Morisot

Private Collection II (with Paul Valéry)

Monday, June 3, 2013

Some weeks later I remembered that I had read something about Berthe Morisot, long ago, in a book by Paul Valéry, a collection of occasional pieces about painting with the somewhat misleading title Degas, Manet, Morisot. I hurried back to read the passages on Morisot, three really, altogether perhaps ten pages.

The man who wrote the introduction to the volume decided, rather ruefully, that, despite living among the Impressionists and being himself so intelligent, Valéry’s writing about them was only in a limited way perceptive. The poet seems in a way to take the painters and their achievements for granted. But, for me, these few passages, coming as they do from a man who was married to one of Morisot’s nieces, and lived in the house that had been Morisot’s, offer something more than useful about “Tante Berthe.” Morisot’s daughter and her cousins had grown up surrounded by paintings: Morisot’s and also those of their close friends – Renoir, Degas, Monet. Berthe Morisot was Berthe Manet, as she was married to Édouard Manet’s brother, Eugène. I’ve read Morisot’s correspondence with Stephane Mallarmé now, too, and the letters give the impression of life intensively lived among a few choice acquaintances. “Rare and reserved,” Valéry says; the work, too, is private.

Of all the artists he encountered, Valéry weighed it out, Morisot, he thought, was the one:

to live her painting and to paint her life, as if the interchange between seeing and rendering, between the light and her creative will, were to her a natural function, a necessary part of daily life. It is this which gives her works the very particular charm of a close and almost indissoluble relationship between the artist’s ideals and the intimate details of her life. Her sketches and paintings keep closely in step with her development as a girl, wife, and mother. I am tempted to say that her work as a whole is like the diary of a woman who uses color and line as her means of expression. (119)

This might be a subtle way of dismissing a woman’s work – another woman damned with praise for her understanding of the quotidian – but it doesn’t strike my ear that way. Valéry also says of her canvases:

Made up of nothing, they multiply that nothing, a suspicion of mist or of swans, with a supreme tactile art, the skill of a rush that scarcely feathers the surface. But that featheriness conveys all: the time, place, and season, the expertise and swiftness it brings, the great gift for seizing on the essential, for reducing matter to a minimum and thus giving the strongest possible impression of an act of mind…. (121)

The surprising texture of paint in her handling, the odd inward structure of the material, these phrases of Valéry’s, give something to think about.

Landscape of La Creuse, 1882, Private Collection.

Woman Hanging Out the Wash, 1881, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

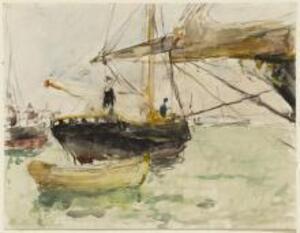

Young Woman in a Rowboat, Eventail, 1880, Private Collection.

Citations from: Valéry, Paul, Degas, Manet, Morisot. Translated by David Paul. Edited by Jackson Matthews. With an Introduction by Douglas Cooper. Princeton University Press: 1960.

Paintings: see the Athenaeum.

The man who wrote the introduction to the volume decided, rather ruefully, that, despite living among the Impressionists and being himself so intelligent, Valéry’s writing about them was only in a limited way perceptive. The poet seems in a way to take the painters and their achievements for granted. But, for me, these few passages, coming as they do from a man who was married to one of Morisot’s nieces, and lived in the house that had been Morisot’s, offer something more than useful about “Tante Berthe.” Morisot’s daughter and her cousins had grown up surrounded by paintings: Morisot’s and also those of their close friends – Renoir, Degas, Monet. Berthe Morisot was Berthe Manet, as she was married to Édouard Manet’s brother, Eugène. I’ve read Morisot’s correspondence with Stephane Mallarmé now, too, and the letters give the impression of life intensively lived among a few choice acquaintances. “Rare and reserved,” Valéry says; the work, too, is private.

Of all the artists he encountered, Valéry weighed it out, Morisot, he thought, was the one:

to live her painting and to paint her life, as if the interchange between seeing and rendering, between the light and her creative will, were to her a natural function, a necessary part of daily life. It is this which gives her works the very particular charm of a close and almost indissoluble relationship between the artist’s ideals and the intimate details of her life. Her sketches and paintings keep closely in step with her development as a girl, wife, and mother. I am tempted to say that her work as a whole is like the diary of a woman who uses color and line as her means of expression. (119)

This might be a subtle way of dismissing a woman’s work – another woman damned with praise for her understanding of the quotidian – but it doesn’t strike my ear that way. Valéry also says of her canvases:

Made up of nothing, they multiply that nothing, a suspicion of mist or of swans, with a supreme tactile art, the skill of a rush that scarcely feathers the surface. But that featheriness conveys all: the time, place, and season, the expertise and swiftness it brings, the great gift for seizing on the essential, for reducing matter to a minimum and thus giving the strongest possible impression of an act of mind…. (121)

The surprising texture of paint in her handling, the odd inward structure of the material, these phrases of Valéry’s, give something to think about.

Landscape of La Creuse, 1882, Private Collection.

Woman Hanging Out the Wash, 1881, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Young Woman in a Rowboat, Eventail, 1880, Private Collection.

Citations from: Valéry, Paul, Degas, Manet, Morisot. Translated by David Paul. Edited by Jackson Matthews. With an Introduction by Douglas Cooper. Princeton University Press: 1960.

Paintings: see the Athenaeum.