Faith Ringgold Story Quilts

Tuesday, May 5, 2020

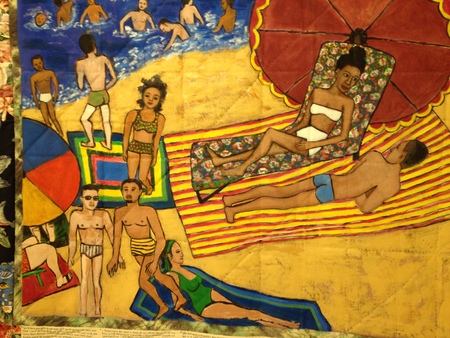

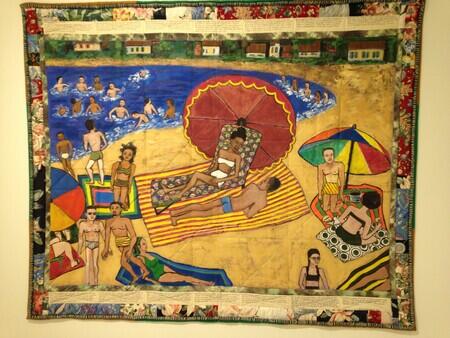

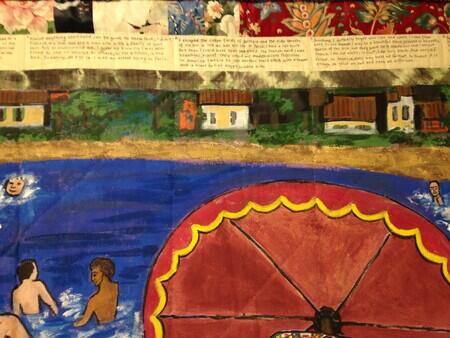

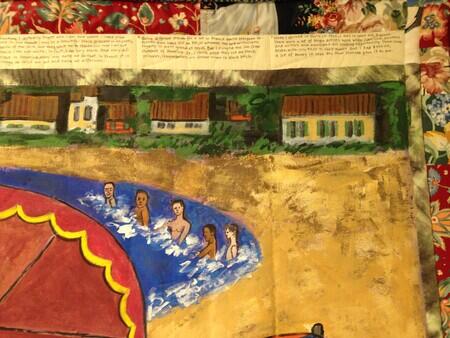

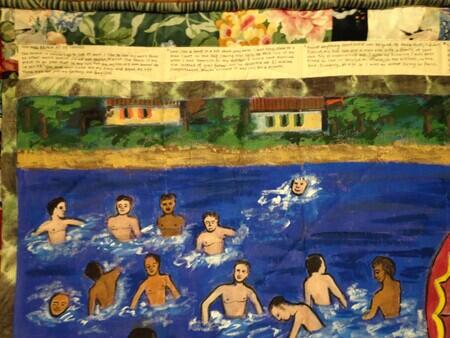

Faith Ringgold, On the Beach at St. Tropez, From the series, The French Collection, 1991. Collection of Patricia Blanchet and Ed Bradley. Detail photos Rachel Cohen.

“On the Beach at St. Tropez” was the first Faith Ringgold story quilt I’d seen, and I was completely unprepared for the encounter.

I was floored. And know what that expression means as I find it is the right one: it means my soul rushed down to the floor so that I could look up and take the measure of this.

I had already read the wall text, so I knew that there was a character, Willia Marie Simone, an African-American artist who had gone to Paris in the 1920s and had a wonderful, historically very nearly possible but not quite, life in art.

Willia Marie Simone had known Gertrude Stein and James Baldwin and other people in the Paris settings where I had also tried to depict Stein and Baldwin in my first book. I knew that territory of imagination well, and I had thought about different kinds of impersonation that may open in that vicinity.

I looked for a while at the color.

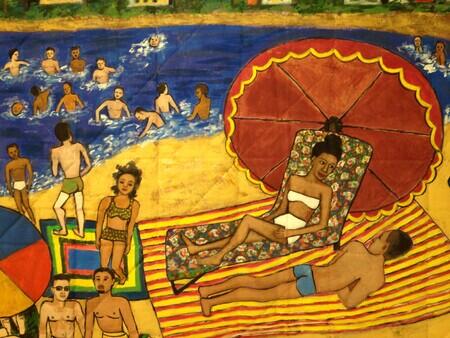

And then I began to read the words. And I laughed out. It was so funny, the tone. This character, her audacity, and self-involvement, the way she said absolutely true things and self-serving things and loving things and perceptive things and things ground out of economic and racial reality and how she seemed alive to people and their bodies.

I wrote about On the Beach at St. Tropez almost as soon as I started doing this project, this museums-are-closed-and-what-do-I-want-to-look-at-in-the-room-of-my-computer project. But the pictures I had taken weren’t sharp enough to show the text. I could find the wit in the swimmers' faces, the loungers' bodies, but the deliberateness I knew was there was hard to bring through.

A kind colleague from the Smart Museum, Berit Ness, saw my post and sent over a higher-resolution image. And I read the text eagerly. But then I couldn’t quite find the humor and boldness that had been so strong in my first impression.

I’ve read through it several times over the last six weeks. The closest I come to getting the impression back is when I scroll across the image with the words still in my mind. It was the impression of both together that gave the language its tone. Read with the painting, it’s a speaking voice. You are the child getting the letter, from this mother, yours, who sent you off to live with Aunt Melissa so that she could paint and go to the beach at St. Tropez, but who lives in this realm of vividness that is like no other thing in life, and you are also the knowing person in a museum who feels the inextinguishable rightness of this written personality, the slyness and tenderness of the faces and gestures here observed, and you can laugh.

Here is a kind of center of the story quilt. The text is numbered, and the passages below are 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

10 is at the base of a column of space with the central figure watching the young man lying below her, then under the woman in the green bathing suit lounging on blue towel.

I find the line breaks are important:

10. You are such a beautiful boy, my son, and if you want to judge

me it is your choice to do so. But it will only make us both

sad. I cannot change my past or yours. I abhor criticism. It is

so useless to be judged in your later years, when you have

no time to change. We must learn to change all that is amer

à doux, bitter to sweet.

*

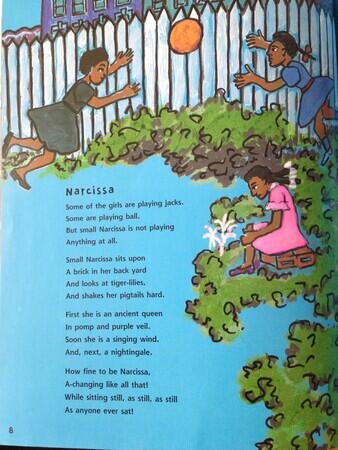

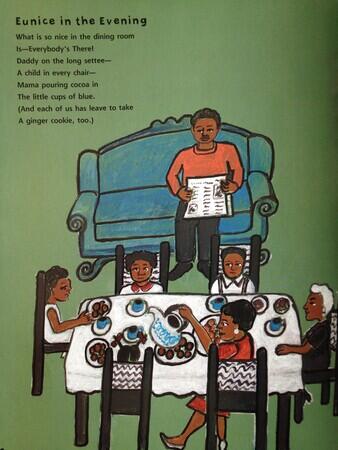

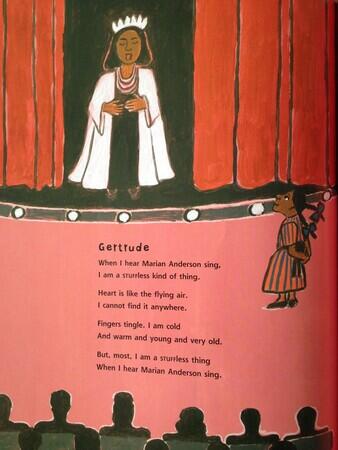

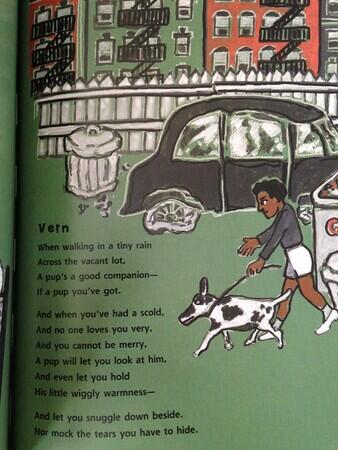

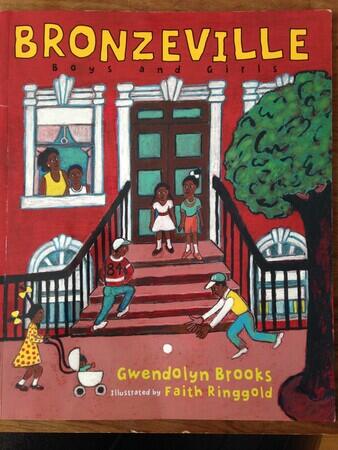

Not too long after we moved here, I bought, at the 57th Street Bookstore, a book of poems for children called Bronzeville Boys and Girls. The poems are by Gwendolyn Brooks. Each is about a child, and the title of the poem is the child’s name, and sometimes something about the child. “Narcissa,” “Vern,” “Robert, Who is Often a Stranger to Himself,” “Eunice in the Evening.”

It was only while we have been in shelter, and reading those poems again, that I realized that the illustrations in our book are part of a new edition from 2007, and were made by Faith Ringgold.

Since mid-March, every day, almost every day, that we are sheltering, one or the other of us takes the children and we walk to Gwendolyn Brooks Park, which is about six blocks away, and we look at the sculpture of her there by Margret McMahon, that McMahon made in close collaboration with Gwendolyn Brooks’s daughter Nora Brooks Blakely. Every day, I try to think about how to write about Gwendolyn Brooks. I do not know how to write about Gwendolyn Brooks.

Bronzeville Boys and Girls, words and paintings, is a masterpiece. Because of the Ringgolds, you may hear the voices in ways you didn’t expect. Tomorrow, I will try to think about the sounds of this.