Liz Magor at Passover

Sunday, March 28, 2021

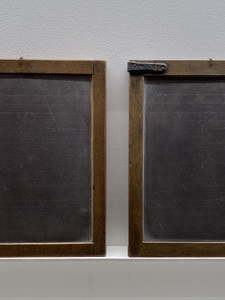

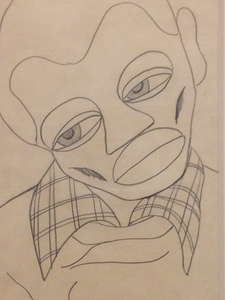

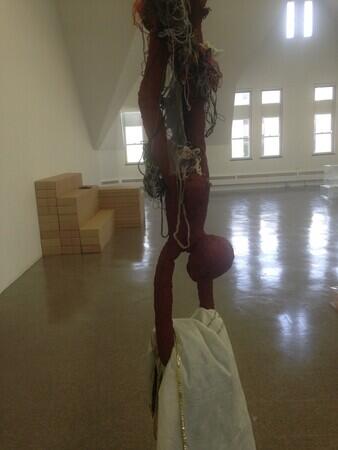

Liz Magor, Blowout, installation at the Renaissance Society, Chicago, Spring 2019, all photos Rachel Cohen.

I have been twisting myself toward spring cleaning. My right hip and lower back aren’t what they were. It is hard to get a clear mind, and the house is encrusted with the layers of our going through this year. On my desk, the notebooks with promising scraps of ideas are buried beneath an avalanche of the undone tasks of several years. Books are everywhere, as are the children’s projects, stiffened clay, half-sewn dinosaurs, still unstuffed. A metal model tower that didn’t work out awaits an uncertain fate in one of the myriad little white dishes we use for every purpose that I bought for a dollar each six years ago to be the dishes for salt water, for dipping the parsley, when we were in Cambridge, and we had a big Passover, guests at two tables, friends since scattered on two continents.

For a week now, I keep thinking of a spring show at the Renaissance Society, here in Chicago, the works of Liz Magor. It was called Blowout. Co-curated by Solveig Ovstebo and Dan Byers in 2019. Solveig has since returned to Oslo, to the Astrup Fearnley Museet, another person I would have liked to stay in the same city with. I had my class see the show. Another Ren curator, Karsten Lund, arranged for us all to come to the conversation with Sheila Heti, who had written the catalogue text.

My associations will be obvious from the pictures. This odd plastic in which the objects – which have not only the wornness but the stickiness, almost disgustingness of domestic life, matted fur of syrup and dinosaurs, soiled clothes, what-is-this-thing-must-we-keep-it-how-does-one-even-dispose-of-it and also the corporateness of domestic life, the rows of shoes, hardly worn or not at all, the objects that promise a slightly spiffier more convenient life, rain hats that never did fit, sleek kitchen gadgets still untouched at the back of drawers, the blandishments of advertisers to which I succumbed – all of this wrapped, cherishingly, solemnly, to me also despairingly, in envelopes of gelid plastic. What might be less obvious is the peace that was to be felt in the space, an uneasy peace, that was differently reassuring. Not the peace of respite, which always contains the melancholy of its evanescence. Nor the peace of acceptance, so life is, which holds the guilt of acquiescence. Just uneasiness in a form you could look at, with good light. Lucid uneasiness.

At Passover, in late March, early April, one cleans the house, airs the house, beats the dust out of rugs, scrapes the dead mulchy leaves off the new shoots of plants in the garden, sweeps up all the crumbs of bread. We are to think of liberation, to sympathize with those who have to flee from their places and things, no time for yeast. Sanctimony beckons. And so does survivors' guilt, and the defensive accumulation upon which capitalism plays like a harp. The story, though, I am trying to hear it, I think it knows we are not yet free. If I can find our actual multitudinous selves, who hunger. We are to tell the story of the exodus as if we ourselves were there; to the story it may be all one problem. One gives a few of the miniscule clothes and unbroken wooden toys to other families, while keeping most of them, sentimentally, inexplicably, in the sordid basement, puts the books back on the shelves, removing what sticky dust one can from them, so that they can await another year, when their meanings may at last be drawn together… a deliberately unending ritual, not yet, not yet.