Louise Moillon Serendipity

Monday, September 21, 2020

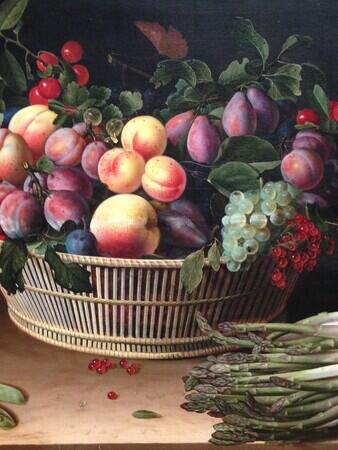

Louise Moillon, Still Life with a Basket of Fruit and a Bunch of Asparagus, 1630, Art Institute of Chicago. All photos Rachel Cohen.

Last week, on my first visit to the museum in six months, I saw a painting by an artist I don’t remember ever having heard of. This kind of serendipity is a special grace of museums.

When I teach writing about the arts each spring, I often teach an essay by Zbigniew Herbert called Still Life with a Bridle, about being arrested by an unknown painting, and from there beginning to discover its painter. Sometimes I teach Mark Doty’s slender book Still Life with Oysters, about falling in love with a Dutch still life one day at the Metropolitan Museum. It is interesting that both of these poets’ essays are ignited by a still life with a dark background made in the strained and brilliant 17th century by a Netherlandish painter.

Louise Moillon (1610-1696) is identified as French and her name sounds French, but her family were Calvinists from the Southern Netherlands. They lived in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood of Paris, which was where Protestants fleeing persecution took refuge in the time when France still sheltered them. Her father was a painter, from whom she learned the basics of painting in the family workshop, as did one of her brother's, Isaac Moillon, also a painter. After the father died, the mother, herself the daughter of a goldsmith, another highly trained artistic profession, married another painter, and this stepfather then ran the family workshop and supported Louise Moillon in becoming a painter. She was one of the most recognized French still life painters of her time, collected by King Charles I of England, and at least four of her paintings are in the Louvre.

This painting is in its own kind of exile from its origins.

Now that I know how to place her, I have a hundred thoughts – about the inventions of these works, and their deliberately slightly distinguishing the space in which each element hangs; about the fact that she was one of the two French painters to begin mixing still lifes with figure painting; about the way her paintings, aglow before their dark backgrounds would have looked to Chardin when he saw them, as he surely would have, and as he made his own experiments in the combining of domestic life with still life; about Moillon painting less after she married, then returning to painting when she was in her sixties; about her ceasing to paint altogether after France issued the edict of Nantes in 1685, which forced two of her grown children to flee to England, and possibly resulted in her husband going to prison; about her being given a Catholic burial when she died at eighty-six in 1696.

All of this will be good to think about. Right now, let me store the first impressions, the way they sang out across the room last Monday.

Look at this.

At this.

At this.