Degas

Degas Portrait Trio

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

Three portraits by Degas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

At the MFA right now, a trio of Degas portraits are not to be missed. They can be stumbled upon in a narrow blue-green corridor on the second floor, next to the sealed off construction zone that is normally Impressionism. It is as if three of the finest musicians – one at the beginning of his career, one at the end – happened to all be passing through a town on the same night and to have the idea of playing some chamber music – and you happened to be staying at the hotel and to walk by the room they’d found for their rehearsal.

One of the portraits actually is of musicians – of a guitarist and of Degas’ father, listening.

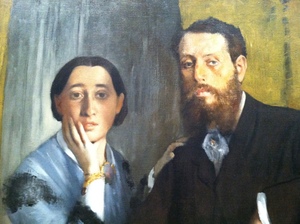

Then in the middle hangs the famous double portrait of Degas’ sister and her to my mind supercilious husband.

On the right, the formidable Duchessa di Montejasi and her two wavery daughters.

Of course they are famous pictures, but hung together in this order the experience is extraordinary.

Things noticeable: a significant progression in Degas’ style – from the middle couple painted in 1865,

to the portrait of his father and Lawrence Pagans dated 1869-72, through to the later piece in 1876.

Then there are the family relationships – the father, a little weary but firmly engaged with the music, seems almost to see his outward-gazing daughter as he looks toward the middle portrait – the mother and her two daughters on the right suggest a different balance between the generations.

The heights of the paintings, the textures, and palettes, go beautifully together. And then formal resonances: from far apart, the musician and the pair of daughters face each other, while the Duchessa and the married couple have the prominence of facing the viewer squarely, even demandingly.

And who would have thought the cramped hallway, 253, with its poor lighting and difficult bluish-green paint would make such an astonishing space for them. You have just enough room, by dint of backing and turning, to see all three at once and it is good to look from the long angles the hallway affords and to be brought into such direct confrontation with the pictures.

Degas’ beautiful-ugly palette is perfect against the wall color, which flattens out most paintings, but seems to make these only more astringent and demanding.

It is all the strictest happenstance – because the museum is renovating its main Impressionist gallery, where two of these portraits often hang, but in no clear relation to one another; because the renovation has been made the occasion of the “Boston Loves Impressionism” show; because when offered the choice of fifty great Impressionist works the public voting online chose thirty pictures and not one of these Degas portraits; because the curators, possibly a bit frustrated with the limits of curating by public taste saw an opportunity; because the cramped and difficult space is actually better for seeing these paintings then the larger halls in which they more often hang, because of all of this, a rare chance…

Do go. A little further along the hallway, you will also get to see what is possibly Cézanne’s last self-portrait, hung immediately next to his wonderful “Woman in a Red Armchair,” (moved since I last wrote about it here). This, too, is a powerful juxtaposition, strong in the tight hallway, not before displayed in like fashion. The shadow show, the Impressionism Boston does not love, is as revelatory a sequence of paintings as the seven works in the Frick’s Piero show were last year.

One of the portraits actually is of musicians – of a guitarist and of Degas’ father, listening.

Then in the middle hangs the famous double portrait of Degas’ sister and her to my mind supercilious husband.

On the right, the formidable Duchessa di Montejasi and her two wavery daughters.

Of course they are famous pictures, but hung together in this order the experience is extraordinary.

Things noticeable: a significant progression in Degas’ style – from the middle couple painted in 1865,

to the portrait of his father and Lawrence Pagans dated 1869-72, through to the later piece in 1876.

Then there are the family relationships – the father, a little weary but firmly engaged with the music, seems almost to see his outward-gazing daughter as he looks toward the middle portrait – the mother and her two daughters on the right suggest a different balance between the generations.

The heights of the paintings, the textures, and palettes, go beautifully together. And then formal resonances: from far apart, the musician and the pair of daughters face each other, while the Duchessa and the married couple have the prominence of facing the viewer squarely, even demandingly.

And who would have thought the cramped hallway, 253, with its poor lighting and difficult bluish-green paint would make such an astonishing space for them. You have just enough room, by dint of backing and turning, to see all three at once and it is good to look from the long angles the hallway affords and to be brought into such direct confrontation with the pictures.

Degas’ beautiful-ugly palette is perfect against the wall color, which flattens out most paintings, but seems to make these only more astringent and demanding.

It is all the strictest happenstance – because the museum is renovating its main Impressionist gallery, where two of these portraits often hang, but in no clear relation to one another; because the renovation has been made the occasion of the “Boston Loves Impressionism” show; because when offered the choice of fifty great Impressionist works the public voting online chose thirty pictures and not one of these Degas portraits; because the curators, possibly a bit frustrated with the limits of curating by public taste saw an opportunity; because the cramped and difficult space is actually better for seeing these paintings then the larger halls in which they more often hang, because of all of this, a rare chance…

Do go. A little further along the hallway, you will also get to see what is possibly Cézanne’s last self-portrait, hung immediately next to his wonderful “Woman in a Red Armchair,” (moved since I last wrote about it here). This, too, is a powerful juxtaposition, strong in the tight hallway, not before displayed in like fashion. The shadow show, the Impressionism Boston does not love, is as revelatory a sequence of paintings as the seven works in the Frick’s Piero show were last year.