Amélie Rorty In Memoriam

Thursday, September 24, 2020

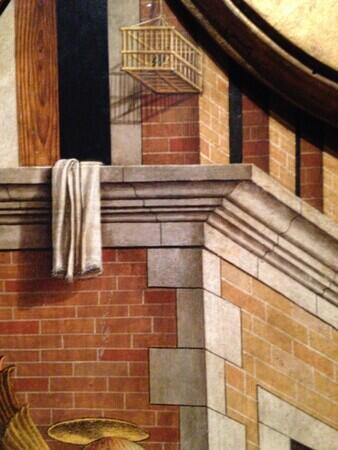

Carlo Crivelli, The Virgin Annunciate, 15th century, Staedel Museum, all detail photos Rachel Cohen

In Cambridge, we had a lovely friend, the philosopher Amélie Rorty. About five years ago, not too long before we left Cambridge, I went with Amélie to see this very beautiful show of the work of Carlo Crivelli (the 15th century Italian artist) at the Gardner Museum. We walked through the show gently, looking at each painting carefully and talking them over as she and I both loved to do. Amélie died last week, at the age of eighty-eight and, in my sorrow, I would like to write a small remembrance.

Amélie was a person of wide culture, a person of eagerness and curiosity, delightable, but with a clear-eyed sense of human failings and frailty. She loved a good sharp conversation and when people really got talking with vigor about matters intellectual, artistic, or political, her eyes would get full of light, and she would seem in her element, like an otter in a river. I sometimes would take a walk with her along the Charles River, and once or twice I went to eat at her apartment, which looked out over that river. We shared an interest in Jane Austen’s work, and I enjoyed testing out my latest thoughts against her quick, receptive, thorough-going knowledge and ready opinions. She was already in her eighties, but she walked steadily and intentionally; she held herself to a high standard.

**

Once she gave us an old-fashioned lamp that burned lamp oil; once a small red vase, of an unusual glaze with some brown in it – it sits in a nice place on a high shelf in our kitchen. These things are like her – illuminating, self-certain, hopeful but aware of darkness.

At the Crivelli show at the Gardner, we lingered in front of many paintings – it was very beautiful there, dark, and the paintings especially luminous. I thought I had taken pictures of many of the paintings, for I had come to have a great admiration for the graceful and powerful Crivelli of St. George and the Dragon in the Gardner’s collection, and this was a rare chance to see many together. But I also remember that I was trying to really concentrate and see with Amelie, and that photographing would have been a distraction. I seem only to have photographed two small panels, The Angel of the Annunciation and The Virgin Annunciate, both had originally been part of the same altarpiece and both belong to the collection of the Staedel Museum in Germany. I remember that Amélie and I both had an uplifted and gratified feeling about the exceptional perfection of Crivelli’s architectural sense.

Carlo Crivelli, The Angel of the Annunciation, 15th Century, Staedel Museum, all detail photos Rachel Cohen

**

Amélie was born Amélie Oksenberg, in Belgium, in 1932, the daughter of Polish Jews Klara and Israel Oksenberg; they emigrated to Virginia, where she grew up on a farm until she went to the University of Chicago, when she was, I think, about sixteen. Her recollections of the University of Chicago circa 1950 were very vivid – she was pleased by the fact that we came to teach here, and delighted and proud to let me know that her granddaughter now attends the University of Chicago. I had the impression in her recollections of a place of great intellectual ferment, formative for who she went on to be and what she went on to write about. There is a picture online of her sitting with a colleague, a young professor talking to another, together they look at a book by John Dewey, each holding it with one hand.

She got her graduate degrees in philosophy from Yale, and another master’s in anthropology from Princeton, she taught for twenty-six years at Rutgers, and those were very good years in her teaching life and she referred to them with great affection. During that time she was married to Richard Rorty and divorced from him – I never heard about him. Her kitchen was decorated with drawings her grandchildren had made. Once, when my husband and I, then childless, said something about our collective political and environmental life, which was then already worrying, though not yet as worrying as it has become, she said, I cannot be sanguine, I have hostages to the future.

I think the formation of the Depression and World War II never left her; she was a child of the 1930s and she thought hard about self-deception, ambivalence, and the erosion of moral conviction, but in surprising ways, not to cast blame, or to offer quick solutions, but as things to wonder over. Literature was very alive to her, and she found ideas about character, personhood, and presence in the Greek tragedians and in Dostoevsky. I often felt that I had a very incomplete grasp of her work and ideas and, searching around on the internet since I learned of her death, I find aspects of her thoughts that influenced others, and can feel how her thinking helped them on with own. Along with her own books, she was a great editor of volumes, and contributed several important collections where she brought together disparate voices on topics in moral philosophy and ethics.

I would not especially have associated her with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, but I will remember that they died on the same day, on September 18th of 2020, Rosh Hashanah, these two Jewish women who had lived through the same history – Ruth Bader Ginsburg was 87, Amélie Rorty was 88. A friend of mine sent around a note about Ginsburg that there is a belief among some Jews that people who were meant to die at some point during the previous year, if they are especially needed, will be held to die on Rosh Hashanah, the last possible day of that year.

**

After we moved away to Chicago, Amélie now and again sent me something Austen-related that she had come across and the last note I had from her, in July, was a message of congratulation about the publication of my book Austen Years. I wrote back, a good note, thank goodness, but I wish I had told her that she is thanked in its acknowledgements, which perhaps she didn’t know.

When I began keeping an art notebook online, in Cambridge, in about 2013, Amélie was one of the people who would regularly stop by and have a look around. Now and again she left a comment, and I am very glad that there are traces of her on these pages. Here is one she left after I had written about a few paintings by Cézanne and Degas that some inspired curators had temporarily hung together at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. In her words you can see, I think, how she thought about her own work as an editor in relation to that of curators, and you can see the way she thought about the sky that she spent a lot of time studying from the windows of her high apartment, and the way she thought about the people moving along on earth:

Thanks for these notes.

How much sky-blue there is in these paintings...Of course in Mme. Cezanne’s blouse, but also in the wall behind the Duchessa and in Degas's sister's blouse, her supercilious husband's tie... In a way, that blue is the hidden leit motif of these paintings, different as they are. The curators caught it, understood it, linked the paintings by painting the walls just that shade of blue...

Amélie