Giacometti

Giacometti and James Lord

Monday, April 2, 2018

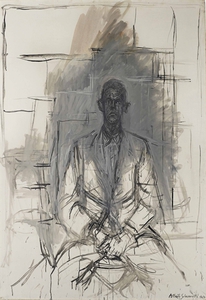

Alberto Giacometti, drawing, Portrait de James Lord, 1954

Preparing for class this week, I reread James Lord’s book Giacometti: A Portrait. The book is broken into the eighteen sittings Lord did with Giacometti one fall, in September and October of 1964, for a painted portrait. Lord’s book was published the following year.

The class has just begun, but the students and I intend to reflect on drawing, and especially on returning to the same work repeatedly, and I assigned the book in part because of its repetitiveness. It’s as if Giacometti is practicing painting Lord’s portrait – as he goes on, perhaps most of the times he does it, he does it a little better, but then in despair he paints out large parts of it, in gray, white. He begins again, with some layers remaining of previous efforts, to define the head with strong thin blacks. When it is succeeding, there is a sense of space, of the head and what is around the head; at other times it seems lopsided, opaque. He could go on this way a long time. Neither Giacometti nor Lord has any thought that the painting would eventually be finished, the question is at what point to abandon it.

I don’t know if it would be right to say that I have spent a fair amount of time looking at Giacometti, or if it would be more accurate to say that the time I have spent has felt very acute, indelible. I can return to the experiences with clarity, re-enter them. The works let me strain alongside them, strain to an utmost, and that is memorable. Intermittently, they also give me a sense of rest. The sense that they are unfinished because their maker fought as hard as possible creates around them a special atmosphere – quiet, rigor, charity – that resists even something of the stealth of museumization. The work lets me feel not just that I am forgetting the price it fetched at some auction in a world I have no access to, or the women with expensive educations and scarves writing smooth copy to be posted nearby (I might be such a woman, I sometimes am,) or the gift shop hovering in the background that sells the scarves – lets me not forget these things, but somehow go on thinking without being debased, lets me think instead, here is something, I am thinking about it.

Lord talks about a similar kind of alternation between strain and rest – rest is the sense of having contributed – in the experiences of posing for Giacometti. Because Lord is a little bit sneaky, a little bit facile, he also brings this to the tale. Lord is always plotting how to steal a little bit of the experience – he is taking photographs of every stage of the work, he is slipping out to make notes about it and then lying to Giacometti about what he is doing, when Giacometti throws out and destroys some drawings, Lord fishes a few out of the trash, on the final day, he is secretly trying to get Giacometti to stop the cycle of painting on an upswing, toward clarity, which will make the portrait, which Giacometti has told him he will give him, more beautiful to Lord, and more valuable. Giacometti must have known all this. He apparently used to say that he wasn’t interested in portraying the inner life, it was hard enough just to get the outward aspect, but people, including Lord, thought he was a good judge of character. I think it was a relief to Lord, and perhaps this allows me to recognize part of the relief I feel myself in the vicinity of the works, that Giacometti was not concerned about thieves.

The class has just begun, but the students and I intend to reflect on drawing, and especially on returning to the same work repeatedly, and I assigned the book in part because of its repetitiveness. It’s as if Giacometti is practicing painting Lord’s portrait – as he goes on, perhaps most of the times he does it, he does it a little better, but then in despair he paints out large parts of it, in gray, white. He begins again, with some layers remaining of previous efforts, to define the head with strong thin blacks. When it is succeeding, there is a sense of space, of the head and what is around the head; at other times it seems lopsided, opaque. He could go on this way a long time. Neither Giacometti nor Lord has any thought that the painting would eventually be finished, the question is at what point to abandon it.

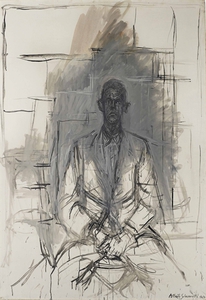

[The portrait as it was abandoned in October of 1964 and subsequently sold.]

I don’t know if it would be right to say that I have spent a fair amount of time looking at Giacometti, or if it would be more accurate to say that the time I have spent has felt very acute, indelible. I can return to the experiences with clarity, re-enter them. The works let me strain alongside them, strain to an utmost, and that is memorable. Intermittently, they also give me a sense of rest. The sense that they are unfinished because their maker fought as hard as possible creates around them a special atmosphere – quiet, rigor, charity – that resists even something of the stealth of museumization. The work lets me feel not just that I am forgetting the price it fetched at some auction in a world I have no access to, or the women with expensive educations and scarves writing smooth copy to be posted nearby (I might be such a woman, I sometimes am,) or the gift shop hovering in the background that sells the scarves – lets me not forget these things, but somehow go on thinking without being debased, lets me think instead, here is something, I am thinking about it.

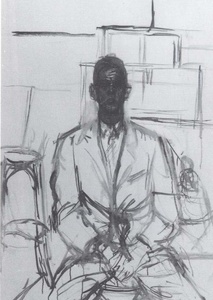

[A detail of Lord’s painted face as posted by someone on the internet.]

Lord talks about a similar kind of alternation between strain and rest – rest is the sense of having contributed – in the experiences of posing for Giacometti. Because Lord is a little bit sneaky, a little bit facile, he also brings this to the tale. Lord is always plotting how to steal a little bit of the experience – he is taking photographs of every stage of the work, he is slipping out to make notes about it and then lying to Giacometti about what he is doing, when Giacometti throws out and destroys some drawings, Lord fishes a few out of the trash, on the final day, he is secretly trying to get Giacometti to stop the cycle of painting on an upswing, toward clarity, which will make the portrait, which Giacometti has told him he will give him, more beautiful to Lord, and more valuable. Giacometti must have known all this. He apparently used to say that he wasn’t interested in portraying the inner life, it was hard enough just to get the outward aspect, but people, including Lord, thought he was a good judge of character. I think it was a relief to Lord, and perhaps this allows me to recognize part of the relief I feel myself in the vicinity of the works, that Giacometti was not concerned about thieves.

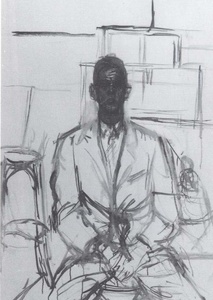

[A version of the portrait in progress as James Lord photographed it.]