iris Kensmil and Remy Jungerman at the Venice Biennale

Frederick Project: Before and After

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

iris Kensmil, The New Utopia Begins Here #1, 2019, acrylic paint on wall, oil on canvas, 550 x 1596 cm. Installation The Measurement of Presence, curated by Benno Tempel, co-artist Remy Jungerman. Installation photo Rachel Cohen

Last summer, in 2019, we went to Venice with my mother. My father had close colleagues at the University there, and my mother still goes regularly to see them and the city. I had not been back since we scattered my father’s ashes there, six years earlier.

Now our daughter was seven, our son four. They loved Venice. They loved that there was a boat for everything – for garbage, for fires, a UPS boat, one with a crane for construction, gondolas and pleasure boats and water taxis. The world was aqueous, as it is in certain places on the globe – in the Netherlands, in the Caribbean, along the coast of Suriname.

One morning my mother took the children, and I went to the Venice Biennale. I had never been to the Biennale before, and I was pleased to have a morning on my own. I took a crowded vaporetto bus down the Grand Canal, found the entrance, paid the large entrance fee. It was a bright, hot day.

I went to see the Martin Puryear installation, which was very fine, and then wandered about – some things seemed amateurish, some commercial, some so on-the-nose that, even when I agreed with the political message, the artistic experience didn’t come. I had agreed to all this, when I decided to spend the morning in pursuit of contemporary artistic experience, and I felt phlegmatic about it.

I walked into the Dutch pavilion, designed by architect Gerrit Rietveld, built in 1954. Open, very bright, clearness.

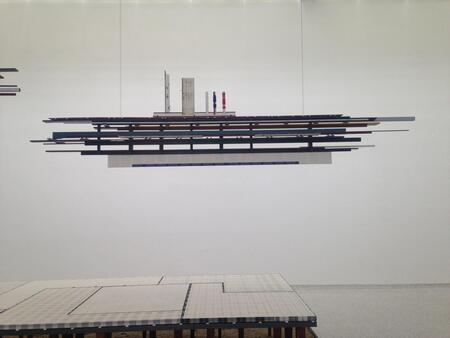

Immediately these three suspended structures, which to me seemed at once like boats and buildings:

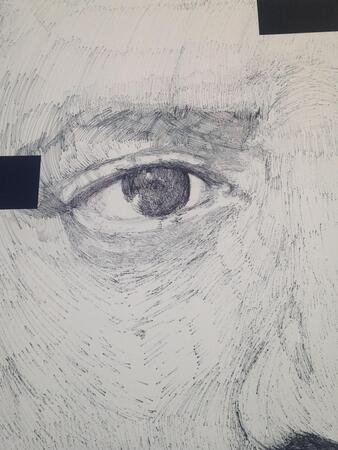

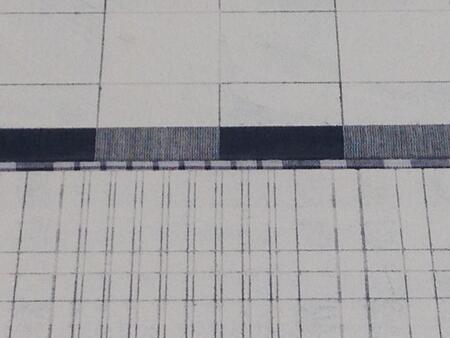

Sometimes the eye knows fineness of conception and workmanship so quickly. Judgement/guess that this was meaningful borne out in looking more closely:

The nails seemed full of meaning.

I turned to see the rest of the space.

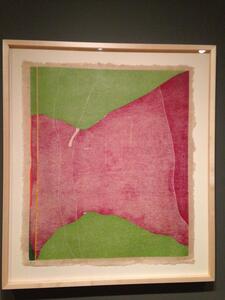

Another work by the same artist:

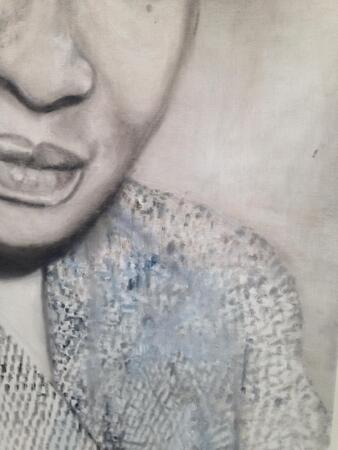

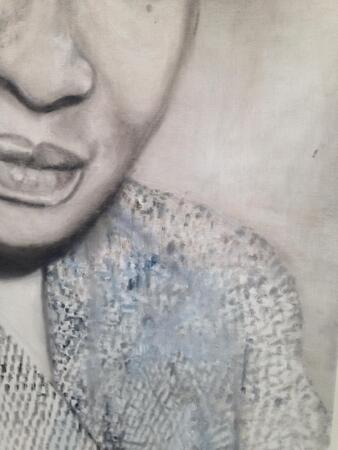

At first when I saw the huge portrait on the wall, I wasn't sure, I thought this artist's range is so great as to be almost incoherent, then I realized, two artists.

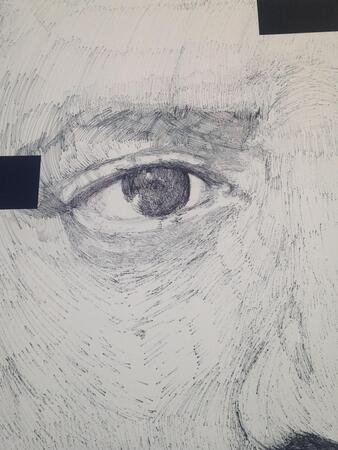

The wall-size portrait:

Here are details:

And an installation on three walls of seven portraits, which I did not photograph whole.

The faces, technique, movement, fullness.

Tracery and cloth related to the other half of the exhibition.

On the whole, the experience of these portraits so different from the one that had drawn me in, the architectural ships, that I had trouble making the adjustment. That seemed interesting.

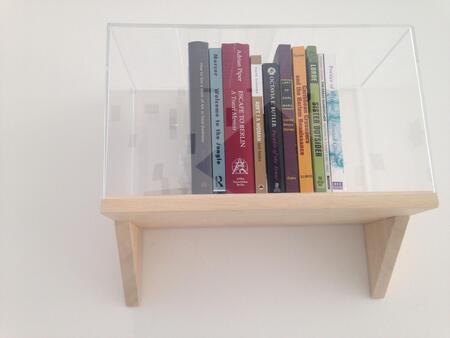

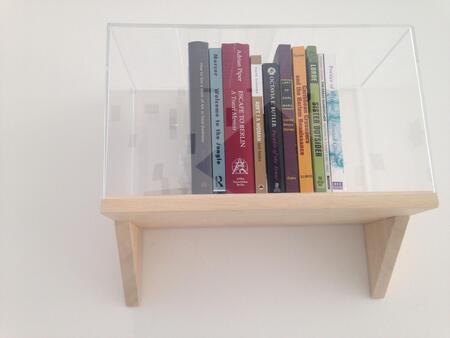

And rapidly, quick thoughts, conceptually – a wall of other artists’ exhibition installations, a small display of books in a glass case:

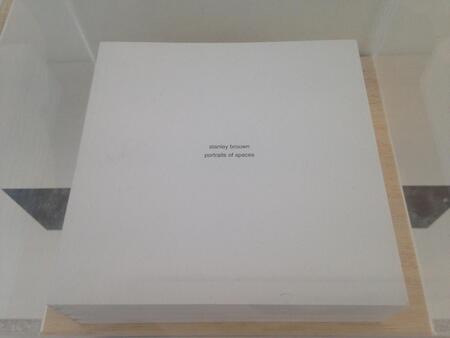

A book carefully encased, stanley brouwn, portraits of spaces.

This was it, then, the thing I was going to see and experience this day.

In the pavilion, I quickly glanced through the visitor guide – at the Biennale these are small pamphlet-catalogues, with essays, in this case by the two artists and the curator, and installation shots. I worked out that the titles of the whole was The Measurement of Presence. The artist of the structures was Remy Jungerman, and of the portraits iris Kensmil, the curator Benno Tempel. The pavilion announced itself as transnational. (At the Biennale, I understood, this was a significant political allegiance, there were those pavilions that accepted national, and often nationalist designations, those that resisted them.) It was not clear to me what national labels Jungerman and Kensmil might be given. Because Kensmil had painted many women whom I thought of as North American figures, I thought she might be North American. Because Jungerman used nails, as one of the texts in the pavilion explained, following how maroons in Suriname had used them in their cultural practices, I thought he had at least studied that tradition. There was something about New York, Amsterdam, there were notes of Mondrian and of stanley brouwn that seemed to run through the whole presentation.

I was deliberate, took impressions and pictures. When I came home, I showed my mother a few of the photos from this pavilion, and she was interested.

In the months since, I find I can call up the feeling of that space, those works. I feel greeted, given room. When I pass by the photos I took, scrolling to find a picture of the children, my mother, I nod in recognition, almost a hello.

*

When I taught the writing about the arts class that I teach every year this past fall, the fall of 2019, we had the practice I always use: during most sessions of the class, we cross the courtyard to the Smart Museum of Art, our college art museum, walk into the galleries, and a couple of the students present works they have chosen and considered to the class.

Last fall, several of the students chose to present works from the show that was up, Samson Young: Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me? Young’s work is complex and conceptual. The students had done a lot of research, and filled in a whole world of historical particulars that were referenced in the works. Listening to their presentations, I began to have a thought that interested me about sequence of experience in contemporary work.

In an earlier time, an artist would be making work for viewers who could be assumed to have certain knowledge, certain shared experiences – a point of view, cultural commonalities, connoisseurship. This was never entirely the case, there were always gaps, imaginations, intuitions, assumptions. But it held true enough. The viewer would bring what they had to bear at the time of seeing the work. A meaningful work would reverberate and stay with the viewer later, but a significant part, maybe even the bulk of the work of seeing would have been the work the viewer had done in the past, leading up to seeing the work.

Now, though, artists are working from frames of reference – personal, geopolitical, experiential – that are quite unlikely to be shared. A viewer comes from a position of much more ignorance of the relevant material and experience. There is still a shock and significance to the period of direct interaction with the work. But perhaps the bulk of the work of seeing is shifted forward. Into a period of consideration and research that will happen after seeing the work.

I had this thought watching the students filling out their knowledge and mine around Samson Young. The thought had another set of origins in the transnational pavilion curated by Benno Tempel of works by iris Kensmil and Remy Jungerman.

This morning, going through photos to begin a new entry, I passed a few pictures of the Jungerman structures and went to look for rest. There they were. And the pamphlet-catalogue, how happy I am now that I took one, kept it, through the next scrambled week of travel with the children, the getting home, the subsequent nine months of papers piled and sliding on my desk, and turned it up, just two days ago, and set it aside. Now I have read it through, for the first time, now I have looked up the websites of the artists, now I have read a little about the history and geography of that place on the continent that gets called South America where borders have been drawn to make the country that gets called Suriname. Tomorrow work can begin.