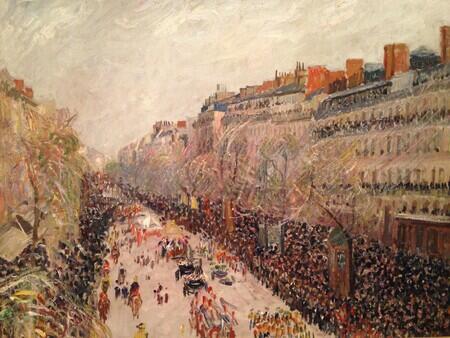

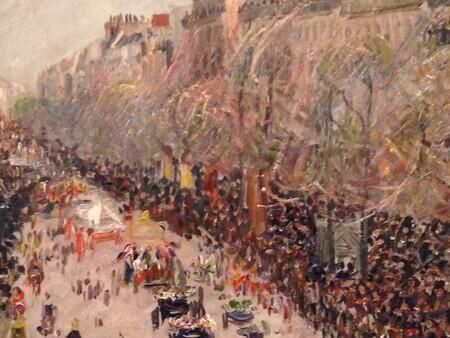

Camille Pissarro, Mardi Gras on the Boulevards, 1897. Fogg Museum of Art / Harvard Art Museums. All photos Rachel Cohen.

In 1897, Shrove Tuesday fell in March, and, in Paris, the annual Mardi Gras parade came down the Boulevard Montmartre on a blustery day. At a window overlooking the Boulevard, Camille Pissarro waited, brushes at the ready. The previous month, in February, he had begun an ambitious project, which would result in sixteen paintings of the Boulevard Montmartre, showing winter giving way to spring. Pissarro painted in the mornings, the afternoons, and the evenings; he painted in snow, rain, and the rare sunshine; he painted grey, and, when it came at last, he painted green. And he painted people – hailing cabs, rushing down the street, pausing to talk, cleaning, shopping, loitering.

Three of the sixteen canvases in the series of the Boulevard Montmartre show the parade crowd from that Shrove Tuesday. In the first, there is a thick column of organized marchers, the second also has a very large volume of people filling the street, and this last one, which belongs to the Harvard Art Museums, seems later in the day, when the people were more scattered about, the onlookers fill the sidewalks, the trees were festooned with confetti, and afternoon brightness could be discerned in certain pinks. I saw it at what I still think of as the Fogg Museum while we still lived in Cambridge, probably in 2015. I was already very interested in Pissarro; I was only beginning to realize how interested.

A little before that, in the summer of 2014, I had given a talk at Edith Wharton’s house, The Mount, and at the dinner after the talk met the director of the Robert Sterling Clark Museum. I told him that I was working on a project about painting and time and Impressionism, and he said I should come and talk to Richard Brettell, who was in residence at the Clark that season, and he set it up for me. We were only out in the Berkshires briefly, and the next day we went to the Clark, and looked at a few paintings, and I was admitted to the research area, and sat at a long table with Richard Brettell, notebook out, and I asked him cloudy questions about time and Impressionism and he answered briskly and with seeming enjoyment. Though I did not know his work then, I at least had the good sense to say that this was all in formation and a happy opportunity offered by the museum’s director and his good will. He told me to read Arnold Hauser’s The Social History of Art, which I subsequently did, and found very helpful. Somewhere I must have the rest of my notes from the conversation.

Later, I bought the catalogue of a profound show that Brettell co-curated at the Dallas Museum of Art, with the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Royal Academy in London, called The Impressionist in the City: Pissarro’s Series Paintings. The only time that Pissarro’s great series paintings from the city, more than 300 canvases in 11 series, have been seen together. Not even in his lifetime were they so exhibited. The show was in 1992-93; I was in college, knew nothing of such things. The painting I would later see at the Fogg, Shrove Tuesday, Boulevard Montmartre, was presented. They were able to assemble twelve of the sixteen works from the series. Paging through the catalogue this morning, I felt MARCH. I felt the trudging grey of February give way to the wet windiness of March, felt the people eating their last feast and going out into the streets for the complicated celebration of their coming atonement, felt the thinning out of Lent and March, which is not our religion, Pissarro and I are both Jewish, but is one accompaniment of this season, one interpretation of this season.

This morning I looked around all the bookshelves in the house until I located another book I had found, after meeting Brettell, a catalogue for a show called Pissarro’s People, 2001, which he wrote the text for. I bought it in anticipation of a future when I would learn more. I think it is probably a great book on Pissarro, the culmination of many decades of study. I just tore the plastic wrap off this morning.

Knowledge is so fleeting. The thin crackle of the plastic wrap between my dry garden-hardened fingers, and as I crumpled it up to throw it away, I had the illusion that that was the meeting, the rich hour and exchange of few emails from the summer of 2014, crinkled up and fleeting away.

Richard Brettell died in July of 2020, of cancer, at the age of 71. I learned of his passing earlier this winter. I go on learning about Pissarro.