Max Ernst

Medals

Friday, September 20, 2013

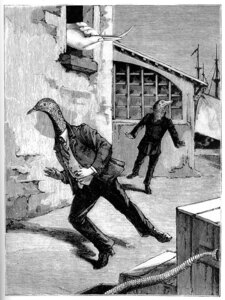

Max Ernst, Une Semaine de Bonté, plate 10, detail

Walking through the gallery, struck from the first with what felt like a wind of invention, a strong wind with particles of sand in it, it was at about the tenth image that I noticed that not only did this lion have a medal (and it was a giant medal, ridiculous, but not without pathos, because he also seemed to be a gentleman now fallen on such hard times that he might be a wandering beggar, his ailing daughter clinging to his arm, and the fact that he had retained the medal, such a large one, seemed to suggest a painful pride and attachment to some institution that had not in the end cared for him at all), not only, as I say, did this lion have a medal, but every lion had a medal.

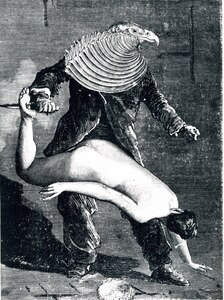

In the first “Lion de Belfort” section of Max Ernst’s Une Semaine de Bonté – the lions, the ones of authority parading through ghoulish exhibits, the night watchmen of ill intent, the one in a greatcoat seducing a dancing nude woman by playing the clarinet, the pride-engorged executioner whose victim lies down at the guillotine, the debauched reveler like an appalling caricature of a Dutch lass-on-knee genre picture – they all have medals.

Worn with obdurate aggression, the medals would be pitiful if they weren’t pernicious. The writing on the medal of the lion in plate 21 is extremely legible: “Merite Agricole, 1883” it says and hangs from a loop that seems half-clamped in the teeth of a dusty disheveled bowler-hatted better-days lion.

It was the summer of 1933; Max Ernst made these 184 collages in just a few months, while he was staying in the north of fascist Italy. All those medals – given for fifty years of military valor, colonial expeditions, police arrests, agricultural progress, upright bourgeois citizenship – all those medals for what had after all been rape, pillage, murder, surveillance, manipulation, state-sanctioned robbery and unbearable preening – all this hung heavy in the imagination and in the air over Vigoleno.

Images are photographed details from Lion de Belfort plates in catalog Max Ernst: Une Semaine de Bonté, les collages originaux, edited by Werner Spies, Paris: Gallimard, 2009.