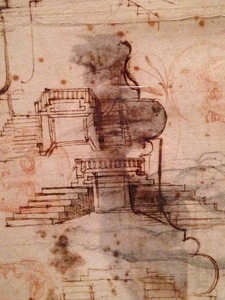

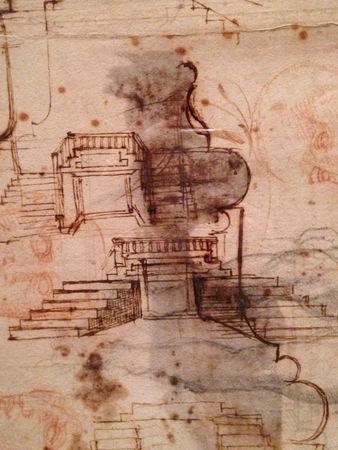

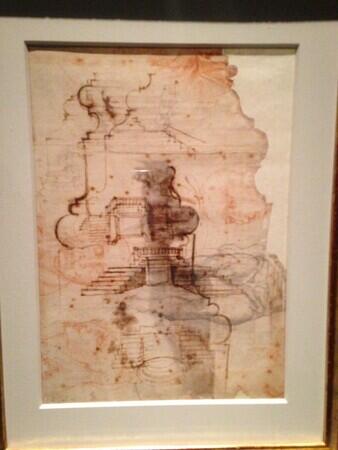

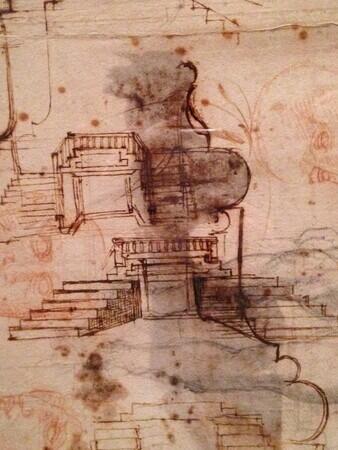

Michelangelo, Stairs for a Library

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Michelangelo, Designs for the Profiles of Moldings and Column Bases, Sketches of the Staircase in the Vestibule of the Laurentian Library; Figure Studies by a Pupil. Pen and brown ink, over red and black chalk. Casa Buonarroti, Florence. Photos Rachel Cohen.

While I was working on the biography I wrote of Bernard Berenson, which was published in 2013, I was able to go to Florence twice. This was before I had a phone with a camera, and I did not take pictures on these trips.

Berenson’s lists of Italian paintings and painters are still foundational for all the work of identifying who painted what in the complicated annals of late Medieval and Renaissance art in Italy. He was extremely gifted at discerning the artistic personality that had been at work in a certain piece – this is the way so-and-so does window casements in the background of a landscape, or this is a characteristic tilt of neck in a Madonna. And he was also very good at grasping the artistic personality of a city or region, which is a bit more diffuse, but, in Italy, coherent. City-regions were the organizing principle of Berenson’s series of introductory volumes about Italian art, volumes which educated many Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

**

Trying to understand Berenson’s way of seeing was interesting. I had traveled in Italy before, and had impressions of various paintings and places, but I made a concerted effort on those two trips to Florence. I fell in love with the sensibility, and it was like going over a cliff, it was so uncompromising.

It was a mathematical sensibility. One way to think of its origins is to imagine Donatello, Alberti and Brunelleschi all having little coffees together in about 1440 and talking over vanishing point perspective and bodies standing according to principle and the great domes and patterned ceilings of the churches that Brunelleschi had been building all over the city. It was not really utopian, it was clear. They had the math from the Arab countries of North Africa. Fibonacci had brought Hindu-Arabic numerals from Bejaia in what is now Algeria back to Pisa, and published a book about them in 1202 (these numbers had earlier traveled out of Sanskrit manuscripts). And the Florentines had the classical architecture of the Romans and the Greeks to study. And they were still devout, and thought in terms of realms. Sculpture, architecture, drawing, mathematics, these were ways to pursue an understanding.

Michelangelo came a century later – he grew up among the churches these three had built and decorated together – the chapel that Brunelleschi designed and Donatello did the sculptures for – the view of painting and sculpture that Alberti had codified in his books and that had shaped the great workshops of Florentine painting.

**

On one of the two trips I made to Florence, I went to the Laurentian Library. Built for the Medici collections, which were formidable, the commission was given to Michelangelo in 1523, and construction began in 1525.

They first completed the walls of the reading room, the long walls, background white, with pattern of inset gray columns and gray window shapes each with a cornice, the pattern of a building, as if in an architectural drawing of a façade.

The reading room walls set the tone for the project before Michelangelo left Florence in 1534. He continued to send plans and give verbal instructions to three other architects (Tribolo, Vasari and Ammannati) over the next thirty years. When Michelangelo died in 1564 the library was much closer to completion, though still not entirely finished when it was opened in 1571.

**

There are two spaces – the vestibule and the long reading room – and the colors of all the walls are gray and white. When I close my eyes and try to get back the experience of walking in, what I remember is mounting the stairs, a very peculiar feeling of flattened stone beneath my shoes and a kind of tilting, and then I remember the tranquility and clarity of the long horizontal reading room, and the desire to walk slowly all the length of it.

The vestibule is a vertical rectangular space, nearly half of which is occupied by a staircase of deep gray stone. This staircase was of the utmost importance. It had to convert height to length, it had to bring the humanist into the library, and his studies, it had to achieve movement and transformation within the rigorous scheme of architectural drawing that was the determined atmosphere of the space.

**

Michelangelo wrote a letter in 1555 that he had dreamed the design for the staircase. I can’t tell from the exhibition materials, but I think this dreamed staircase may be the one he worked on in these two drawings, on either side of the same sheet of paper.

In the dream version, it was to be two staircases that joined at the doorway. This was not what they built, which is one of the wonders of the architectural world, here reproduced in an internet photo:

This actual staircase was worked out later, in 1559, by Ammannati from a clay model that Michelangelo made for him. The clay model is lost. The resulting staircase is unified, with central, extending ovular steps, and two accompanying squared sets of stairs.

**

Even though it is an entirely different staircase, when I came upon the drawings in the exhibition in New York, some six or seven years after I had been in the library itself, I immediately knew the library. The drawings are done on what’s called a modano, a piece of paper cut so that stoneworkers could use it to cut stone for capitals and ornaments. The paper also has drawings of heads made by some of Michelangelo’s students, which he drew over and among.

Part of the exaltation, I think, comes from the fact that they knew it was a kind of strain on the human body, and on our perceptions, to enter this particular abstract conception. And that, when you went through this strain, you would be able to come into a different kind of contact with certain learning, developed by certain men and women, in Athens, Bejaia, Pisa, Florence.