Valeria Luiselli and Lola Álvarez Bravo, Montage, Part 2

Friday, May 1, 2020

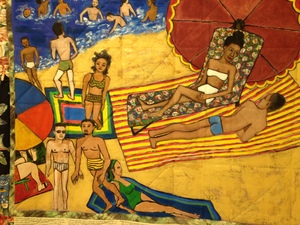

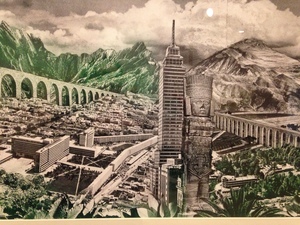

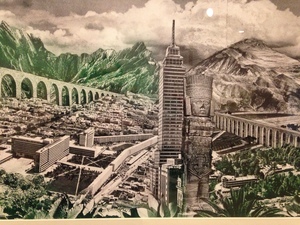

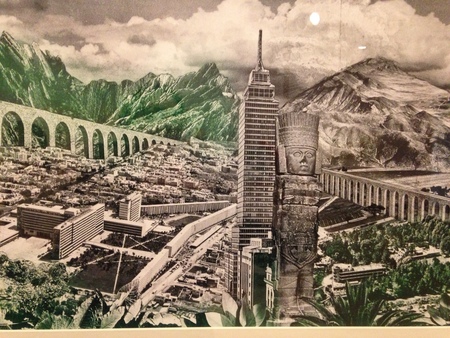

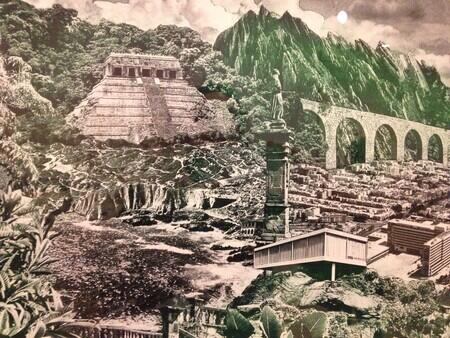

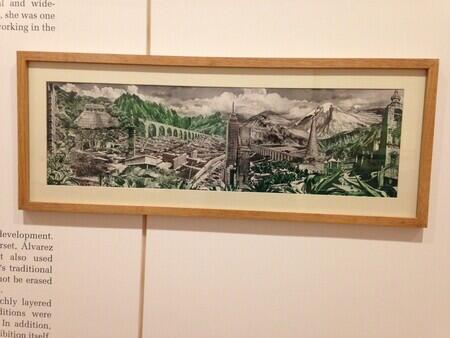

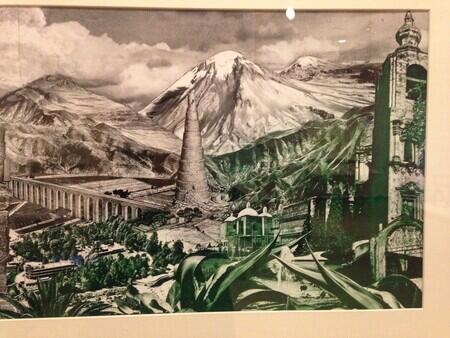

Lola Álvarez Bravo, Landscapes of Mexico, ca. 1954, photo-montage. Familia González Rendón/©Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona/Rodrigo Chapa. Detail photo Rachel Cohen.

Continuing the thought of yesterday. Two artists consider the topography of Mexico and Mexico City. Lola Álvarez Bravo in a photo-montage called Landscapes of Mexico from around 1954; Valeria Luiselli in an essay from around 2012 called “Flying Home.” [I’m using the translation by Christina MacSweeney; I don’t know what the essay was originally called in Spanish.]

Both artists consider shifts in point of view that are hard to come by right now – you can’t get up into an airplane, or into the dusty reaches of a map archive, or to the top of a skyscraper to take photographs. From the windows of our rooms, available perspectives are constrained, and there is a corresponding longing for the kinds of spatial variety these artists collage together.

Part of what interests me is the way the same formal process of splicing together may apply to space and to time. The Álvarez Bravo takes modern buildings, ancient monuments, mountains and valleys – things which arise and erode in completely different scales of time – and juxtaposes them.

Juxtaposition seems like a modern technocratic word, loved by academics, but it is an older, deeper word, coming into English in the 1660s, from a 17th century French coinage combining the Latin iuxta, joining, with the French position. By the 17th century, with colonial projects well underway around the globe, this sense of placing distant things next to each other by force or abstraction needed a word.

Luiselli: We need the abstract plane to move around easily, to ravel and unravel possible journeys, plan itineraries, sketch out routes. A map, like a toy, is an anology of a portion of the world made to the measure of the eye and the hand. It is a fixed superimposition on a world in perpetual motion, made to the scale of the imagination: 1 cm = 1 km.

Álvarez Bravo is a master of self-aware juxtaposition. She leaves spatial scales incommensurate – a Baroque church towers over a mountain, what must be a large modern building is tiny compared to a brick tower that would have been built before the Spanish arrived – and in this way, she holds on to the distinct sense of time that belongs to each.

*

Cities are high and low in time and in space, in history and in architecture.

The writer in “Flying Home” goes to the city’s map archive, housed in the National Meteorological Service Building. She searches through huge tomes to try to learn about the drawing of the border between Mexico and Guatemala. Then she tries to locate the city:

When I asked about the maps showing the original plans of Mexico City, the curator apologized and told me they didn’t exist. Legend has it that a Spanish soldier, a certain Alonso García Bravo, traced the design directly on to the ground. There are maps of the city from the sixteenth century, of course, but none precedes the grid plan of the historic centre. García Bravo made a few scratches in the damp earth somewhere around 1522 and became the first urban planner of the great capital of New Spain. It’s no surprise that it happened that way. Every inhabitant of Mexico City suspects it: if a sketch of the city has ever been made, the pencil scarcely touched the paper, and what is now called ‘urban planning’ is pure nostalgia for the future.

I see different ways to read that phrase “nostalgia for the future.” It could be the nostalgia of a reader now looking back at those first plans, and knowing the kind of planning that was to come in a future still embedded in our past; it could be the makers of the early plans, longing for, and imposing on, a future that they hoped would recall their past. Luiselli’s passage is also a collage. Points of view in time double up on each other, but keep their different senses of scale.