library of exile

Tuesday, December 29, 2020

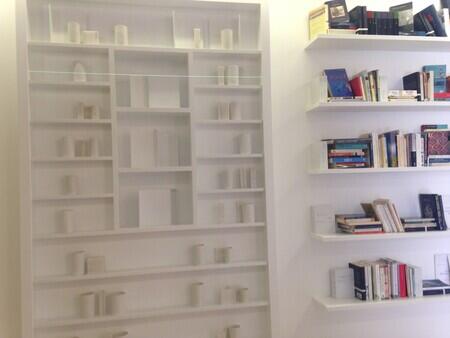

Edmund de Waal, library of exile, installation Ateneo Veneto, Venice, 2019. Photo Rachel Cohen.

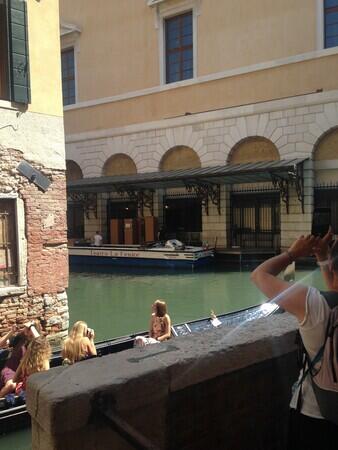

I saw Edmund de Waal’s library of exile installation in the summer of 2019, in Venice. I went in the morning. My mother had the children, and while I was gone T dropped his gondola souvenir on the stone floor and the little glittering aqueous globe with the tiny buildings of Venice in it smashed on the stone floor and water went everywhere. They went to the little souvenir shop and bought another one for a few dollars.

But I did not know of this. I took the vaporetto, a grown up, a lover of art, with a map, purposeful, and I walked this way and that way in the turning streets.

La Fenice, Venice, June 13, 2019. Photo Rachel Cohen.

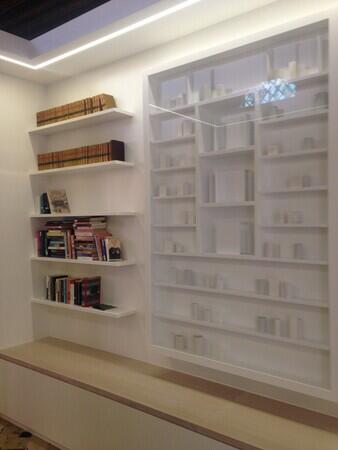

And I came to the little campo near La Fenice, and the entrance to the Ateneo Veneto. Inside, there was a beautiful square old room, of a kind that Henry James and Isabella Stewart Gardner loved in Venice, with dim paintings on the ceiling and worn burnished ornaments, and inside that room there was a white room, white walls not that tall, with no ceiling, like a cabinet, like a theater. On these white walls there was handwriting, scribbled notes and quotations. A small room inside a room that reminded me – because of the handwriting in the white paint, because of the understanding that white could be a thoughtful, accumulative, difficult color, not of dominance or whitewashing – of the Cy Twombly sculpture room at the Art Institute of Chicago. That room has Twombley’s white-painted conglomerate sculptures and the installation as a running frieze above it of Felix Gonzales-Torres’s “internal self-portraits,” the work “Untitled, 1989,” painted words and dates, that make another consideration of a departing life around the top edge of the white walls.

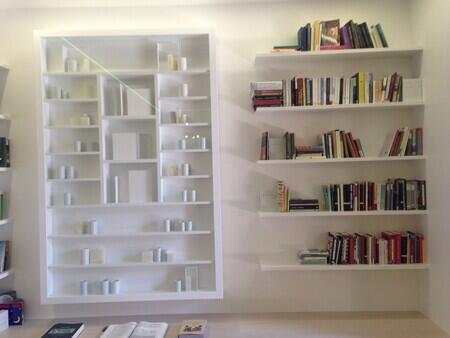

This is an installation photograph cribbed from an article in Wallpaper and photo not credited. I think it may be by photographers Hélène Binet & Fulvio Orsenigo.

Inside the de Waal walls was the library of exile. Books about exile to be collected and donated to the University of Iraq in Mosul, where the library has to be rebuilt. library of exile is imagined like an ivory seed, to be given to the rebuilt library of Mosul, where it may take root and grow.

library of exile installation photograph, possibly by photographers Hélène Binet & Fulvio Orsenigo.

I did not realize at the time that the walls were made of poured porcelain, but this explains their special quality of lustrousness and depth. Names of destroyed libraries inscribed, and quotations about libraries gone, some from the artist’s family.

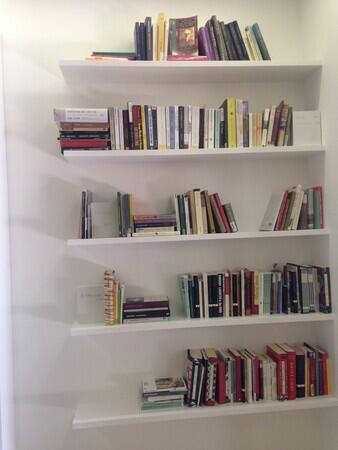

Edmund de Waal, library of exile, installation Ateneo Veneto, Venice, summer 2019, photo Rachel Cohen.

The books inside are the books on my shelves, too – Ovid, Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Cavafy – and many others. Ovid mattered to Mandelstam – each exiled writer carries in mind the library of books by other exiles. You can take the books down off the shelves, read for a few minutes. You can sign your name on the bookplates of books that have mattered to you. I don’t remember now; I signed a volume of Mandelstam, I think. You can suggest books, too, that should be part of the library. I suggested several books, which, as far as I can tell, have not been added to the library, but you can page through many necessary books by many writers that are in the library at the project website, linked below. I suggested the works of Aleksandr Hemon, Lawrence Weschler's Calamities of Exile, and Lina Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas’s Don’t Come Back, published by Mad Creek Books, which is about leaving Colombia, and draws out the kinds of exile that happen when you come to not returning, even though what has sent you away was no formal injunction, no commanding paper with your name on it, just violent structures that will, with mechanical probability, destroy you if you stay.

The exilic is a condition we know. We depart. We calculate in years how long we have before we will have to leave – the shoreline, the rainforest, the farmers’ fields, the clogged cities, the flooded plains, the fenced camps, the places the newspapers will soon call ‘long-simmering’ though they seemed peaceful enough not long ago. We increasingly speak of other planets as future homes.

Edmund de Waal, library of exile, installation Ateneo Veneto, Venice, summer 2019, photo Rachel Cohen.

Next to the shelves of books were shelves of pots, made by de Waal. Austere, human. I took them to express de Waal’s sense that making pots and writing books are very similar kinds of work. Two technologies of genius – the ceramic, the printed – for enclosing rootless spirit. I learned later that he organized the vitrines of pots to echo pages from a venerable edition of the Talmud printed in Venice in 1520-1523.

I follow de Waal’s Instagram and each of his posts – of pots he has made, of lines from a poem that he hears in his head – can reside in the room of the library of exile he made and which I now carry in my mind. Like all organized collections, it is very near to the ghostly. The books are worn, but not in celebration, they are worn as a stone planed by time. The candle is snuffed, the time is late.

The library of exile is at the British Museum until the 12th of January, but the museum is closed because of the pandemic.