Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin, Notes of Native Sons

Wednesday, June 3, 2020

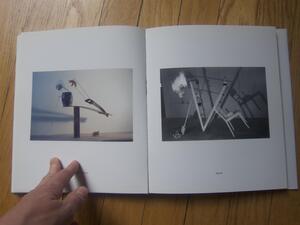

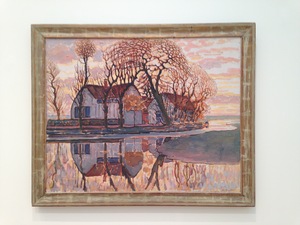

Beauford Delaney, Untitled (Village Street), 1948. Terra Foundation of Art. All detail photographs Rachel Cohen.

Between the thirties and the end of World War II, there was perhaps as radical a change in the psychological perspective of the Negro American toward America as there was between the Emancipation and 1930.

When I looked at this painting, painted in 1948, Beauford Delaney’s Untitled (Village Street) at length this winter, I was very struck by the way one side of the painting is very clearly in color, and the other very clearly emphasizes black and white. The color division is so evident that you have to think about it.

I do not think it is clear what you have to think, though. You might think that is a kind of commentary on the way that black and white are invented, and that the world is actually enormous varieties of color. You might think that it is a thought about imposed divisions, or about the way political lines are drawn on city streets. Or you might not.

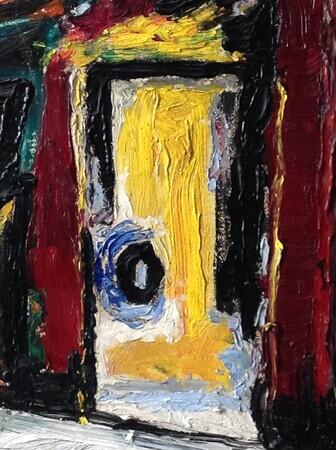

The group of lines which are most obviously evocative of a figure are a part of the black and white territory, but also have a lot of yellow around them, which was Delaney’s most significant color, and one he often used in conjunction with light and inner light.

I saw the painting, which belongs to the Terra Foundation, in the basement storage of the Art Institute of Chicago. It was hung down fairly low and I had to sit on the ground to see it, and to photograph it. It was also lit from the side by a conservation lamp, which allows the depth of the paint and the shadows cast by the paint itself to be discernible in the photographs.

**

Yesterday morning I reread James Baldwin’s essay “Notes of a Native Son.” You will remember that one of the things it circles around is the death of his father in 1943. Between the day of Baldwin’s father’s funeral, and the day of driving his father to be buried, an insurrection broke out in Harlem.

“Notes of a Native Son” is partly about the different feelings in the streets that James Baldwin, in the heightened state of grief, tension, war, outburst, was able to discern, and, later, to write about. The essay “Notes of a Native Son,” was published twelve years later, first as an essay in a magazine, then in the book of the same title, both in 1955.

There has been a lot of historical analogizing lately, and I, too, have been trying to figure out what is happening in 2020 by considering the flu of 1918, the Great Depression, the events of 1968. Because I read Baraka’s Blues People a few weeks ago, and because I wanted to think about Beauford Delaney’s 1948 painting, Untitled (Village Street), I’ve turned to the 1940s with a different attention.

In the 1940s, James Baldwin and Beauford Delaney were close friends – sometimes like a father and a son, sometimes like a mentor and a student, sometimes with the closeness of lovers, though they were not lovers, at different times one was the caretaker of the other, they were always artist-friends. They formed ideas together, about many things, about city streets, reflection, about being a Black man and a queer man on a city street in the midst of a World War and a very difficult period of racial strife.

**

I had the idea of setting some quotations from “Notes of a Native Son” next to Beauford Delaney’s Untitled (Village Street) of 1948 that I began considering here on Monday, and which I am thinking about this week, partly as a way of remaining aware through all the parts of my life of the courage of protestors right now.

Yesterday, I was unable to complete this set of reflections with the time they required. I also wanted to honor the day of reflection that many were observing yesterday by not posting. I found on reading through “Notes of a Native Son” that I really just wanted to quote the whole thing. So there is a link to a pdf of it here and at the end of this essay. Baldwin's essay is a reflection partly about losing a parent in the midst of pandemonium, and about the 1943 insurrection in Harlem. It is a deep experience to read it now.

If you are still here, then I will say a few things about Baldwin and Delaney’s relationship and the Delaney painting. Then I have put some passages from the Baldwin essay, and especially about what the streets looked like after looting. And this let me think a bit about meanings of abstraction and jaggedness, and perhaps you will find that idea is worth something if you get to it.

**

Baldwin had first met Delaney in 1940, when Baldwin was fifteen. He began spending quite a bit of time with Delaney in the Village, which was a different set of streets than the ones in Harlem where Baldwin had been raised, more Bohemian, less confined and restricted in racial terms.

Toward the end of his life, in the 1985 essay “The Price of the Ticket,” Baldwin wrote about what it meant to him to first go through the door of Delaney’s studio, and to meet a Black man who was an artist, “Beauford was the first walking, living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist.” They walked the streets of the Village together, Baldwin learning from Delaney, and Delaney from Baldwin, and Delaney told Baldwin to look at the puddles, the oil in the city puddles, the way the colors refracted the city streets.

In “The Price of the Ticket,” Baldwin circled back to 1943 and its conjunction of different griefs and transformations, “When my father died, Beauford helped me to bury him and I then moved down to the Village.”

Part of what I am asking myself and my images of this painting today is, does this untitled landscape, which parenthetically states a location in the Village, Greenwich Village, also carry Baldwin’s memories of the streets of Harlem, as they were at different times, including the time of the insurrection?

**

Baldwin published one of his earliest essays “The Harlem Ghetto” in February of 1948, presumably before this painting was finished, perhaps even before it was begun. So that Delaney would obviously have had Baldwin’s ideas about city streets in his head as he worked.

“The Harlem Ghetto” is unlike the first published essay by any other writer in history. Still, it is profound to then read “Notes of a Native Son,” and to see the writer Baldwin had made himself into by 1955.

And, or, also, did this painted streetscape, or even the potential of this streetscape, help to conserve or transform for Baldwin something of his own understanding that he would carry with him when he went abroad to France later in 1948 to go on becoming the writer he became, who would look back and write “Notes of a Native Son”?

**

Notes of a Native Son opens:

On the 29th of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born. Over a month before this, while all our energies were concentrated in waiting for these events, there had been, in Detroit, one of the bloodiest race riots of the century. A few hours after my father’s funeral, while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel, a race riot broke out in Harlem. On the morning of the 3rd of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.

The second section begins:

I had returned home around the second week in June—in great haste because it seemed that my father’s death and my mother’s confinement were both but a matter of hours….

All of Harlem, indeed, seemed to be infected by waiting. I had never before known it to be so violently still. Racial tensions through this country were exacerbated during the early years of the war, partly because the labor market brought together hundreds of thousands of ill-prepared people and partly because Negro soldiers, regardless of where they were born, received their military training in the south. What happened in defense plants and army camps had repercussions, naturally, in every Negro ghetto. The situation in Harlem had grown bad enough for clergymen, policemen, educators, politicians, and social workers to assert in one breath that there was no “crime wave” and to offer, in the very next breath, suggestions as to how to combat it. These suggestions always seemed to involve playgrounds, despite the fact that racial skirmishes were occurring in the playgrounds, too. Playground or not, crime wave or not, the Harlem police force had been augmented in March, and the unrest grew—perhaps, in fact, partly as a result of the ghetto’s instinctive hatred of policemen….

I had never before been so aware of policemen, on foot, on horseback, on corners, everywhere, always two by two. Nor had I ever been so aware of small knots of people. They were on stoops and on corners and in doorways, and what was striking about them, I think, was that they did not seem to be talking….Another thing that was striking was the unexpected diversity of these groups…. Seventh Day Adventists and Methodists and Spiritualists seemed to be hobnobbing with Holyrollers and they were, alike entangled with the most flagrant disbelievers; something heavy in their stance seemed to indicate that they had all, incredibly, seen a common vision, and on each face there seemed to be the same strange, bitter shadow.

The churchly women and the matter-of-fact, no-nonsense men had children in the Army. The sleazy girls they talked to had lovers there, the sharpies and the “race” men had friends and brothers there. It would have demanded an unquestioning patriotism, happily as uncommon in this country as it is undesirable, for these people not to have been disturbed by the bitter letters they received, by the newspaper stories they read, not to have been enraged by the posters, then to be found all over New York, which described the Japanese as “yellow-bellied Japs.” …. [E]verybody felt a directionless, hopeless bitterness, as well as that panic which can scarcely be suppressed when one knows that a human being one loves is beyond one’s reach, and in danger. This helplessness and this gnawing uneasiness does something, at length, to even the toughest mnind. Perhaps the best way to sum all this up is to say that the people I knew felt, mainly, a peculiar kind of relief when they knew that their boys were being shipped out of the south, to do battle overseas. It was, perhaps, like feeling that the most dangerous part of a dangerous journey had been passed and that now, even if death should come, it would come with honor and without the complicity of their countrymen. Such a death would be, in short, a fact with which one could hope to live….

I am thinking, reading along here, that communities of color, and all thinking newspaper-readers, have been well aware for nearly three months, that people of color and workers whose jobs are not primarily at computers, are being asked to be “soldiers” on the “front lines,” to deliver the mail, the groceries, the factory-produced meat, the health care, the child care, the economy – and that at the same time these same people knew they were going to be left to die by their government and their employers, who could not be bothered to find them decent protective equipment or to get in place the testing and public health protocols and the economic support that might save their lives. That they had, in fact, been left to die for the last forty years and the last four hundred years and that the infrastructure had been deliberately misbuilt for all that time. And that backing all this up would be the systematic abuse of Black and Brown people by the police.

I also felt very connected, as I imagine many people do right now to “that panic which can scarcely be suppressed when one knows that a human being one loves is beyond one’s reach, and in danger.” And when that danger – both the danger people I love face through the epidemic and the danger people I love face in continuing to protest – is the direct result of an authoritarian government’s systematic negligence and misguided use of force.

**

I want to include Baldwin’s description of the streets on the morning they drove his father to be buried with the money that Beauford Delaney had gotten to pay for the burial. But the description comes close to the end of the essay, and is full of considerations that become obscure without the rest of the essay, in parts of which Baldwin has been reflecting on his own struggles, internal and external, with violence, and the struggles he and his father have had with hatred and with pain. So that there is not a sharp judgment that might be taken from these lines when they are quoted and especially when they are quoted by me, a Jewish woman who has been living for a few years in a well-off part of the South Side of Chicago.

Along each of these avenues, and along each major side street—116th, 125th, 135th, and so on—bars, stores, pawnshops, restaurants, even little luncheonettes had been smashed open and entered and looted—looted, it might be added, with more haste than efficiency. The shelves really looked as though a bomb had struck them. Cans of beans and soup and dog food, along with toilet paper, corn flakes, sardines, and milk tumbled every which way, and abandoned cash registers and cases of beer leaned crazily out of the splintered windows and were strewn along the avenues. Sheets, blankets, and clothing of every description formed a kind of path, as though people had dropped them while running. I truly had not realized that Harlem had so many stores until I saw them all smashed open; the first time the word wealth ever entered my mind in relation to Harlem was when I saw it scattered in the streets. But one’s first, incongruous impression of plenty was countered immediately by an impression of waste. None of this was doing anybody any good. It would have been better to have left the plate glass as it had been and the goods lying in the stores.

It would have been better, but it would also have been intolerable, for Harlem had needed something to smash.

Part of what has caught my attention in these days is the way that the city streets carried, for Baldwin, the abstract understandings of the people who lived near those streets, reflections on the meanings of their lives, on the situation of their country, and on objects themselves, what kind of value they should have, how they could or should be splintered, shattered, made jagged and broken. I want to add that I am not aestheticizing violence and destruction, or arguing for violence or destruction, I am thinking that street jaggedness has significances that cannot be understood if one pretends that it has no abstract intentions, understanding, and meaning.

Amiri Baraka writes, brilliantly, about the kind of bebop music that emerged in the 1940s, and the meanings to be understood in the jaggedness and shatteredness of the sounds of Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, and Charlie Parker (whose portrait and music Delaney painted.)

Abstraction has been so deeply misunderstood. Like all good things, and like all things which may be good and may be bad and may be made to be profitable, it has been made the province of the wealthy, the white, the western, the first world, the male, the straight, the sane, the able, the scientist, the technology worker, the orderly, etc, etc, etc. But just look at abstraction in the hands of a person who was none of these things in any expected way:

**

Perhaps in the coming days I will see a way to quote the last few pages of Baldwin’s essay, but today I can’t see how to do it. It feels too much like taking a detail photograph of a place of reverence.