Stockholder Rose's Inclination

Friday, May 22, 2020

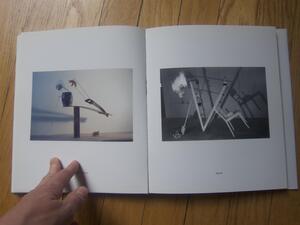

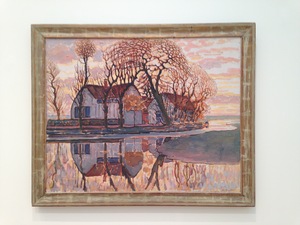

Jessica Stockholder, Rose's Inclination, 2015–2016, Paint, carpet, fragment of Judy Ledgerwood's painting, branches, rope, Plexiglas, light fixtures, hardware, extension cord, mulch, Smart Museum foyer, courtyard, sidewalks, and beyond. Commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago. Courtesy of the artist, Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery, and Kavi Gupta Gallery. Detail photos Rachel Cohen.

Red was also painted on to the sidewalk. The red stretched up in a big painted arc on the back wall that curved up on to the ceiling and stretched toward the windows of the second floor, windows that you cannot really see from the lobby space below but which shone on the red. And red ran in the carpet under the tables where students sat and drank coffee, across the floor of the lobby, out the museum doors, and on to the sidewalk, where it was met by triangles of yellow, blue, green, and lavender. The work felt red.

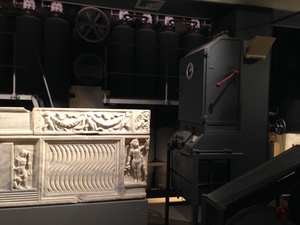

Inside, up on the wall that faced the great red curve there were lights, a great many of them, electric lamp lights of different kinds, and stretching across that space there were ropes, thick nylon ones of green and black, and there was a sort of large woven talisman, suspended among the ropes, and made of tree branches and of orange and other colored yarn. The whole thing was a very unusual combination of loftiness and invocation and wryness, and it made me laugh.

Rose’s Inclination by Jessica Stockholder, was installed at the Smart Museum of Art for two years, from 2015-2017, and was there when we arrived in Chicago, so that it became the museum for me. Three years have passed since it came down, but I still sometimes miss it when I walk into the lobby. And the way I miss it is a little like the way I miss the large, gangly, beautifully soft viburnum that had to come out of our garden because of the beetles, and which had a personality that was a part of the whole. But Rose’s Inclination was much larger and more intelligent – she had a force and dynamism.

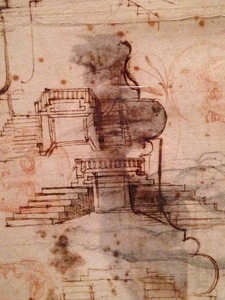

When I stood looking up at Rose’s Inclination, I sometimes thought of Marcel Duchamp’s alter ego, Rrose Sélavy (Rose, c’est la vie) and of his Large Glass with the intricate relationships among the absurd parts that nevertheless give a sense of bodies and personalities.

The whole system of Rose was there in Rose’s Inclination, the lamps and ropes and paint and branches she needed for the currents of her energy and ambition to flow. And Rose even seemed to have outgrown her artist, which suggested a fearlessness on the part of the artist that was very delightful – to see an artist with such powers at work and at play at once.

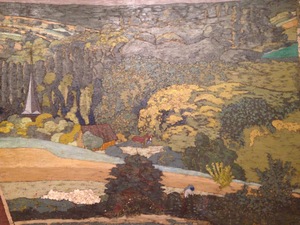

I’m not sure I can think of another work I’ve seen that actually seemed to grow, not just to move, but actually to share with plants the activity of growing before one’s eyes. In this week, where I am thinking about vegetation, about Vuillard, Mondrian, Vostell, about plants and the kinds of abstract understanding they make available, about material — tapestry, paint, water, concrete, leaves and stems — and the way it may derive itself and send itself forth — this week, I have been leaning forward to get back to Rose's Inclination.

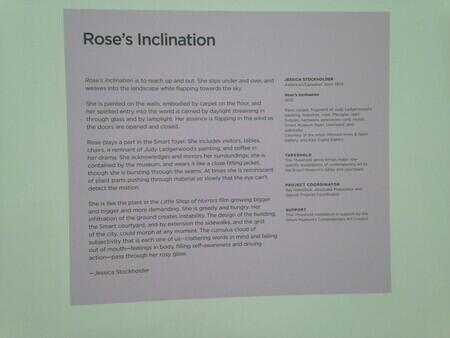

Jessica Stockholder is a colleague at the University of Chicago, and a wonderful writer. The wall text she wrote for Rose’s Inclination was not especially large, and was an indispensable part of the experience. This is how the wall text looked.

Here is the artist's writing in full:

Rose’s Inclination is to reach up and out. She slips under and over, and weaves into the landscape while flapping towards the sky.

She is painted on the walls, embodied by carpet on the floor, and her spirited entry into the world is carried by daylight streaming in through glass and by lamplight. Her essence is flapping in the wind as the doors are opened and closed.

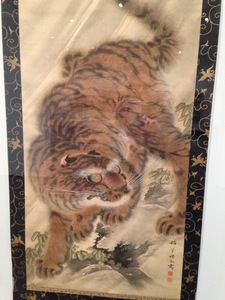

Rose plays a part in the Smart foyer. She includes visitors, tables, chairs, a remnant of Judy Ledgerwood's painting, and coffee in her drama. She acknowledges and mirrors her surroundings; she is contained by the museum, and wears it like a close fitting jacket, though she is bursting through the seams. At times she is reminiscent of plant parts pushing through material so slowly that the eye can’t detect the motion.

She is like the plant in the Little Shop of Horrors film growing bigger and bigger and more demanding. She is greedy and hungry. Her infiltration of the ground creates instability. The design of the building, the Smart courtyard, and by extension the sidewalks, and the grid of the city, could morph at any moment. The cumulous cloud of subjectivity that is each one of us—clattering words in mind and falling out of mouth—feelings in body, filling self-awareness and driving action—pass through her rosy glow.

— Jessica Stockholder