Degas

A little further with Degas

Sunday, August 3, 2014

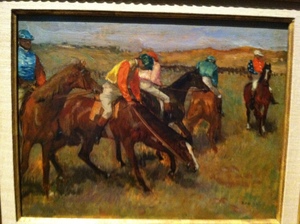

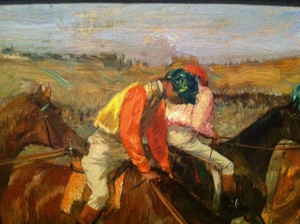

Edgar Degas, Before the Race, The Clark Museum, c.1882

Many of Degas’ paintings and drawings of racehorses have titles that name the same moment. The one at the Clark Museum is called “Before the Race.” Degas, we are often told, wanted to capture the feeling of motion in painting. The moments before a horserace are astonishingly dense with motion, not the wild free motion of the race, but the expectation of it. I think people who love races love the combination – before and during – the anticipatory pausing steps, a taut potential that then gallops free. Great paintings work continually along the tense edge between stillness and motion, and painting seems well-suited to giving the hesitating about-to-be-motion that comes before.

At the Clark, “Before the Race” caught all of our attention. Little S., two, likes animals in pictures. M. and I also found ourselves momentarily absorbed in the little picture, the elegant animals, the bright-silked riders. We never know how long we have in a gallery and I hurried to document what my eye seemed to be noticing. Here are my six details, in the order taken:

It was only in looking at the pictures afterward that I noticed that I had been repeatedly drawn to what I can now see is the fulcrum of the painting: the horse’s head almost awkwardly outstretched, the red and yellow jockey pulled forward in his saddle.

In his essay on Degas, Paul Valéry points out that Degas was one of the first to study the equine photographs of Major Muybridge, which gave the painter the chance to see “the real positions of the noble animal in movement.” (Valéry, Degas Manet Morisot, Bollingen Series XLV 12, p40, translated by David Paul) Before these photographs, as Valéry says, we thought we knew what we were seeing, but, although “it seemed possible to picture the positions of a bird in flight, or a horse galloping…these interpolated pauses are imaginary.” (p41)

The way our family saw “Before the Race” is twice related to this observation of Valéry’s. At the age of two, the world is motion, wild and free, with pauses, such as the one we take before this picture. And in this little interpolated pause, I hurriedly take a few photographs that will allow me to decipher what was inside the continuous impression my eye took.

Before I saw my photographs, I knew that the painting conveyed to me a sense of excitement at once elegant and awkward, but I would not have been able to point to instances. Afterward it seemed important that the first time I photographed the horse’s head I left it in isolation, and the second time I included the beautiful patch of lavender paint to the right of the horse’s muzzle, which shows that the horse is reaching toward.

The first photograph was taken at 12:18.25,

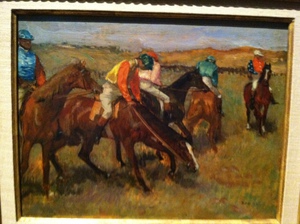

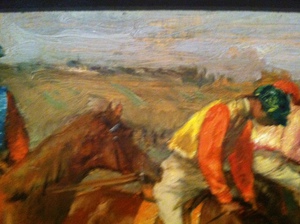

three seconds later I took this image:

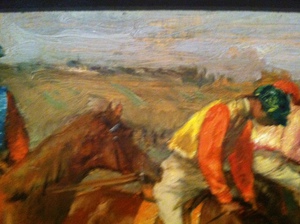

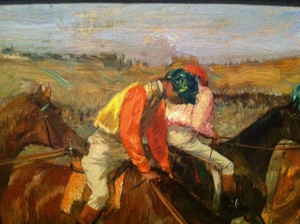

and four seconds after that:

In that seven seconds, and, more importantly, in looking at the negative space among the horses’ legs, which gave me the sense of the ground – the ground of the picture, and the fundamentals of this world – I got hold of something about the relation between the stretching horse and his universe, and when I photographed the horse's head again I framed the shot to include the clues Degas had left. Between the horse’s nose and the patch of purple is lure and distance to be overcome, something, nostrils quivering, to reach toward and something that will receive the hooves in motion.

Degas, Valéry says, “is one of the rare painters who gave due emphasis to the ground.” (p42) It is in the way a painter does the ground, he says, that one can see color “no longer as a local quality acting in isolation… but as a local result of all the different sheddings and reflections of light in space, passing and repassing between all the bodies contained in it.” The ground gives a unity, one that is “quite distinct from [the unity] of composition.” Working in this way alters the painter’s “idea of form.” (p43)

Although Valéry doesn’t put it in these words, I think you could say that when the picture is united by these “sheddings and reflections of light in space, passing and repassing between all the bodies contained in it,” then new possibilities for achieving a sense of movement are conveyed to the looker. These passings and repassings are what we feel as we follow a tripping small girl into the next gallery, and what she herself is exhilarated by as she learns to understand her own movement in space. In painting so conceived, as in the moment before the races, the potential of movement is in every trembling shadow and patch of ground. “Pushed to its limit,” Valéry concludes, “this method amounts to impressionism.” (p43)

At the Clark, “Before the Race” caught all of our attention. Little S., two, likes animals in pictures. M. and I also found ourselves momentarily absorbed in the little picture, the elegant animals, the bright-silked riders. We never know how long we have in a gallery and I hurried to document what my eye seemed to be noticing. Here are my six details, in the order taken:

It was only in looking at the pictures afterward that I noticed that I had been repeatedly drawn to what I can now see is the fulcrum of the painting: the horse’s head almost awkwardly outstretched, the red and yellow jockey pulled forward in his saddle.

In his essay on Degas, Paul Valéry points out that Degas was one of the first to study the equine photographs of Major Muybridge, which gave the painter the chance to see “the real positions of the noble animal in movement.” (Valéry, Degas Manet Morisot, Bollingen Series XLV 12, p40, translated by David Paul) Before these photographs, as Valéry says, we thought we knew what we were seeing, but, although “it seemed possible to picture the positions of a bird in flight, or a horse galloping…these interpolated pauses are imaginary.” (p41)

The way our family saw “Before the Race” is twice related to this observation of Valéry’s. At the age of two, the world is motion, wild and free, with pauses, such as the one we take before this picture. And in this little interpolated pause, I hurriedly take a few photographs that will allow me to decipher what was inside the continuous impression my eye took.

Before I saw my photographs, I knew that the painting conveyed to me a sense of excitement at once elegant and awkward, but I would not have been able to point to instances. Afterward it seemed important that the first time I photographed the horse’s head I left it in isolation, and the second time I included the beautiful patch of lavender paint to the right of the horse’s muzzle, which shows that the horse is reaching toward.

The first photograph was taken at 12:18.25,

three seconds later I took this image:

and four seconds after that:

In that seven seconds, and, more importantly, in looking at the negative space among the horses’ legs, which gave me the sense of the ground – the ground of the picture, and the fundamentals of this world – I got hold of something about the relation between the stretching horse and his universe, and when I photographed the horse's head again I framed the shot to include the clues Degas had left. Between the horse’s nose and the patch of purple is lure and distance to be overcome, something, nostrils quivering, to reach toward and something that will receive the hooves in motion.

Degas, Valéry says, “is one of the rare painters who gave due emphasis to the ground.” (p42) It is in the way a painter does the ground, he says, that one can see color “no longer as a local quality acting in isolation… but as a local result of all the different sheddings and reflections of light in space, passing and repassing between all the bodies contained in it.” The ground gives a unity, one that is “quite distinct from [the unity] of composition.” Working in this way alters the painter’s “idea of form.” (p43)

Although Valéry doesn’t put it in these words, I think you could say that when the picture is united by these “sheddings and reflections of light in space, passing and repassing between all the bodies contained in it,” then new possibilities for achieving a sense of movement are conveyed to the looker. These passings and repassings are what we feel as we follow a tripping small girl into the next gallery, and what she herself is exhilarated by as she learns to understand her own movement in space. In painting so conceived, as in the moment before the races, the potential of movement is in every trembling shadow and patch of ground. “Pushed to its limit,” Valéry concludes, “this method amounts to impressionism.” (p43)