Hokusai Turned Sideways

Frederick Project: Colors and History

Saturday, March 21, 2020

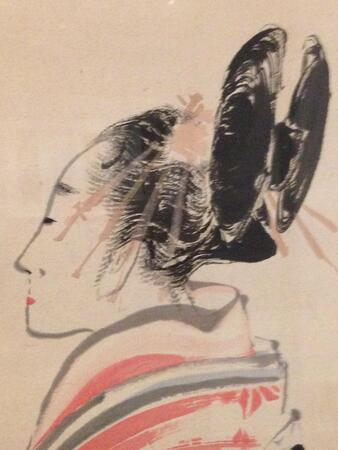

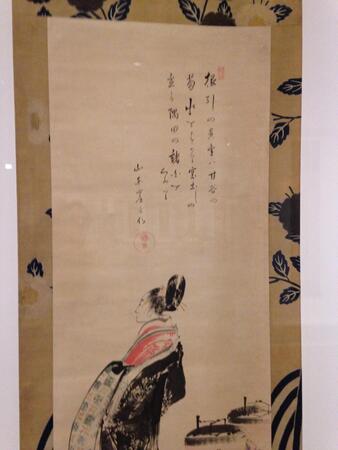

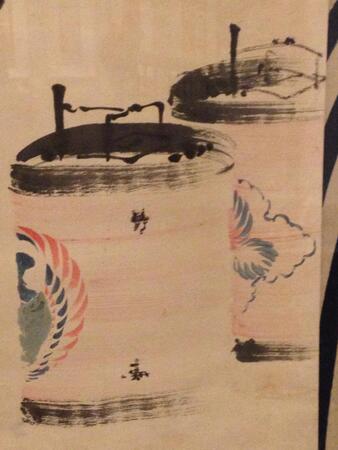

Katsushika Hokusai, Courtesan and Paper Lanterns, 1798/1800, the Weston Collection, Detail. Photos by Rachel Cohen

Because it was behind glass, I could only photograph it sidelong.

It came as a great relief. In the Art Institute of Chicago’s show of 2018, Painting the Floating World: Ukiyo-e Masterpieces from the Weston Collection. Room after room of courtesans – the highly-paid ones in their graceful rooms which they still could not leave unless a patron could be persuaded to purchase their contracts; and the ones who worked the docks at night, with stalls for quick transactions – all posed for a viewer’s eye, and, also, for my eye. The figures were very beautiful, and had a complicated agency, they had dressed themselves, were color artists of the first order, a few had written poems which were included, in their handwriting, what western nude had ever written on her canvas, still, there was a fundamental transaction, and it was wearying.

Then, Hokusai. She is turned sideways.

She is looking at something else, the air, her world.

If you look at her without her feet, the picture comes to pieces, so that her walking, her stepping forward on her own sandal is crucial to the understanding.

She is a whole being, and I can join in being her – feel a freedom in my thoughts when I try to think as her, all intelligence is possible – how is this conveyed?

The scroll is carefully mounted and framed by fabric, like the quilted edges of the Faith Ringgold story-quilts, and, like them, it is given an interpretation in language that is included. Above her hair, calligraphy:

Hokusai’s friend, Santo Kyoden (1761-1816), who frequently collaborated with him, has written the poem, which the Art Institute translated:

The wall text explained. Two kinds of wine. One, magical, the chrysanthemum waters, associated with the highly-paid and knowing courtesan, the oiran, who might be able to get a patron to purchase her release – gold for the release. But the novice courtesan, she had merely Sumida wines, from the Sumida river that runs by the Yoshiwara district, the red-light district of Edo. Constraint acknowledged.

Another liberty is the boldness of the brushwork.

And another in the way the scroll shows the night, it must be night. In the clothes and the lantern. Their black ink absorbs the night and radiates it.

The lanterns are made of the same paper that the scroll itself is painted on. They are upstanding, and let you think about paper, and how it can show the night.

The lanterns become one of the frames – like the fabric, like the poem – a way the picture can refer to itself. They are part of what gives the picture, and the woman in the picture, and me, looking at the picture, a first-person stance, freedom of mind.