Beauford Delaney and Ella Fitzgerald: In Yellow

Frederick Project: Abstract

Monday, March 23, 2020

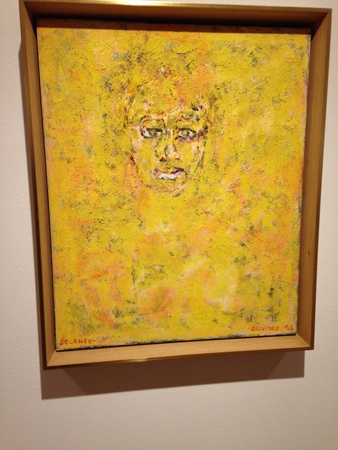

Beauford Delaney, Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald, 1968, oil on canvas, 24 x 19 1/2 inches, SCAD Museum of Art. Photos by Rachel Cohen.

In February, I went to a conference at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, organized by Amy J. Elias, called In a Speculative Light: The Arts of James Baldwin and Beauford Delaney. Some of the speakers were to give the first talks of their careers and others were people of great renown; all, feeling the significance of honoring the friendship between Baldwin and Delaney, and wanting to have the chance to give real attention to Delaney’s less studied work, had carefully prepared. We arrived at overlapping considerations, the conversation was layered, and had a quality of movement and return.

On the Saturday, we went our separate ways, and I went to the Knoxville Museum of Art (currently closed) and settled in to the exhibition: Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door. The curator, Stephen Wicks, kindly accompanied me through his beautiful show and to the storage facility. What I had heard in the previous days meant that I saw differently, and, indeed, I notice that all my looking since has been affected by the perspectives I absorbed in Knoxville. This entry is particularly indebted to Robert G. O’Meally, Zora Neale Hurston Professor of Comparative Literature at Columbia University, who concluded his presentation at the conference with a video clip of Ella Fitzgerald in live performance.

Here is a photo I took of Beauford Delaney’s portrait of Ella Fitzgerald from 1968; it usually lives in the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia (currently closed).

And here is the face, closer.

Looking at Delaney’s work, two questions that often come to mind are: How did he think about the relationship between portraits and abstractions? and How did he think about yellow? These are perennial not-fully-answerable questions.

These questions about Delaney have a history. They come up in the writing of James Baldwin about Delaney, and in the biographies that David Leeming, who knew both men well, wrote about Baldwin and Delaney. Both questions were central to one of the first important shows of Delaney’s work after his death, curated by Richard J. Powell, Beauford Delaney: The Color Yellow (2002), and they were considered again by the artist Glenn Ligon when he curated a show called Encounters and Collisions in 2014 and wrote a letter of elegy to Delaney on that occasion. The questions recur frequently in the compendium of writings Monique Wells keeps on the website Les Amis de Beauford Delaney.

It is often said, and is written on the SCAD Museum website entry for Delaney’s Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald, that yellow to Delaney meant “illumination and healing.” But I think there may be some difference in the yellows he uses when they run through and around a face, and when they are in one of the purely abstract paintings. When I look at the yellows in which there is a face, I often feel that I am squinting, that there are edges and injuries. It is a yellow connected to bodies, browns, roses, greens, not only to light and landscape.

Here the paint has a thick, opaque quality and intense brightness. I feel a sense of struggle, sometimes of blaze.

Delaney heard voices, and this condition worsened as he grew older. The voices were disturbing, and echoed the prejudice that Delaney, who was African-American and gay, experienced in the minutes and hours of his days. It was hard to tell whether the voices made sense or didn’t.

In inner life, abstraction partakes of sense and nonsense. This is part of how it can be near to difficulty and confusion, and also witty. Delaney was very witty. It may be that yellow is a color capable of holding these aspects of inner life together.

Delaney said he didn’t look at Ella Fitzgerald or pictures of her to make this painting, “just painted something I saw in my mind.”

He had listened to her many nights. He must have noticed the way the words “Ella” and “yellow” participate in one another.

Why did he sign the painting in this strange way – twice, or two halves, last name in one corner, first name and date in the other, taking himself apart? Is the painting also a self-portrait?

Turning all this over in mind, I went to listen to some of Ella Fitzgerald's most abstract singing, scat like some of what Robert O’Meally had played in Knoxville. Wit, abstraction, radical modernism, quotation, self-reference, edges, deliberate opacity, control of negative space, blaze.

This is One Note Samba, from 1969, the year after the portrait, live at the Montreux Jazz Festival. Ella Fitzgerald with Ed Thigpen on drums, Frank de la Rosa on bass, and Tommy Flanagan on piano.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PbL9vr4Q2LU