Gorky

Surrealism and Form

Sunday, November 3, 2013

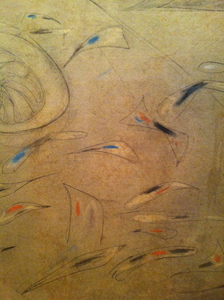

Arshile Gorky, Summation, 1947, iphone detail

There are other feelings for form, of course, but that doesn’t mean the Surrealists didn’t have formal feelings. Form is often described in spatial terms, as arrangements of objects, as landscapes with prominent and receding features. Perhaps the Surrealist feeling for form could be evoked by inversion: one could speak of a disarray of objects, or of interior landscapes in which prominence is, like that in dreams, more a matter of excitation and disturbance.

This is not to say that when you look at, say, a Max Ernst collage, your eye is not still balancing the long pointed beak of the rooster against the long line of the legs of the naked woman he has turned over his knee, but that your awareness of the beak and the body, as a beak and a body, are affecting your seeing as loci of attention in a way that is not mostly about parallel lines but about balancing visceral experiences and grappling with perceived and imagined relations between them.

The thought I’ve been trying to get articulated for a few days, since seeing Arshile Gorky’s Summation, is that these turbid experiences of suggested meaning might still in some way be understood as formal.

I rushed into the MoMA last Saturday at 5:00 (the museums closes at 5:30). I didn’t plan to go, had been in New York for five days without setting foot in a museum, had given up on the possibility of going, all of us, the baby, too, were sick, we were leaving early the next morning. After a meeting, I had been unable to get a cab for fifteen blocks and realized I was within blocks, decided to chance it…

These are all aspects of seeing art in New York, but I’m not sure which should be brought out and which let drop. I was hoping to hit Abstract Expressionism. My father loved Rothko and I thought maybe if I got one of those I could use my ten minutes for missing him, but the one I saw through a doorway opening had a kind of bright lime green edge that I recoiled from and before I quite realized what was happening I saw a Gorky and thought I’ve been meaning to think about Gorky and stopped.

In the wall text next to Summation, Gorky is quoted as saying, “There is my world.” I could see from the dates that he had died the next year, and remembered dimly that there was something untimely and terrible about his death. [I looked it up later. He killed himself the following year, at the age of forty-four, after a gruesome two years, in which his studio burned down, a car accident left him with a broken neck and a temporarily paralyzed painting arm, and his wife left him, and took their two children.] What had stayed in my mind was the sense that he had been an extremely important link from the Surrealists to the Abstract Expressionists – and that his loss had been bitterly mourned by both André Breton and Willem De Kooning.

The significance of Gorky’s influence was pointed out both in the Whitney drawing retrospective (winter 2003-2004), a show I thought was very profound, and in “Abstract Expressionist New York,” at the MoMA three years ago. Although people do talk about it, I still think it is easy to overlook how totemic and dream-oriented the Abstract Expressionists were in their early days. Frank O’Hara’s great essay on Jackson Pollock has a long useful section on Surrealism.

Another approach in the direction of my hoped-for thought might be: if one thinks of the forms discovered by the Surrealists as being in some way taken in and then diffused throughout the canvases of the Abstract Expressionists then one could in a way actually be a witness to this in looking at the works of Gorky.