Delaney and Morisot Ochre: This Week in Self-Portraits

Friday, April 24, 2020

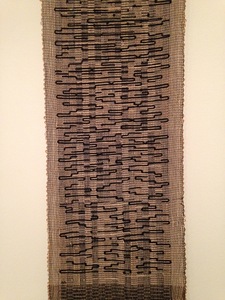

Beauford Delaney, Self-Portrait, 1962, detail. Collection of halley k Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld. Photos Rachel Cohen.

Yesterday, looking at pictures of Beauford Delaney’s Untitled, 1965, I noticed a kind of ochre in the corner that I hadn’t remembered being part of the palette. It's down in the lower right corner, near the rosy orange, under the diagonal of green.

I have also been going through Morisot paintings this week, and her self-portrait, with its ochre, came into view.

Berthe Morisot, Self-Portrait, 1885, Musée Marmottan Monet. Photos Rachel Cohen.

Ochre was so important that she used it to show her own palette, the physical artist's palette that she the painted painter held:

*

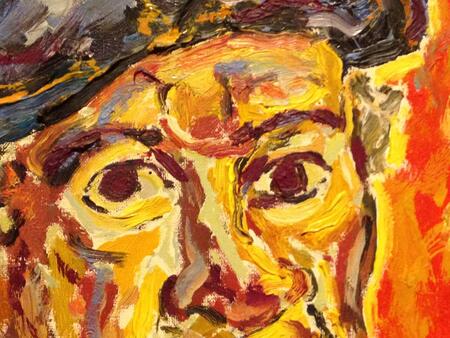

Following ochre, I started to think about the two of them together. Which I anyway do fairly often because two shows – Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist, and Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door – have been two of the deep experiences of learning about a painter that I’ve had in the last three years. Here is a self-portrait Delaney did that is, among other things, a consideration of ochre.

Beauford Delaney, Self-Portrait, 1962. Collection of halley k Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld. Photos Rachel Cohen.

Both are painters who have been difficult to see – with works widely dispersed and a very large number in private hands. Both long under-recognized, so not part of every large group show on Impressionism or Modernism. Both were courageous, independent, and, about painting, self-assured.

At what layer of presence does a person’s perception of themself reside? Is it the innermost layer, private and nearly inaccessible to anyone else? Or is it the outermost layer, where they present themself to the world? Or is it just beyond the edge of the self?

Part of what I love in both Morisot and Delaney is the way layers over- and under- layer.

*

Learning as I go, I look up ochre. It is a family of pigments — red-yellow-brown. It comes out of the earth, and all the members of the family have in common the presence of iron oxide. It is the ferric element that gives the yellow. Earliest artistic use uncovered so far: pieces of ochre with abstract designs carved into them at the Blombos Cave in South Africa, 75,000 years ago. Used on every continent inhabited by people, important in cave and mural work among Aboriginal people, Greco-Romans, Egyptians.

Both Morisot and Delaney would have used ochres that came from the Vaucluse part of Provence in France, where the famous red and yellow cliffs were the central source for the finest pigments for artists for two hundred years, after Jean-Étienne Vastier discovered the method of refining that clay in the 1780s. So there is also a mineral proximity.

*

The Self-Portrait, 1885 is the main Morisot self-portrait. Delaney painted himself many, many times. Each also painted another person at all the stages of that other person’s life. Delaney painted a man he was friends with, and mentored, and loved, James Baldwin, whom Delaney first met when Baldwin was still a teenager. Morisot painted her daughter Julie (nearly a third of her paintings are of Julie).

Morisot painted the 1885 self-portrait in between the paintings of her daughter that I showed earlier this week. Her daughter was growing beautifully, was observant, was interested in painting and loved her mother's painting; they were close.

Delaney painted this self-portrait in 1962, in a year when he moved back into Paris after several very important years living in Clamart, outside of Paris, where he had really understood his own abstract style, and where he had often sat in the evenings with Baldwin looking out a window together.

Seeing yourself in other people, seeing other people and being free of yourself for a while, taking pride in someone else, all of these may let a self-portrait swing out.