Sargent

Open to the Public

Sunday, November 17, 2013

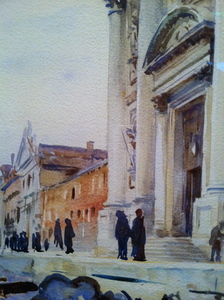

Sargent, I Gesuati, about 1909, iphone detail

Last Friday at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum I had a notion of looking for her Sargents, to keep company with the sense of the artist developing in my mind because of the watercolor show at the MFA. On entering the Gardner I must have half-noticed a small poster with a Venetian-looking Sargent on it, but this didn’t entirely register. I went first to the new wing to look at the Sophie Calle show Last Seen, about the great theft of pictures from the Gardner in 1990.

This show I liked very much. Simple, a photograph of a person standing in front of an empty frame, next to it, in the same size and shape as the frame, a series of short quotations from different people about the missing work. Some from interviews done at the time of the theft, a more recent group done now, about the empty spaces twenty-three years on. The show had a kind of intimacy with the paintings, especially in those quotations about the missing pictures that clearly came from the guards. One, speaking of a little Rembrandt self-portrait etching, a piece that had been stolen before, said that she (or he) always felt a little extra protective of that one, “I would just give it a little look as I went by.”

I went down the bright Renzo Piano stairs and into the dim museum Gardner designed herself to look for the Sargents. In the first of the small dark rooms containing the flotsam and jetsam of sketches done by Gardner’s acquaintances lowers one great brooding Manet of his mother. In the second little room, there should have been the Sargent watercolor of Gardner wrapped in white, the last portrait of her before she died.

I asked the guard about the sketch’s whereabouts. He was large, friendly, Russian, too friendly, he had already accosted me about a daub with orange flowers, and made me guess who had drawn an awkward sketch of a dancer. I said had the portrait gone to the MFA show, though I knew that was unlikely since the Gardner cannot lend or borrow. No, he said grandly, “it is in our show.” A little group, in the space beyond Mme Manet.

Eight, and the four on the left wall of Venice, and each of those four as good as the best on display across the Fens. Brilliant, improvisatory, dedicated, and, as I looked, a sudden lift, each one in turn seemed to give the air and moisture of Venice, I was in the city, felt it.

I had been careful at the MFA, but it was always so crowded in the first room of the watercolors of Venice that in the end I hadn’t needed the protection. They were just beautiful quick images, I didn’t have to think of our trip to Venice earlier this year and of scattering my father’s ashes there as he had asked. At the MFA I had noticed, admired, walked on.

But here at the Gardner, suddenly, taken by surprise, there is was, Venice. And then I longed to be there, and to think of my Dad. I would try to take down what Sargent had done to transport in this way. No photographs in the Gardner, of course, so I thought I would sketch his sketches.

I had just done the first, boats riding at anchor with the great church behind when another guard interrupted me. “I’m sorry, miss, no pen is allowed,” and he proffered a dull pencil, bitten or broken in half. “I forgot,” I said pleasantly, and, still determined, set to work to do the others in pencil. Of course it was much less fluid, and without ink couldn’t approximate the vivid feeling of looking, but I got some of the shadows. Another guard had come in and begun to talk in a loud voice to the one who had given me the pencil. I was midway through the third image, of a low bridge over the water, when it became impossible to pretend that my concentration had not been destroyed by his insistent story, about a man who had deliberately put his face too near the crotch of a boy, and the boy’s reaction. I glared to little effect, finished my sketches for form’s sake, and tried to return the pencil on departing, “you may keep it,” the guard said magnanimously….

I went up to the top floor, to see Sargent’s full-length oil portrait of Mrs. Gardner. It was her fault, anyway, all of these ridiculous regulations, no photos, no pen, even sketching made almost impossible, these hovering, intrusive guards. I’ve liked the stories of the early days of her museum, how shocked she was by souvenir hunters (and it’s true one lady did take our her scissors and try to take home a swatch of tapestry) and by teachers lecturing students, and by, worst of all, reporters, and how difficult she made it for the public to attend the museum that she intended to offer to that same public. So difficult that in the end she was charged all the back taxes she had avoided by claiming that her art imports were for the public good. This was all amusing enough, I thought to myself, mounting the staircases, but even a century later the place was still uncertain about just how open to the public it intended to be.

She presides in Sargent’s portrait, and there is a glad welcome in the figure – “you’ve come, you’ve come all the way up,” she says, and is pleased. What if they’d taken that picture? I thought I would go down again, and try to see the Venice my Dad loved and had left himself to.

There was no one in the little alcove when I entered. I had stood for a few seconds, thought I detected the first slight trembling, and through the door barreled the large Russian guard, waving his arms. As he came up to me, much too close, I said, frigidly, “I really would like to look at these pictures by myself, please.” He sealed up his mouth but waved energetically behind me. Yes, I said, I had seen the one of Mrs. Gardner. He nodded and walked away. Of course that finished it. Had I been rude, probably I had been rude. The openness I had to the pictures was gone. I went and found the man, thanked him again for his help; he hardly nodded.

I left the Gardner.

And went across to the MFA, and went down to see the Sargents. No one advised me, no one interrupted me, no one cared how I looked at the watercolors. One of which was almost an identical view of I Gesuati that had seemed so evanescent at Mrs. Gardner’s. I can reproduce it here:

The pale yellow wash of the façade, the beautiful dark blue and gray details. But the one at Mrs. Gardner’s, without passersby, with a more steep angle of the water and stone wall, was undeniably more dramatic, more empty. I had thought of my father, walking there.

How do the dead come and go in the places to which they have left themselves?

Sophie Calle had asked a medium to come and look at the empty frames in the Gardner. The medium had felt joy, felt that the spirit of the paintings was now diffused through the whole museum, and that the frames were open to possibility as they hadn’t been when they contained the paintings themselves.

I do not know how long it takes to come to the point where we do not wish our dead back on the actual earth with the air playing over their living faces, but I am not there yet. I want the paintings back.

This show I liked very much. Simple, a photograph of a person standing in front of an empty frame, next to it, in the same size and shape as the frame, a series of short quotations from different people about the missing work. Some from interviews done at the time of the theft, a more recent group done now, about the empty spaces twenty-three years on. The show had a kind of intimacy with the paintings, especially in those quotations about the missing pictures that clearly came from the guards. One, speaking of a little Rembrandt self-portrait etching, a piece that had been stolen before, said that she (or he) always felt a little extra protective of that one, “I would just give it a little look as I went by.”

I went down the bright Renzo Piano stairs and into the dim museum Gardner designed herself to look for the Sargents. In the first of the small dark rooms containing the flotsam and jetsam of sketches done by Gardner’s acquaintances lowers one great brooding Manet of his mother. In the second little room, there should have been the Sargent watercolor of Gardner wrapped in white, the last portrait of her before she died.

I asked the guard about the sketch’s whereabouts. He was large, friendly, Russian, too friendly, he had already accosted me about a daub with orange flowers, and made me guess who had drawn an awkward sketch of a dancer. I said had the portrait gone to the MFA show, though I knew that was unlikely since the Gardner cannot lend or borrow. No, he said grandly, “it is in our show.” A little group, in the space beyond Mme Manet.

Eight, and the four on the left wall of Venice, and each of those four as good as the best on display across the Fens. Brilliant, improvisatory, dedicated, and, as I looked, a sudden lift, each one in turn seemed to give the air and moisture of Venice, I was in the city, felt it.

I had been careful at the MFA, but it was always so crowded in the first room of the watercolors of Venice that in the end I hadn’t needed the protection. They were just beautiful quick images, I didn’t have to think of our trip to Venice earlier this year and of scattering my father’s ashes there as he had asked. At the MFA I had noticed, admired, walked on.

But here at the Gardner, suddenly, taken by surprise, there is was, Venice. And then I longed to be there, and to think of my Dad. I would try to take down what Sargent had done to transport in this way. No photographs in the Gardner, of course, so I thought I would sketch his sketches.

I had just done the first, boats riding at anchor with the great church behind when another guard interrupted me. “I’m sorry, miss, no pen is allowed,” and he proffered a dull pencil, bitten or broken in half. “I forgot,” I said pleasantly, and, still determined, set to work to do the others in pencil. Of course it was much less fluid, and without ink couldn’t approximate the vivid feeling of looking, but I got some of the shadows. Another guard had come in and begun to talk in a loud voice to the one who had given me the pencil. I was midway through the third image, of a low bridge over the water, when it became impossible to pretend that my concentration had not been destroyed by his insistent story, about a man who had deliberately put his face too near the crotch of a boy, and the boy’s reaction. I glared to little effect, finished my sketches for form’s sake, and tried to return the pencil on departing, “you may keep it,” the guard said magnanimously….

I went up to the top floor, to see Sargent’s full-length oil portrait of Mrs. Gardner. It was her fault, anyway, all of these ridiculous regulations, no photos, no pen, even sketching made almost impossible, these hovering, intrusive guards. I’ve liked the stories of the early days of her museum, how shocked she was by souvenir hunters (and it’s true one lady did take our her scissors and try to take home a swatch of tapestry) and by teachers lecturing students, and by, worst of all, reporters, and how difficult she made it for the public to attend the museum that she intended to offer to that same public. So difficult that in the end she was charged all the back taxes she had avoided by claiming that her art imports were for the public good. This was all amusing enough, I thought to myself, mounting the staircases, but even a century later the place was still uncertain about just how open to the public it intended to be.

She presides in Sargent’s portrait, and there is a glad welcome in the figure – “you’ve come, you’ve come all the way up,” she says, and is pleased. What if they’d taken that picture? I thought I would go down again, and try to see the Venice my Dad loved and had left himself to.

There was no one in the little alcove when I entered. I had stood for a few seconds, thought I detected the first slight trembling, and through the door barreled the large Russian guard, waving his arms. As he came up to me, much too close, I said, frigidly, “I really would like to look at these pictures by myself, please.” He sealed up his mouth but waved energetically behind me. Yes, I said, I had seen the one of Mrs. Gardner. He nodded and walked away. Of course that finished it. Had I been rude, probably I had been rude. The openness I had to the pictures was gone. I went and found the man, thanked him again for his help; he hardly nodded.

I left the Gardner.

And went across to the MFA, and went down to see the Sargents. No one advised me, no one interrupted me, no one cared how I looked at the watercolors. One of which was almost an identical view of I Gesuati that had seemed so evanescent at Mrs. Gardner’s. I can reproduce it here:

The pale yellow wash of the façade, the beautiful dark blue and gray details. But the one at Mrs. Gardner’s, without passersby, with a more steep angle of the water and stone wall, was undeniably more dramatic, more empty. I had thought of my father, walking there.

How do the dead come and go in the places to which they have left themselves?

Sophie Calle had asked a medium to come and look at the empty frames in the Gardner. The medium had felt joy, felt that the spirit of the paintings was now diffused through the whole museum, and that the frames were open to possibility as they hadn’t been when they contained the paintings themselves.

I do not know how long it takes to come to the point where we do not wish our dead back on the actual earth with the air playing over their living faces, but I am not there yet. I want the paintings back.