Memory that lives in the landscape -- John Constable

Friday, August 7, 2020

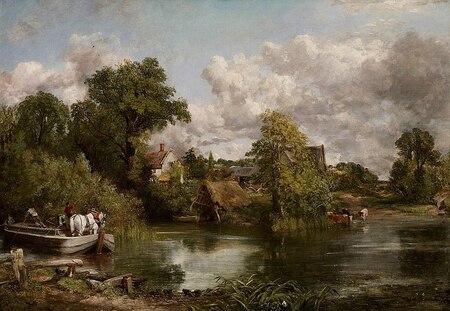

John Constable, The White Horse, 1819. The Frick Museum of Art.

A painting I have been thinking about this week is John Constable’s The White Horse, which is a painting I used to love at the Frick Museum and to visit regularly for many years. At that time, the Frick did not allow pictures, and I never took them anyway, and so I have no detail photographs of the kind I now use to go back and look, and can only reproduce here this distant internet picture.

John Constable, The White Horse, 1819, the Frick Museum, poor quality reproduction from the internet.

I have a kind of memory of paint that generally only comes back when I am in the presence of the picture, and can take up the same stance toward it that I have taken before. It comes from seeing the areas of paint in the picture with sufficient focus to see the layers that are not visible in a standard reproduction. I do not have the kind of memory that some great art critics have, where they can call up the quality of the picture, but if I am with the picture, then I can feel how I have looked at the paint before, the way a blue overlays a gray, and the resultant shimmer is something I know. It just feels nice to be in contact with it again. Sometimes this kind of knowledge adds together with other things to make an interpretation of the picture that is worth sharing, sometimes it is just a private pleasure.

Next week I am going to begin teaching Emma at the 92nd Street Y, and so I am thinking about the landscape of Highbury, the village almost populous enough to be a town, in which the novel takes place. It is in Surrey, a little to the south of London. The characters walk there, in detail, all through the book, and I have read it so much that I seem to feel the dirt and pebbles beneath the soles of my shoes, the thickness of the grass, the heat of certain days and drenching rain on others.

It turns out that you can see The White Horse very close up, through the wonders of the internet, at the Frick Museum’s website. When I went to look, I caught my breath. Reproductions had given me no sense of the time I had spent with the painting, but now I could see it. Especially the area of the water in the center, with its reflections, the way the water plants spike through the water. Especially something about the attitudes of the two figures on the boat with the horse, especially the small black birds wheeling in the clouds above the largest tree. It came back, the picture.

Here you can enter to see the White Horse at the Frick

A little more research uncovers that the oil sketch for this painting is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. They make their works available, so I can show this one, and something of the wonderful qualities of its paint. Here is it complete:

John Constable, The White Horse, oil sketch, 1818-1819, National Gallery of Art, higher quality reproduction from the museum's website.

Constable’s practice was to make these huge 4 x 6 foot sketches for each of his large landscape paintings. He painted the places he knew best, in his own country, in Suffolk, and particularly the valley around the river Stour. Now, with our modern eyes and preference for the free handling of Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism, many of us prefer the sketches to the finished paintings. And this is indeed a work of great beauty, which I saw in a wonderful exhibition of Constables at the Tate Gallery in 2006 which united many of the best known six-foot paintings with their correspondent six-foot oil sketches.

Here you can come closer to what the paint feels like:

The sketch has its own layered history, described in detail at “The Constable Project” on the NGA’s website. In brief, for a long time it seemed that the oil sketch Constable should have done for the White Horse, following his regular practice, was missing, but there was instead some kind of clumsy refinished copy of the Frick’s painting that didn't seem good enough to be a Constable. The museum's curators realized that someone had overpainted what was in fact the sketch, to try to make it look more finished and were able to strip away that layer to get down to the oil sketch, which lives now in all its resplendent and calm beauty.

Memory that lives in the layers – of dirt on familiar roads, of clouds in familiar skies, of paint in familiar pictures – that is what the regular traversal of a certain landscape may teach us.