Valeria Luiselli and Lola Álvarez Bravo, Changes in Scale, Part 1

Thursday, April 30, 2020

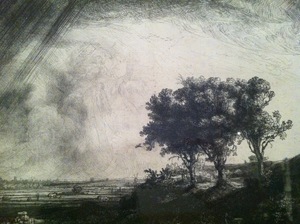

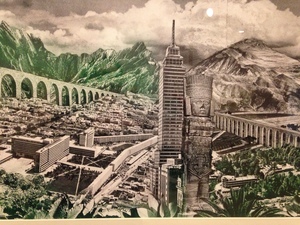

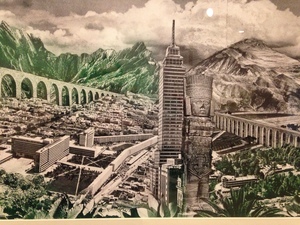

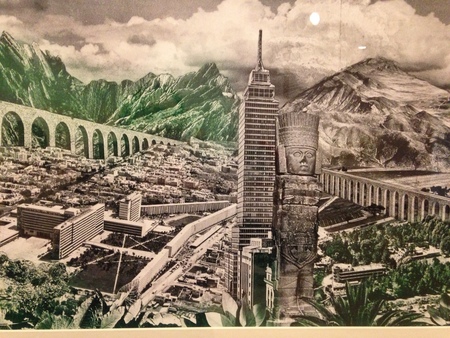

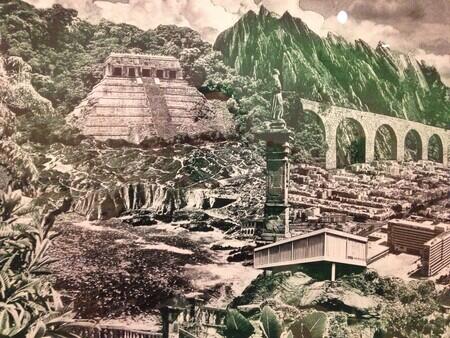

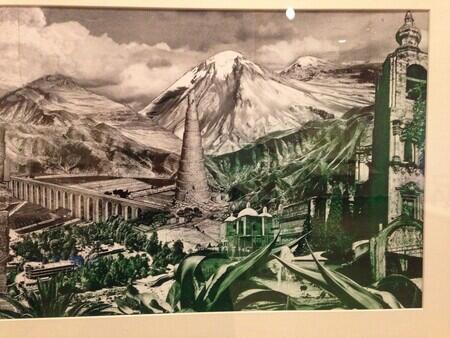

Lola Álvarez Bravo, Landscapes of Mexico, ca. 1954, photo-montage. Familia González Rendón/©Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona/Rodrigo Chapa. Detail photo Rachel Cohen.

Low this morning, daunted by similar days and already anticipating the evening feeling that the day has slipped by without any of the things I meant to do getting done. I am aware that today was to have been a special day. We had been able to invite Valeria Luiselli to come to the University of Chicago, and she was to have arrived yesterday. Tonight would have been the large public event. I would have met her yesterday, be going over my introductory remarks now.

These last few years, Luiselli has been a writer who has mattered very much to me. I read Tell Me How It Ends not that long after we arrived in Chicago. Picked it up at 57th Street Books because they had it prominently displayed. And then read it on my feet, walking around the neighborhood, unable to put it down, or to stand still as I took it in.

After the 2016 election, I had started a project called Migration Stories, and, when I found Luiselli’s book, was planning to teach a class called Writing in Crisis, about writing in the midst of crises, when you don’t know the end, and so you can’t determine the shape of your piece by how the story will come out. And here was a book about the crisis of unaccompanied children that took on this formal problem in its title and on every page. These children, sent or sent for by their adults, arriving to bureaucratized cruelty. Part of the cruelty, and part of the difficulty of doing ethical justice to their situation, was that no one knew how their stories would end.

I teach this book every year. The brazenness of our government's cruelty gets worse. And Luiselli has given new dimensions to her reflections by writing a related novel Lost Children Archive. I also teach another book of hers, an earlier set of essays, very visual, and grounded in Mexico City, translated by Christina MacSweeney and called Sidewalks in English, but published as Papeles Falsos (False Papers) in Spanish. I wish I could talk about Tell Me How it Ends and Sidewalks with their author today.

*

Today I am thinking about changes in scale. Part of what marks modernity as modernity is abrupt changes in scale. A few people are eating a kind of food, listening to a certain singer, traveling from one city to another, suddenly many hundreds of thousands can buy this food, packaged, can listen on the radio, can board a train. Part of what we are doing in lockdown is an experiment in scale unlike any I know of in human history.

Landscape changes scale like this – mountains rise up suddenly, there are cliffs and canyons, and the human landscape does, too – in its monuments and skyscrapers and airports. The bigger the city, the more it forces us to think about changes in scale – how crowded are the places for people who are poor, how high up are the places for people who are rich, what is industry next to, who is close together in a factory. Human problems are also formal problems.

*

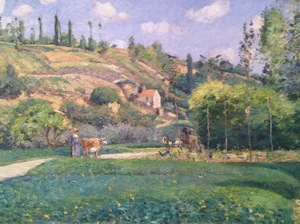

In the fall of 2019, there was a show at the Art Institute of Chicago, curated by Zoe Ryan, called In a Cloud, In a Wall, In a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico. It considered the work of six artists who began in different places and spent significant time in Mexico City: Anni Albers (Germany, fled in the 1930s, United States), designer and curator Clara Porset (who left Cuba, arriving in Mexico City in 1935, and living her life in Mexico thereafter), sculptor Ruth Asawa (born in the US, of Japanese origin, who was a child in an internment camp in the US during WWII), textile artists Sheila Hicks and Cynthia Sargent, and photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo, who moved to Mexico City with her father at the age of three.

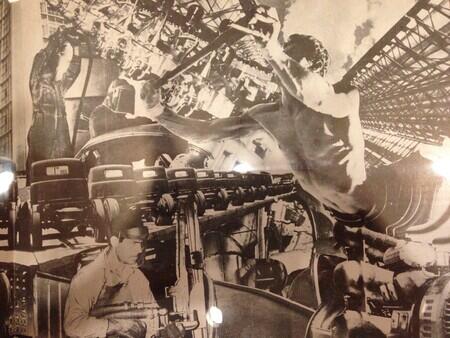

I first saw the show with my friend and colleague Ben Lytal, a novelist. We were immediately struck by the photo-montages of Álvarez Bravo. Here is a hasty shot of the huge blown-up one that opened the show:

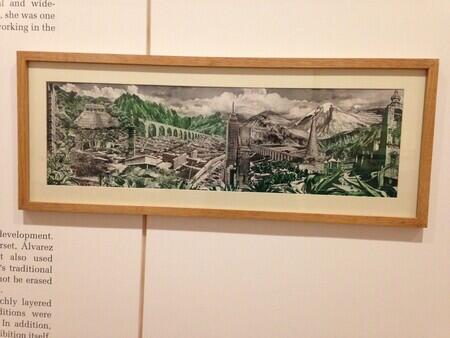

We stopped before another one, a long horizontal piece, called Landscapes of Mexico. Ben said that it made him want to write, if I remember, he felt he could spend hours studying this work and practicing the things it made him ambitious to do. My photo of the whole of it is hard to make out, but gives one sense of scale:

*

In Papeles Falsos, Valeria Luiselli has a wonderful essay called, in translation, “Flying Home” that I taught last fall, on difficult-to-decipher landscapes of Mexico City, particularly all its waterways that have been drained or filled in and covered over. Its many missing lakes, the names of which make the titles for the essay’s sections, making a landscape of their own, a collage in letters. Luiselli’s essay takes many perspectives on the landscape – seen through the dusty corridors of a geographical archive, seen in maps of different historical eras, seen from the air.

This morning, I reread the essay; as I half-remembered, it is interesting to think about the essay and Bravo’s photo-montage together. Tomorrow, I will try to work through that here.

The essay begins aerially. Or with the irritating cartoon-maps shown on airplanes in which one makes infinitesimal progress toward a landing place. Here is the essay's third paragraph:

No invention has been more contrary to the spirit of cartography than these airplane maps. A map is a spatial abstraction; the imposition of a temporal dimension—whether in the form of a chronometer or a miniature plane that advances in a straight line across space—is in contradiction to its very purpose. As surfaces that by nature are immobile and frozen in time, maps don’t impose any limitations on the imagination of the person studying them. Only on a static, timeless surface can the mind roam freely.