Max Ernst

An Early Interview

Thursday, February 6, 2014

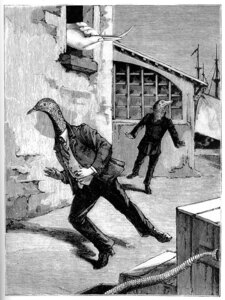

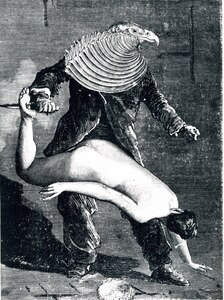

Max Ernst, Une Semaine de Bonté, 1933

In college (when I was an ardent feminist, and also somewhat uncomfortable about bodies), it seemed hard to like, or even to tolerate, the works of Max Ernst. I’m not even sure I knew which paintings were his. Now I am surprised that I seem not to have encountered even the most famous instances of his ravaging vision, like the Ange du Foyeur,

let alone the collages of Une Semaine de Bonté that have absorbed my attention in recent years.

The first time I remember suddenly seeing Ernst, what he could do as a painter, how ferocious and intelligent and clear he was, was at the Menil Museum in Houston. I had gone down there to interview Walter Hopps, one of the 20th century’s master curators, first to show Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp in California, he who brought discernment and force to the display of California artists, who worked with Kienholz and Warhol and Jay DeFeo, who had a perfect touch for Donald Judds, and did the great Oldenburg show at the Guggenheim.

We had an odd interview. I was just starting out as a writer, and had never conducted an interview before. I had been asked to write something for Modern Painters, and I don’t remember now why I came up with the idea of Hopps, perhaps it was meant to be a piece about a curator, and I had been writing about Joseph Cornell and thought that early show might be something to find out about. I remember standing in the kitchen of my parents' house, telling them that the magazine had said I could do this interview, and I remember my father saying encouragingly that this was an opportunity. My parents gave me some frequent flyer miles, and I bought a tape recorder that I was none too sure about, and flew down to Houston, and was picked up by Hopps’s very kind wife, Caroline Huber.

I had read quite a lot about Hopps and his exhibitions. I had various ways of trying to imagine his working life, could see the light in which he had worked – my parents had grown up in the southern California of the 50s and 60s where his was a radical and celebratory presence. Nevertheless, when I found myself across a table from him in his acrid office across the street from what he wryly called “the museum as office park,” designed by Renzo Piano, I realized that I had no idea what I was doing. Of course Hopps must have realized this, too, but his attitude seemed to be one of grimly marching forward. He talked of artists and artworks I knew a little something about as if he were involved in a strong colloquy with himself that I and the tape recorded merely attended. There were glimmers of dark humor in his speech, and I tried to bring these out in the piece I wrote. I couldn’t then articulate what subsequent events made me realize, namely, that he was already ill and facing down the question of what what he had done had meant.

I felt the edge of it. His wife anxiously told him not to smoke during the interview and I had wondered about that and then been surprised when he immediately lit up and smoked – smoked not like a chimney, more like a furnace, like he was eating the cigarettes – while on the desk in front of him he set going an odd little gnashing machine that I think was a sort of ashtray but was also in a way meant to consume the smoke, to draw it down and keep it from filling the room. My remaining impression is of the jaws of this machine clanking away at their ineffectual labor while the room became thick, hazy, a pall of smoke. I believe I was enjoined not to tell his kind and worried wife, though of course she would immediately smell what had happened when he was picked up afterwards.

Perhaps not so many still came to talk to him about paintings. He could have used a more knowledgeable and forceful interlocutor, but perhaps it was still a welcome occasion to get out to the office – he was now an emeritus curator – and to speak of these things.

When he had done, I shook myself from the smoky listening stupor and he said we would walk through some of the rooms he had done. There were the Judds, clean-tempered force fields that Hopps had installed with autistic clarity and there, to my surprise, lining the walls of a small room, were what I remember as four Max Ernsts that I surprisingly loved.

Hopps believed in hanging paintings to be ready for a fist-fight with the viewer, much lower than the height dictated by blockbuster shows where crowds need to see over one another’s shoulders. He believed the viewer and the painting should be body to body and sometimes quoted another Menil curator, Jermayne McAgy saying that they should “hit the tits.” This seemed to be just the kind of context Ernst needed because the paintings were suddenly so alive, so arresting in their life that I was shaken and drawn and a little disoriented. It was at least another five years before I had a similar experience of La Semaine de Bonté and I didn’t look at Ernst in the meantime, but you don’t forget raw force like that, and from then I knew it was there.

Walter Hopps died not long after my small article was published. I know that he and his wife had liked the draft I checked with them; that was the end of our contact. I thought I should try to reach her and to see if she would like the tapes of his muffled clenched voice with the grinding cigarette machine drawing him out. I had the instinct that it would be right to send them, and at the same time could not quite feel that any record really existed, or was mine to send. I felt that I had watched him as he barricaded himself behind something, and had emerged from the room as if from a dream.

This all came back to me on Tuesday, out walking in the snow, S. asleep in the stroller. We had returned to Cambridge after being home at my mother’s, S. and I. Sunday was the anniversary of my father’s death. He did not smoke, but he died of cancer in his lungs, and toward the end I sat by him, amid the oxygen machines. He talked, and I listened with a sharp, painful attention.

For years I have been trying to write about Max Ernst, and this year I have had a puzzling feeling that there would be something to say about Ernst’s work and my father’s death together.

Something – etched and strange – in this configuration. A man who can feel in his lungs that the end is coming; two hopeless, helpful machines – the little cigarette jaws, the little tape-recorder – trying desperately to fight back to life, to hang on to its meaning; a young incomprehending woman sitting by, catching at the edges of this parade of figures for whom life has been violent and radiant. And then: a momentary experience of razor-sharp clarity about deeply mysterious objects that have the hybridity and continuity of dreams. This followed by fumbling efforts to ascertain in language what might have been there. None of this is foreign to the capacious and impossible work of Max Ernst.