Sargent

Feeling the Air, I

Tuesday, December 3, 2013

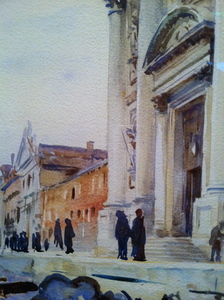

Sargent, Santa Maria della Salute, 1904

I’ve had a few conversations recently with people who are not that interested in painting. They say, reasonably, that in museums they are overwhelmed by the profusion, or that only really contemporary painting is strange enough to compel their attention, or that in front of paintings long and loudly admired their eyes feel veiled by expectations and history.

It feels odd to say in the face of these large and genuine concerns that when I am at a museum I am often merely after a small, fine sensation. The movement of light and air. That’s all. I know this feeling is of a family of quite ordinary feelings – on a good day one may have something like it walking to the grocery store. But, though common in life, it is rare in art. In very great literature, “But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?” But not, for example, in photography. It might be almost a definition of what distinguishes painting from photography that one does not feel the movement of the air in looking at photographs. Even in front of Ansel Adams, what one feels is majesty, not air. But in front of a painting the movement of light and air have held someone else’s attention in a way that lets me feel it and at the same time know myself to be feeling it.

The presence of the Sargent watercolors in Boston this season has focused my attention on how it is that painters offer this sensation to us. Why, looking at Sargent’s quick-stroked boats along the edge of a Venetian canal do I suddenly feel the soft air?

My guess is that this sensation is one of the aspects of seeing paintings in person that cannot be rendered in iphone details, but I’m going to try to illustrate what seem to me to be two sides of the answer.

It seems first of all to have to do with things jostling and overlapping. The two gondolas to the right here are at rest, but must be bumping each other. The figures standing on the stone are, in action, distinct but are shown overlapped by the long greenish boom of a boat, and the figures themselves and their shadows bleed into one another.

Boats, water, Venice, all ideal for this because it is not in any of their natures to be still.

We know the light reflected on the underside of the bridge to be dancing, as are the waves given in motion below. Jostling, overlapping, playing over, this gives the sense of motion, permeability, change, within the picture.

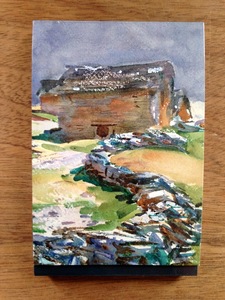

On the other side, the angle and motion of the viewer are also significant. Look at these two shots, almost identical of Portuguese Boats. I think that the sense of motion comes across better in the photo to the left, taken at a slightly stronger angle, then in the flatter front-on one to the right, in any case, shifting rapidly between the two may give something of the sensation.

The shift makes a small suggestion of how one sees the picture as one is oneself in motion. Of course when you see a painting in person you cannot help but move in front of it, if only to walk up to it. The spatial experience of a photograph changes much less as you move around in relation to it. I suppose because of the fixed position of the camera. The painter is constantly moving around in relation to her canvas and constantly changing the perspective. It must be the sense that space is changing around you that you have when you walk to the grocery store.

It feels odd to say in the face of these large and genuine concerns that when I am at a museum I am often merely after a small, fine sensation. The movement of light and air. That’s all. I know this feeling is of a family of quite ordinary feelings – on a good day one may have something like it walking to the grocery store. But, though common in life, it is rare in art. In very great literature, “But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?” But not, for example, in photography. It might be almost a definition of what distinguishes painting from photography that one does not feel the movement of the air in looking at photographs. Even in front of Ansel Adams, what one feels is majesty, not air. But in front of a painting the movement of light and air have held someone else’s attention in a way that lets me feel it and at the same time know myself to be feeling it.

The presence of the Sargent watercolors in Boston this season has focused my attention on how it is that painters offer this sensation to us. Why, looking at Sargent’s quick-stroked boats along the edge of a Venetian canal do I suddenly feel the soft air?

My guess is that this sensation is one of the aspects of seeing paintings in person that cannot be rendered in iphone details, but I’m going to try to illustrate what seem to me to be two sides of the answer.

It seems first of all to have to do with things jostling and overlapping. The two gondolas to the right here are at rest, but must be bumping each other. The figures standing on the stone are, in action, distinct but are shown overlapped by the long greenish boom of a boat, and the figures themselves and their shadows bleed into one another.

Boats, water, Venice, all ideal for this because it is not in any of their natures to be still.

We know the light reflected on the underside of the bridge to be dancing, as are the waves given in motion below. Jostling, overlapping, playing over, this gives the sense of motion, permeability, change, within the picture.

On the other side, the angle and motion of the viewer are also significant. Look at these two shots, almost identical of Portuguese Boats. I think that the sense of motion comes across better in the photo to the left, taken at a slightly stronger angle, then in the flatter front-on one to the right, in any case, shifting rapidly between the two may give something of the sensation.

The shift makes a small suggestion of how one sees the picture as one is oneself in motion. Of course when you see a painting in person you cannot help but move in front of it, if only to walk up to it. The spatial experience of a photograph changes much less as you move around in relation to it. I suppose because of the fixed position of the camera. The painter is constantly moving around in relation to her canvas and constantly changing the perspective. It must be the sense that space is changing around you that you have when you walk to the grocery store.