Three Pissarros Over Time

Monday, May 4, 2020

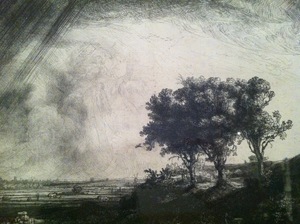

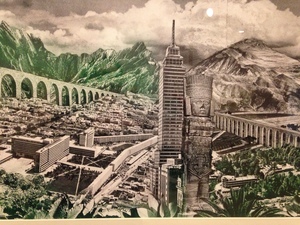

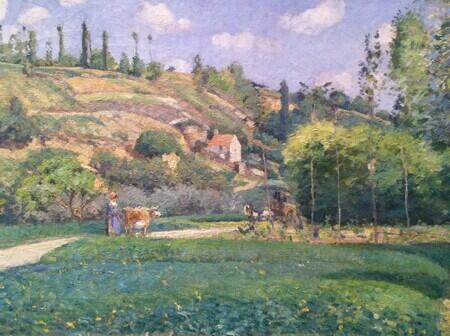

Camille Pissarro, A Cowherd at Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1874. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photos Rachel Cohen.

A Pissarro landscape has a special quality. As in a Monet, the vegetation has a lift, but this is even a bit more pronounced, so that there is a strong space around the leaves, which have a kind of brio.

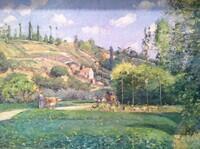

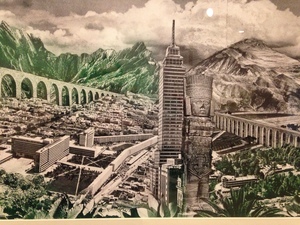

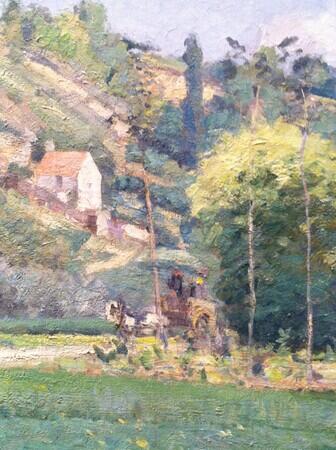

Detail from Camille Pissarro, A Cowherd at Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1874.

As in a Sisley, there are glints, and the overall effect is quite bright, but the strokes are not quite as thin as Sisley’s.

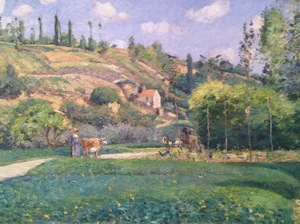

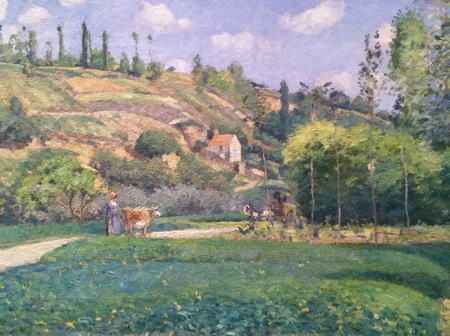

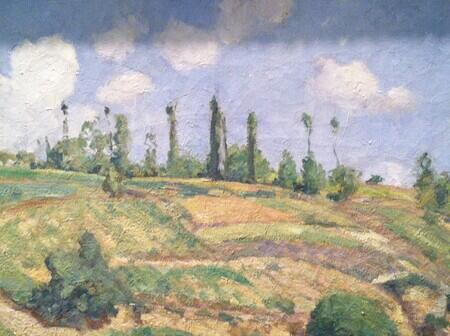

Camille Pissarro, Cotes des Grouettes, near Pontoise, probably 1878. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photos Rachel Cohen.

*

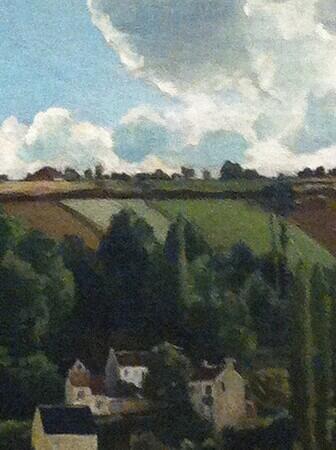

To understand the painter who emerged in the 1870s, it is useful to look back a little into his history. Like all of the central generation of Impressionists, Pissarro followed Manet through the 1860s. Paint is smooth and areas of color fairly large, as here, in 1867, Jallais Hill. Beautiful, and with a certain opacity, something the eye moves over, but there is an incipient sense of through.

Camille Pissarro, Jallais Hill, 1867. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photos Rachel Cohen.

Detail from Camille Pissarro, Jallais Hill, 1867.

Pissarro and his companion, later his wife, Julie Vellay had to flee Paris during the Franco-Prussian War. When they returned in 1872, they found that the Prussians had destroyed more than 1400 of his paintings done over twenty years. So the record of his early understanding of landscape, and of paint, is incomplete. Some think that these destroyed paintings would have shown the birth of Impressionism. This one from the Met is one of only 40 that remained, and becomes important in showing the great spatial and geometric clarity that underlay all his work.

Detail from Camille Pissarro, Jallais Hill, 1867.

Detail from Camille Pissarro, Jallais Hill, 1867.

By 1874, look how the mass is made with freedom and movement. How many colors are stippled through one another. This is how form and space are made.

Detail from Camille Pissarro, A Cowherd at Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1874.

Detail from Camille Pissarro, A Cowherd at Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1874.

Detail from Camille Pissarro, A Cowherd at Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1874.

1874 is the year of the First Impressionist Exhibition, brought about in large part by Pissarro and his activity, his work as a uniting force. He was a primary articulator of the injustice of the old Salon system; he was always strong in his defense of working people as subjects of art; having grown up a child of Jewish shopkeepers in St. Thomas, he understood the dynamics of the colonial world and its cosmopolitan capitals, and this allowed him to see landscape, its cultivation and its colors, with a different kind of eye.

*

Pissarro, ever alert to new developments, joined Seurat and Signac in the pointillist movements of the 1880s, taking color juxtaposition to an extreme. Perhaps these theories felt like a confirmation of convictions he’d had all his life about how to make space by the application of small areas of color; he would say that he preferred the scientific to the romantic. The three landscapes I am looking at here are not from this pointillist period, but they are not disconnected from Pissarro's steady experimentalism.

Going back through my own entries on Pissarro, I find that it was seeing these landscapes in 2013 that first allowed me to start my own method of photographing the details of paintings. Pissarro himself was not as interested in photography as Degas and Caillebotte and others who were serious photographers. But he was very modern.

Landscapes by Pissarro might seem a little less than Monet, not as powerful in their color, not as complete and radical an accomplishment as Monet's great series paintings or his late abstract works. What makes them so strikingly modern is a little hard to identify.

What I see thinking about these three paintings today is a definiteness and clarity, a structure in space that emerges over time, and comes not in spite of gentleness or nuance, but somehow together with these qualities.

Pissarro wrote a volume of letters to his son Lucien, a volume now famous, but at the time a strong record of the running thoughts of a gifted and impoverished man. [My edition is the one edited by John Rewald in 1943, and later translated by Lionel Abel.]

On November 20, 1883: Remember that I have the temperament of a peasant, I am melancholy, harsh and savage in my works, it is only in the long run that I can expect to please, and then only those who have a grain of indulgence; but the eye of the passerby is too hasty and sees only the surface. Whoever is in a hurry will not stop for me.