Constant Structure, Jennie C. Jones

Sunday, August 16, 2020

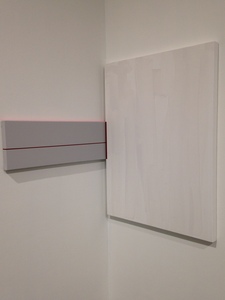

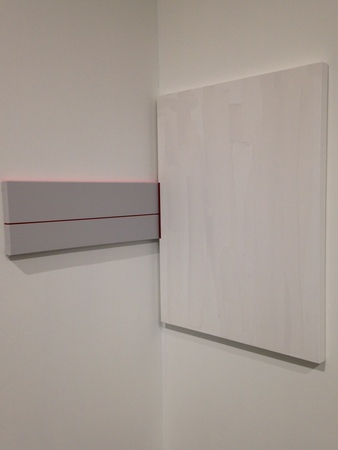

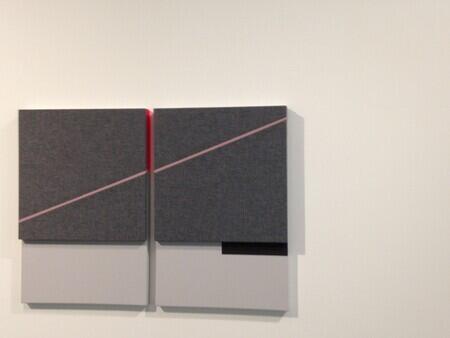

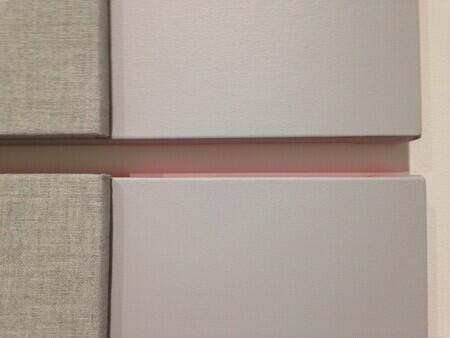

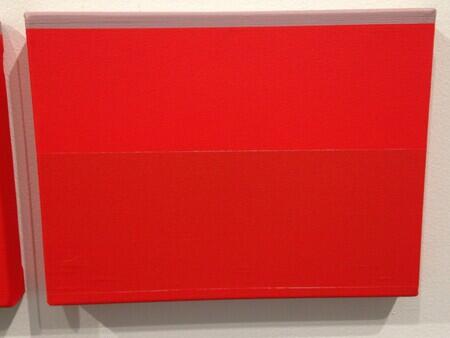

Jennie C. Jones, Corner Phrase / Soft Measure 2020. Acrylic on canvas 2 parts: 12 x 36; 48 x 36 in. All photos Rachel Cohen.

I have seen art.

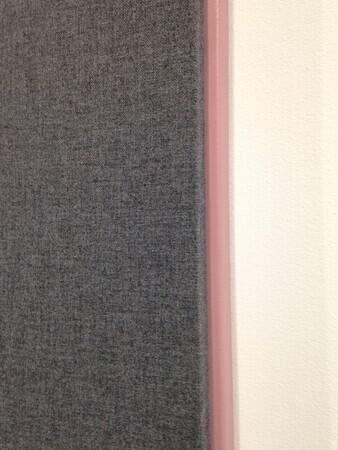

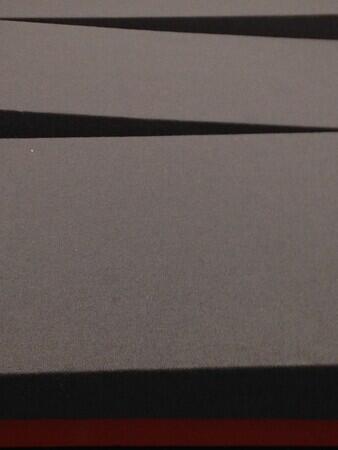

Detail, Corner Phrase / Soft Measure.

I have seen art. In person. Works of art, hanging on gallery walls, new works that I had never seen before.

For the first time in five and a half months.

I was extremely fortunate.

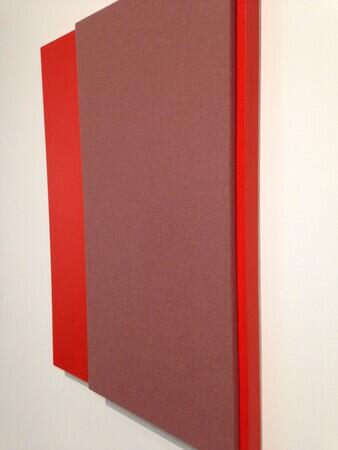

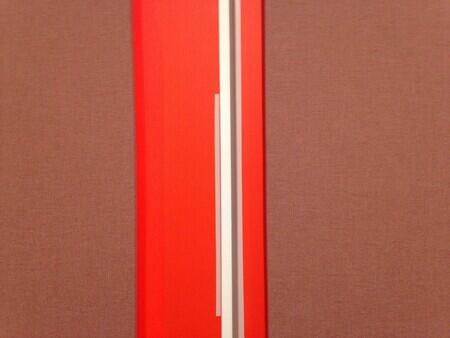

Detail, Vertical Shift, Fractured Crescendo.

The works were by Jennie C. Jones.

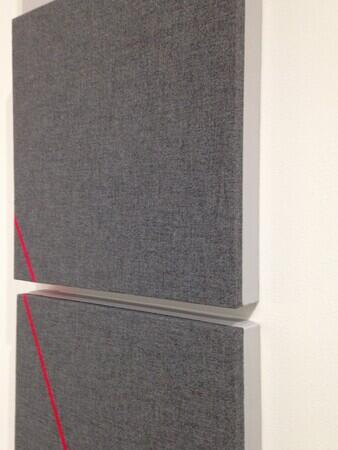

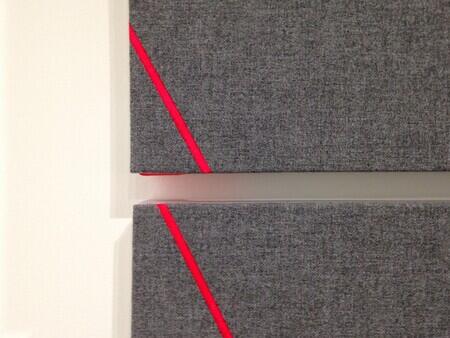

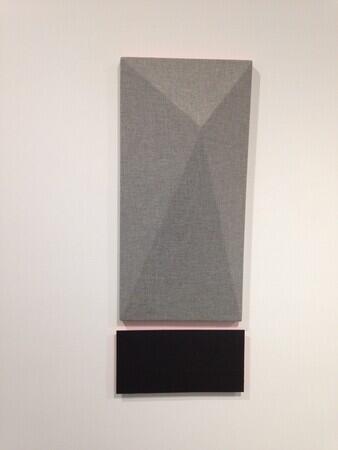

Fractured Crescendo, Rest, 2019. Acoustic panel, acrylic on canvas 2 parts: 49 1/2 x 36 x 3 inches overall.

Who works with minimalist ideas.

And ideas about sound, and about structures of music, which I am always trying to learn about.

I had seen a couple of her pieces a year ago in the Smart Museum of Art’s “Solidary and Solitary” exhibition, and had looked at them carefully with a friend who studies Black quietude. A good ground had been laid.

So, on Wednesday, it was that wonderful kind of augmentation where you begin from a place of interest and respect and then there is the sudden dizzying acceleration where you get to be with a body of work and its mastery.

**

I had come to the Arts Club of Chicago, my first venture into an unfamiliar building downtown, to sign some copies of my book for their members. I had gone immediately through to the outdoor patio where the books were set up. The gallery was empty, so that, although I had intended to go directly home again, on my way back through, I felt it was safe to stay and look. I began looking at the back.

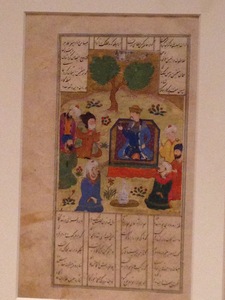

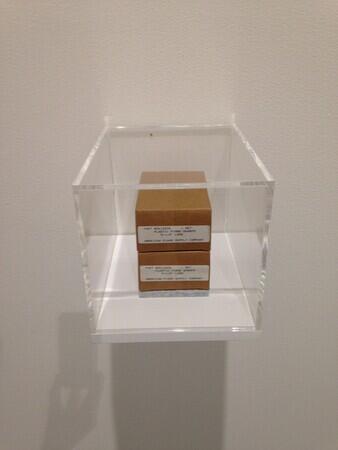

The first thing I photographed was this little work, displayed in a corner, of two boxes of plastic piano sharps.

Potential, Constant, Structure, 2020. Piano Keys in Original Boxes, Rubber and Felt. 2 parts: Each 4 x 6 in.,

encased in plexiglass box.

It was so knowing. It reminded me of works I love by William Pope.L that catch, who knows how this is done, all the skein of forces present in a commercial transaction, and make them transparent. I think it helped to start with something like the boxes that arrive in the mail at our house – the news from the world so often in commercial form.

Then I could go to look more closely at the small square and two large panels of Open Constellation (Oxide Red).

Open Constellation (Oxide Red) 2020. Acrylic on canvas; Acoustic panel, acrylic on canvas. 3 parts: 12 x 12; 36 x 48 in., (2 parts)

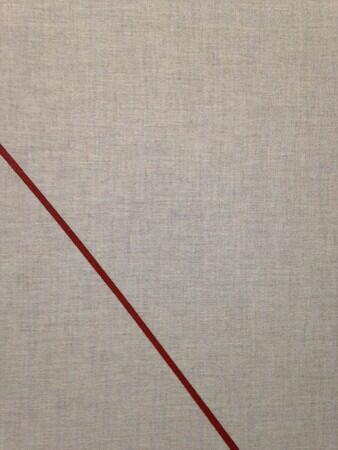

Detail, Open Constellation (Oxide Red)

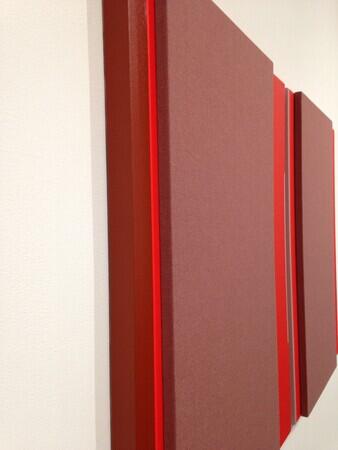

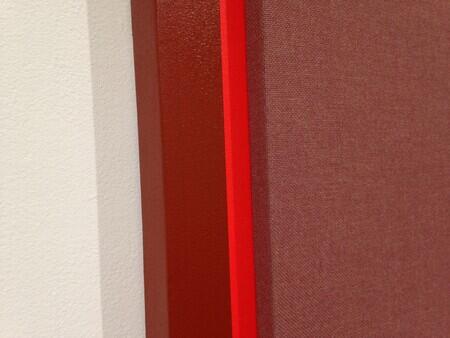

It was immediately apparent how much the artist is able to do with the space between two panels. Jones has often painted a bright or luminous color along the side edges of the panels, which casts a glow, or makes an interference, or draws the eye toward the back or around the side.

Detail, Open Constellation (Oxide Red).

Tears came in a matter-of-fact way. Not in the rare way they may come after long patience, with insight, but in a preliminary way, just as my part of first mutual recognition.

I was soon thinking that minimalism was exactly where to begin after five and a half months of deprivation. My senses were flooded but not overwhelmed.

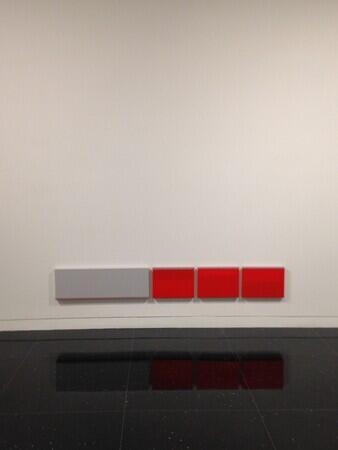

Unit Structures #1, Acoustic panel, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 x 3 in.

**

There have been many times in my life when minimalism has seemed a necessary quiet in the midst of the tumult of the world. I have been grateful to still myself in the presence of the great Agnes Martin arrays at DIA Beacon, or to bring my concentration to the significance of clear shapes in Donald Judd. But this was a different movement. From absence to presence. The first time I had been able to see minimalism as a scaling up of impression. As an assertion of more.

**

The show is called Constant Structure, which is also the name of this work, which gave me, as soon as I beheld it, the confidence that seeing a work that will endure gives.

On the patio, before I had looked at the exhibition, Jenna Lyle of the Arts Club had mentioned that Jones had been thinking about Herbie Hancock. I wouldn’t say that I know Hancock’s work well, but it was helpful to have the recollection, a feeling of branches and spaces, just before looking.

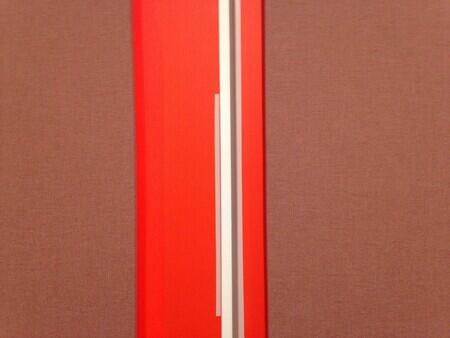

Detail, Constant Structure

This morning, to write this, I looked into it further. There is an interview with Jennie C. Jones by Jared Quinton published a couple of weeks ago in Bomb Magazine, and so I can quote the artist:

Constant structure is a chord progression consisting of three or more chords of the same type or quality. Brought to the fore by Herbie Hancock, it’s more or less a combination of functional and nonfunctional chords that create a cohesiveness while producing a free and shifting tonal center. This concept was something I gravitated to on multiple levels; it’s a poetic phrase in itself that seemed to encompass where I was in the “progression” of my work in terms of its vernacular, geometric vocabulary; or to continue the metaphor, the visual “chords” I’ve been building over time.

The works in the show are all from 2019 and 2020.

They are mostly acrylic on canvas or on acoustic panels. Acoustic panels absorb sound.

Detail, Constant Structure

In my experience of the show, the works were interestingly silent. Not mute. Not trying to speak. Deliberating and communicative. There is plenty to do in the realm of silence.

Detail, Constant Structure

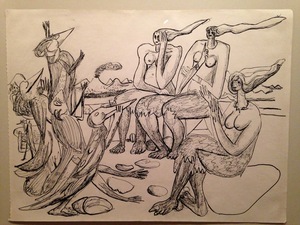

A few of the works are monotypes of ink printed on paper by Master Printer Marina Ancona at 10 Grand Press. These are hung behind glass, and my photos did not come out well. But in this one, hung a little separately in a stairwell, there was a reflection

The reflection is of a standing Calder mobile, commissioned for the Arts Club and part of its permanent collection, and the only work on view by another artist.

Alexander Calder, Red Petals, 1942. Plate steel, steel wire, sheet aluminum, soft-iron bolts, and aluminum paint.

In the neighborhood of Jones, the Calder became wonderful, its intervals clear and significant.

**

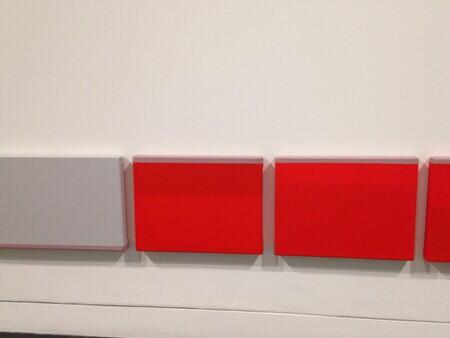

I loved many of them, but what I went back to was a pair hung together, Unit Structure #2 and Unit Structure #3.

Unit Structures #2-3, 2019-2020, Acoustic panel, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 x 3 inches.

Detail, Unit Structures #2-3.

The chromatic harmony is extraordinary.

Detail, Unit Structures #2-3.

The red and the brown are full of light together.

The equilibrium of the shapes and colors feels very free, so geometric, but not anxious like ‘I have to hold on to perfection,’ more like the steps of a proof in geometry, where moving through the stages is clear and perpetual.

Detail, Unit Structures #2-3.

I wondered whether the thin lines to the right of each central rectangle, one gray, one an orange of the red, were the same length and looked different lengths because of their surrounds, and this was a pleasant speculation.

The choice of color felt personal.

I think you do sometimes know, from palette, about the colors the artist has lived among, the colors the artist has been treated as, the colors the artist thinks of as important when they think about people.

I thought this was a celebration and one that let me be there.

While you are looking at it, coming up from the floor not too far from your feet is this wonderful work, which you have to get down to see.

**

In the front room, closer to the desk at which they take your temperature upon entering:

Deep Structure with Ledger Line, 2020. Acoustic diffuser; Acrylic on canvas. 2 parts 24 x 36; 12 x 24 inches.

Deep Structure with Ledger Line, 2020. Visible behind it is Corner Phrase / Dark Measure, 2020.

Oh, said Jenna Lyla, as she passed through – (I was in the midst of trying to memorize the planes of this piece, Deep Structure with Ledger Line, which I thought of as a raised speaker) – there is a catalogue, you are welcome to take one, the essay is by Fred Moten.

I would walk a mile to read an essay by Fred Moten, and now I had only to walk the twelve feet to where she stood, masked, and take it from her hand.

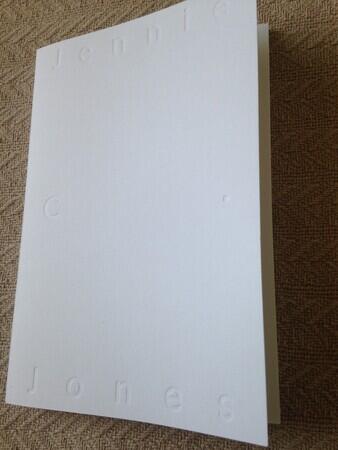

Constant Structure: Jennie C. Jones. With writing by Fred Moten. Designed by Ronnie Fueglister, the publication was printed at DZA Druckerei zu Altenburg.

The catalog is a beautiful object, a collector’s item. Designed by Ronnie Fueglister, printed at DZA Druckerei zu Altenburg. The prints are mostly of details of the works, and some of the works whole, and they have been printed softly, with shadows, so that they seem to have depths on the page. The texts by Fred Moten are called The Red Sheaves. They are shaped as concrete poems in what he calls parallelograms, every line break considered, and three falling as angled poems down the page. These are interspersed in conversation with the works. Writing alongside art is a special experience, when I have gotten to do it, I have asked for texts interspersed, it is so beautiful to get to write with, in accompaniment. In this case, it is the record of a conversation of endless interest.

Jennie C. Jones reports:

In many ways this was a playful body of work for me. Some of the gravity or anchor came from the collaboration with Moten, conversations I’ll cherish for a long time. It freed me up to be a maker and take some heavy, theoretical “explaining” off my plate.

When I came home, I greeted my family, and went upstairs to read through the little book. I read too fast for real comprehension and chided myself for not understanding. But this morning, on returning, I find the whole is perfectly clear, so it was anxiety and hurry and probably also the need to go away and come back and the desire to keep my own impressions of the works and not yet have them given a language. I have thought about the works for a day and a night now, have gone through my pictures several times and showed them to our daughter. Their resonance has not subsided, but it has clarified and taken hold.

In The Red Sheaves, one Moten parallelogram begins:

Try to imagine how to get a depth-feeling with words on the page.

In the middle of the next parallelogram my eye lit on:

"constant struc-

ture" is another way of phrasing what Amiri Baraka keeps aberrantly calling "the chang-

ing same."

Another text (the lineation is right, but imagine the right margin also justified):

We want what Jacques Derrida calls “structure without

a center,” a progression in which chords of the same quality

but with different root notes are played consecutively,

giving what they say is a free and shifting tonal center,

which seems to mean that if the center shifts, then it is not.

Then, it is a fugitive center, an eccentricity, which brings

to mind a changing, shifting structure, a moving structure,

a structure that can be felt—non-sensuously – in bring

seen, or even heard, to be more + less than cool reason

ever comprehends.

These passages stood out to me on the first reading, and were mentioned by Jones in the interview, and continue to seem crucial on each rereading.

The second-to-last parallelogram begins:

This book is just the three-dimensional representation

of our infinitely richer and more unruly two-dimens-

ional conversation. The book is just a volume, like a

room. The surfaces aren't flat; they're not planes.

They're plain.

**

Instances of being present at someone else’s conversation.

A couple of weeks ago, I gave a reading at a virtual bookstore in Ann Arbor, my home town, from my new book, which is in part a memorial for my father. Many old friends of my parents came to the zoom reading, as did some strangers, one or two of my former students and friends from other parts of life. Most people had their videos on, and the conversation among the zoom rectangles became a kind of memorial, very intimate, and people spoke to me as they might in other circumstances have done privately, of how they miss my father, and ways I am like him, things they would not have said in the bookstore before an audience, but which, gathered in tiles on the screen, could be said. This was an important experience for me, I felt exposed and a little strange, and also relieved.

Yesterday, I went to sit shiva on zoom for the mother of a dear friend. My friend is an artist with whom I once made a book where I wrote alongside her drawings, and it was her mother, whom I had known only a little, who had died. And I listened to the conversation among people who had known the woman who had died much more closely than I had. They spoke to one another as they might ordinarily have murmured in the corner of a room, but I was allowed to be there; my presence was not a constraint on the conversation, which they needed to have, and which by my attention I might even, in a small way, contribute to.

Constant Structure and the conversation catalogue were developed in the time before the coronavirus separated us all into our homes and screens, but seeing the show is like that, like being present for a conversation where people feel no need to hold back because you are there. My seeing the show was of course inflected by myself, but the show was not addressed to me, it was only conscious of me in the third person, and this gave me a tremendous freedom to be many different kinds of third person.

The artist is making work that she knows will be understood; the artist and the writer are confident in one another. The artist says she that this lifts a burden of explanation.

Neither the artist nor the writer have seen the show, it was hung on facetime, but it is there.