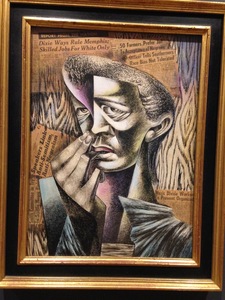

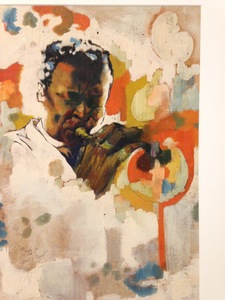

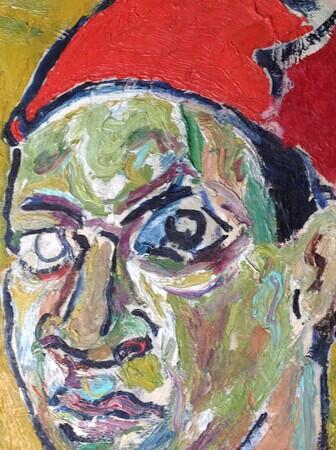

Delaney, Self-Portrait with a Red Hat

Thursday, June 4, 2020

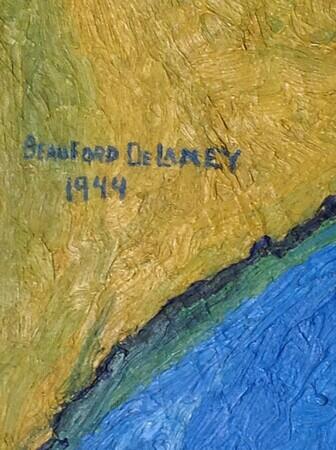

Beauford Delaney, Self-Portrait, 1944, Art Institute of Chicago. All photos Rachel Cohen.

Today, I just want to look at this self-portrait by Beauford Delaney, carefully, and from different distances.

It was painted in 1944. Yesterday, I was writing about 1943 – the year when the Harlem insurrection broke out on the night after James Baldwin’s father’s funeral, which was also the day of Baldwin’s 19th birthday. When Beauford Delaney found the money to pay for the father’s burial, and Baldwin drove through the streets of shattered glass to the burial. And then left Harlem and moved down to the Village to live with Delaney for a while until he got on his feet.

In other words, this painting is a part of the conversation Beauford Delaney was having with himself in 1944, after those events, when Baldwin was living nearby, and they were often at Connie’s Calypso, the restaurant, and spending their time with musicians, and listening to records on Delaney’s Victrola. It was 1944; more than one and half million African-American people were serving in the US armed forces by the end of the war in 1945, and Jim Crow was still in full force on the home front.

What is self-regard?

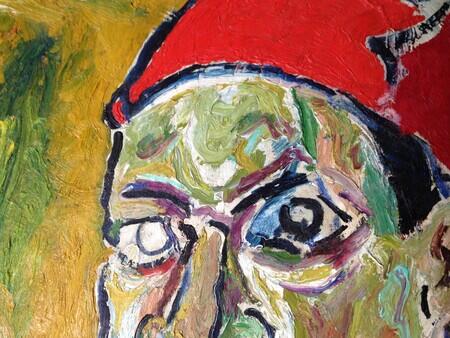

The day I visited with this painting, in the storage basement at the Art Institute of Chicago, I was not alone. The woman who arranged my visit and sat on a broken chair in the background while I looked was Julie Warchol, Collection and Exhibitions Manager. She kindly brought out and turned on a conservation lamp, so that I could really see. This means that I got better pictures than even a museum can take, because, in Delaney, the paint is so thick that it really casts shadows, which your eye sees right away, but most photographs don’t show. It is a little bit as if you are looking at a sculpture made of paint.

I think it may be easier to intuit relationships between sculpture and music than it is between painting and music. Music has a spatialness, and you move around in it, backwards and forwards and looping in time the way you walk around a sculpture.

The sculptured paint seems to have special significance around what looks like a scar at the figure's neck. Some art historians think this was a place where Delaney changed the proportions of the figure. Others imagine this as a more direct comment on history and its violence.

Delaney often let the canvas show through here and there, and those places are generally important. Cézanne did this, too, and we know that Delaney spent a lot of time thinking about Cézanne. These spaces are material and sculptural. You can see the canvas and the weave, with its implicit gaps, and it also makes you aware of how thin or thick the paint may be.

**

Before I had spent significant time in the presence of Delaney paintings, I think I would not have said that he is a painter in whom one feels geometry, as one feels it in the Florentine painters, in Poussin, and in Cézanne. But if you are actually standing with these paintings and staying open to them, then you do feel geometry. I think it is an interesting thing about the racialized education I go on receiving that I had assumed, without having really seen any paintings by Delaney, having seen only reproductions, that Delaney was an abstract painter who moved by color that was – and I know this is crazy – somehow divorced from space and spatial considerations.

Why would I think that a Black painter wouldn’t work from a theoretical sense of space?

It’s in my own assumptions, but I think it’s also in the photographs of Delaney’s paintings. We know that photographs are not without bias, and that the flattening of photography reduces our understanding of painting’s intentions, but I think probably many works by people of color, even the ones that are in the museums, even the ones that have been photographed a million times, will need to be re-photographed by photographers who believe that the artists are working from a place of intense abstract awareness before art critics and art historians, working necessarily from reproductions, will be able to give the works their due.

**

There are several different ways that the red hat in this painting is Florentine.

This morning, I went to look at my pictures, and I remembered that in looking at the painting, I thought that red mattered a lot, the reds of the hat, and the way they bring out other reds, red was being used, very intentionally, to make a certain kind of space. I got that far in the presence of the painting.

Then, this morning, I thought that the range of reds in this Delaney know about Florentine spatialization – of a kind I was trying to write about here last week in thinking about Michelangelo’s red chalk drawing of staircases. And I searched for Florentine portraits in red hats. The most famous one in America is Youth in a Hat that used to be attributed to Botticelli and still sometimes is, though the National Gallery now gives the painting to Filippino Lippi, who studied with Botticelli after his own father, the renowned painter Filippo Lippi, had died.

Filippino Lippi, Youth in a Hat, c. 1485. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Museum website image.

I got the kind of chill that researchers get as a significant connection emerges. For this painting entered an American collection with huge fanfare in 1937 when Andrew Mellon purchased it to be part of his unprecedented gift of paintings to form the National Gallery of Art, a gift that was covered extensively in newspapers in 1937. The core of the National Gallery was built over the next few years, and was opened with a dedicatory ceremony in 1941, at which President Roosevelt said, as was widely quoted in the newspapers:

“The dedication of this Gallery to a living past, and to a greater and more richly living future, is the measure of the earnestness of our intention: that the freedom of the human spirit shall go on.”

At the moment, it's a speculation, but it would be interesting if the notes could be found to fill in Delaney's relationship to the paintings at the National Gallery. We know he went repeatedly to visit Isabella Stewart Gardner's collection, admired Gardner, and can presume that he was interested in the Gardner's rich holdings in Italian art of this period.

**

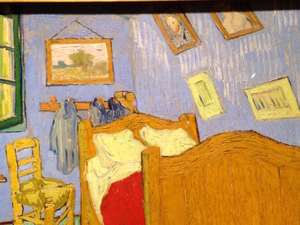

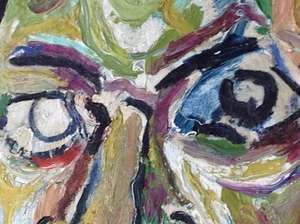

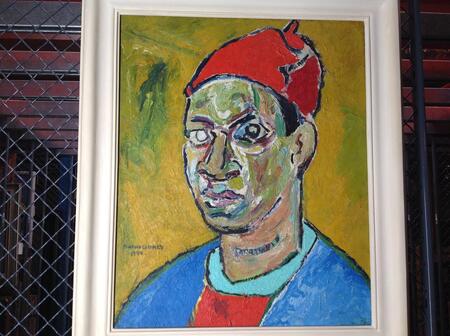

Look at these two photographs:

My photograph of the Delaney is an awkward photograph, but a true one, of the storage space, and includes the white frame, which I don’t know the history of, but which very much underscores the relationship to the white frame that Filippino Lippi painted right into the portrait he made. I haven't seen the Lippi in person, but, even in reproduction, Delaney's formal and painterly innnovations open a conversation between me and the painting that I cannot begin with the Lippi.

The geometry of the Lippis and of Botticelli was the geometry of the wave, the undulant line. And it is in part the uneasy relationship between their windy watery world and the perspectival geometry of their city that places them among the very queerest painters of the many queer Florentine schools.

I think I see a clue in the hat. To me, the line in Delaney’s hat, here it is upside down so the shape is as clear as possible, is related to the indented shape of the hairline of the youth in a hat:

**

The confidence of Delaney’s painting. This self-portrait is like Rembrandt doing his self-portrait as Titian’s Man With a Quilted Sleeve.

Some day, there will be a new, earnest dedication, to a greater and more richly living future. Perhaps a curator will imagine a show in which these two paintings will hang together, and the people who come to see them will be as open as Delaney himself was in 1944, and they will just walk up the hill to look out from the high place, these eyes that will be windows on to whatever that world will be.