Delacroix

Delacroix's Palette

Saturday, June 28, 2014

The Palette of Delacroix, from the Musée Delacroix

The studio was recommended to Delacroix by the restorer and color merchant Etienne Haro, who knew that the artist, unwell in his later years, needed to be within walking distance of St.-Sulpice, where he had undertaken a last sequence of great murals.

When he was young, Delacroix once said to his friend Charles Baudelaire, he could only work if he knew he had somewhere to be that evening, a ball, music, but as he grew older, the discipline of work grew in him and he worked indefatigably. He had visitors, but not so very many, and he kept his last illness private. Even a good friend like Baudelaire was shocked by the news of his death and wrote sorrowfully of how they would no longer find him in that grand square space "where reigned, in spite of our rigid climate, an equatorial temperature."1

A study in hot and cold, Delacroix as a personality and an artist was in continual motion between shade and gleam. He was revered for his color sense, both daring and precise, and the palettes now on display at the Musée Delacroix make his color sense dramatically visible.

Here you can see, unusually, not a rainbow or color wheel, but hot colors intermingled with cold ones, and dark contrasts grouped together with corresponding brights. The artist mixed his shades in advance and kept careful notes of each one’s composition. In Les Palettes de Delacroix (1930), Léon Piot noted that when Delacroix was ill, he would have his palette brought to his bed and spend the day there mixing colors. Baudelaire wrote, “I have never seen a palette as minutely and delicately prepared as that of Delacroix. It resembled a bouquet of flowers, knowingly arranged.”2 On its website, the Musée Delacroix points out that as time went on the artist, “fragmented more and more the tones, focusing less and less on real color as opposed to shadows, halftones, and reflections.”

Baudelaire evidently felt sympathetic to, and recognized by, the atmosphere created by Delacroix’s color. “It seems that such color thinks for itself, independently of the object it clothes,” Baudelaire is said to have said, “The effect of the whole is almost musical.”3

This palette

was said to have been given by Delacroix to Henri Fatin-Latour, a great admirer of Delacroix. Fatin-Latour, angered by the lack of official commemoration of the master’s death, painted an Hommage à Delacroix.

The group portrait includes Fatin-Latour himself (in white blouse), James McNeill Whistler (standing center,) Edouard Manet (standing immediately to the right of the portrait of Delacroix) and Baudelaire (seated right corner.)

Six years later, Fatin-Latour painted a similar group portrait, called A Studio at Batignolles that, with its depictions of Manet, Renoir, Zola, Bazille, and Monet, stands as both manifesto for and document of the Impressionist movement in something like the manner of John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence:

The palette that may have belonged to both Delacroix and Fatin-Latour was eventually donated to the Musée Delacroix by the granddaughter of Léon Riesener, and the Riesener family, through its friendship with the Morisot sisters, provided another, personal, conduit by which the palette of Delacroix was transmitted to the Impressionists.

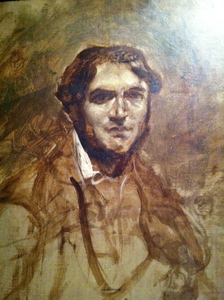

This summer, the Musée Delacroix has an exhibition of works that show the influence of Shakespeare on Delacroix. Like Berlioz, Delacroix was greatly moved by the force of drama in the works of Shakespeare and there are wonderful etchings of instants of great intensity from Hamlet (Hamlet on the terrace approached by his father’s ghost, the moment before the stabbing of Polonius, the moment “up, sword” of deciding not to kill Claudius at prayer). There is also an oil sketch of Léon Riesener, a cousin and confidante of the painter, himself a painter, and a legatee of Delacroix’s.

This portrait shows a broad and sympathetic face, tones all of brown and white. In the background and upside down are discernible sketches for another picture, Hamlet and Horatio in the cemetery with the skull of Yorick.

Bequeathal, and legacy were vexed issues for Delacroix, who, says Baudelaire, was increasingly preoccupied with which of his contributions would endure.

Walter Benjamin notes the aptness of Léon Daudet’s phrase for Baudelaire. Daudet writes that Baudelaire had a “trap-door disposition, which is also that of Prince Hamlet.”4 I take this to mean a theatrical, or a magician’s, feeling for circumstances and their manipulation. Appearances and disappearances, sudden dispersals, going within to get out. There seems to be something of Delacroix in the phrase, too.

Another inheritor of Delacroix was Berthe Morisot, who, in an early summer of her training as a painter was working side-by-side with her sister in the town of Beuzeval in Normandy. Their father had rented for them a mill belonging to Léon Riesener, and the Morisot sisters were soon close to, and much encouraged by, the whole Riesener family. In her notebook, Berthe Morisot recorded an anecdote they related: “Delacroix composed his palette with such precision that he could have it prepared each morning by Jenny, his maid, while he was painting his Apollo ceiling or rather while he had Andrieux paint it as he remained below. One day, he called out to him to use a No. 2 pink and Andrieux thought he would catch him out with a No. 3. ‘No, no, exclaimed Delacroix, I said a No.2.’ That is absolutely the sensation of a musician.”5

I see two ways out of this series of reflections: one is to try to see further inside the man, the other to try to see further into the legacy of his works. These efforts do not amount to the same thing, but perhaps could be displayed immediately next to each other.

Walter Benjamin, whose interest in Delacroix grew in part from Benjamin’s profound relationship to the works of Baudelaire, notes that Delacroix was interested in photography, and that his paintings “escape the competition with photography, not only because of the impact of their colors, but also (in those days there was no instant photography) because of the stormy agitation of their subject matter. And so a benevolent interest in photography was possible for him.”6 The ever more profound and fragmentary sense of color, and the idea of creating motion through the juxtaposition of contrasting colors, these went on being a significant part of how painting responded to photography through the rest of the 19th century.

Baudelaire said that his friend Delacroix was a peculiar combination of the “sauvage,” and the “homme du monde.” He was, writes the poet, “passionately enamored of passion, and coldly determined to seek out the means of expressing passion in the most visible manner.”7 In his austere seclusion he would, Baudelaire wrote, find the colors in which to bathe his scenes so that they had their own life. “As a dream is placed in the colored atmosphere proper to it, so a conception, become a composition, must moves in a colored milieu particular to it.”8

1 Baudelaire, Critque d’art, “Eugene Delacroix, son oeuvre et sa vie,” p421, translations mine.

2 Baudelaire, Critique d’art, p408

3 from Ernest Seillière, Baudelaire, (Paris, 1931) cited in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, edited Tiedemann, translated Eiland and McLaughlin, (Cambridge, 1999) p277.

4 Daudet, Les Pélerins d’Emmaus, Paris, 1928, p101, cited in Benjamin, Arcades Project, p265.

5 Morisot, Notebook, 1885, 1887-8, p12-13, cited in Marianne Delafond and Caroline Genet-Bondeville, Berthe Morisot or Reasoned Audacity, Paris, 2011, p16

6 Benjamin, Arcades Project, p678.

7 Baudelaire, Critique d’art, p418, p406.

8 Baudelaire, p408.