Delaney

Abstraction and Eyes

Sunday, April 13, 2014

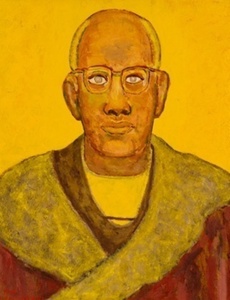

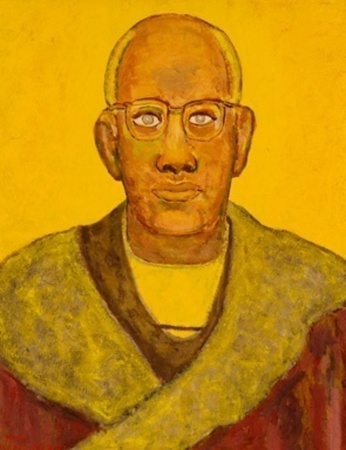

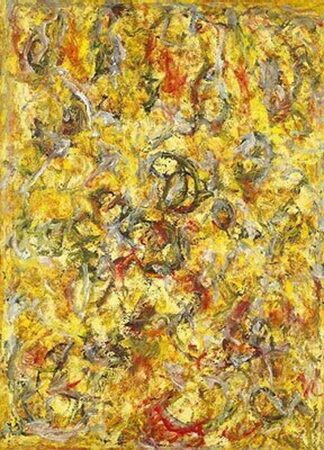

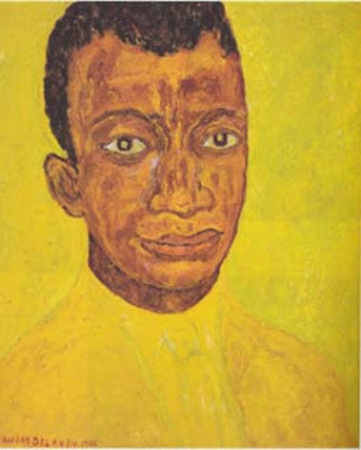

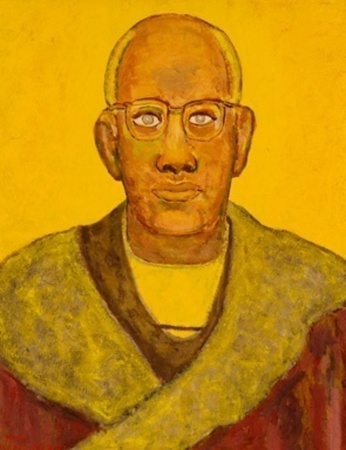

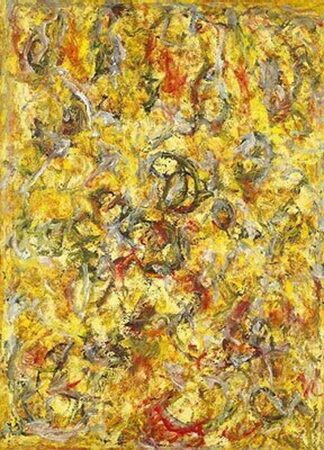

One of the unusual aspects of Beauford Delaney’s work as an abstract painter was that even late in his career, when he lived in Paris and had moved very fully into abstraction, he also painted very specific and characterful portraits. These two kinds of paintings were shown together during his lifetime – at, for example, the Galerie Lambert on the Île St. Louis in 1964 – and have been shown so since his death – in particular at the Levis Gallery in Chelsea last year, an exhibition, that, regrettably, I was not in New York to see. [Here are Dr. Ahmed Bioud, 1968, and an untitled work from ca. 1958-9.]

From accounts I’ve read, this alternating display of persons and abstractions asks something very particular of the viewer. I caught a suggestion of the experience from watching a video of the opening at the Levis Gallery – it might interest the reader to look at it here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0ZJcvenRpw

One thing that clearly holds the two approaches together is something essential about the paint itself, its handling. Responding to the 1964 show, the French art critic Jean Guichard-Meili felt that, in the end, the two kinds of works “do not differ… Background, clothing, hands, faces, are the pretext for autonomous harmonies.” Guichard-Meili describes the paint itself as having “movements of internal convection,” and says that the one experiences “the vibrations of underlying design.” [This account appeared in the journal Arts and is quoted in David Leeming’s wonderfully gentle biography of Delaney, Amazing Grace, p165.]

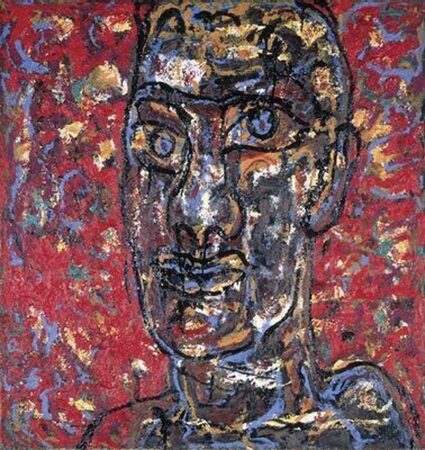

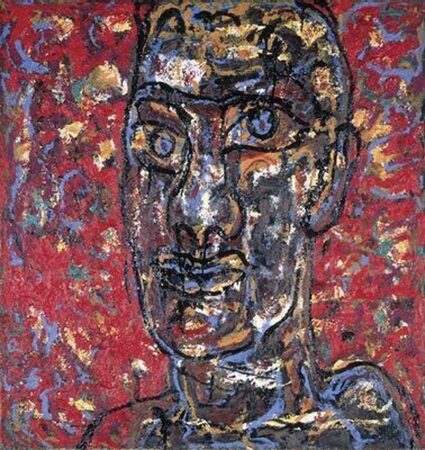

A similar idea – that the patterning and movement of the paint is common to both the portraits and the abstractions – is to be found in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts catalog of its Delaney retrospective of 2004-2005. Here is Delaney’s The Sage Black (James Baldwin) of 1967. [Photo courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.]

The catalog says that, “Delaney superimposed a calligraphic outline on the abstract composition of reds, greens, yellows and blues. Filled with all the colors of a flame, this incendiary, combustible background peers through Baldwin’s form…” This language seems to me to greatly simplify what I can tell even from reproductions of the work, which is that the colors shift dramatically between the ground and the figure, that the background does not merely “peer through,” but is transformed, condensed, reconstituted in and by the person. I find it hard to understand the eyes in this painting.

* * *

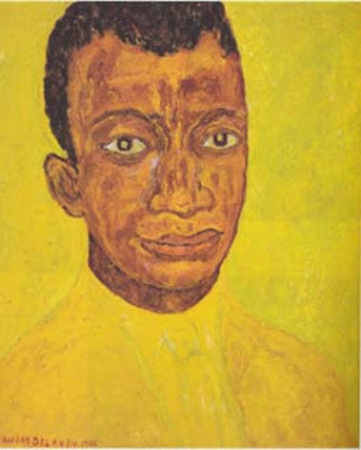

In Paris, Monique Y. Wells maintains a wonderful website called Les Amis du Beauford Delaney, an important resource, and she has two entries on Delaney’s portraits of his friend James Baldwin. This was one of the most significant friendships of either man’s life. On the site, the art historian Catherine St. John offered comments on another portrait of Baldwin, this one backed in Delaney’s signature yellow.

St. John writes two things that seem to me exactly to the point. The first is her description of how to consider Delaney’s yellow: “His tactile surfaces of brilliant colors are prime carriers of light and space and it is in his use of yellow - ochre, cadmium, lemon - that we discover the substance of light in relation to spirit.” She goes on to suggest a way of thinking about this relationship, of light to spirit, in terms of the figure. “The isolated, self-contained image of Baldwin is the special intersection of the world of light and the subjective consciousness that Beauford Delaney brought to his portraits. It is a supremely expressive portrait in which the eyes, the most intimate and powerful feature of the face, act like magnets.”

This is a deeper understanding of the relation between abstraction and the figure in Delaney’s work and near to something Delaney himself said in trying to explain the single project that lay behind what seemed two divergent methods. David Leeming says that “Beauford explained to friends that both approaches were studies in light revealed—the light that gave meaning to the individuals depicted in the large volumes of color in the portraits and the light considered directly as contained in the juxtaposition of minute and closely packed bits of blue, red, and especially yellow in the abstract paintings.” [Leeming, p164.]

There is much to be said, and much has been said, on the metaphysics of inward light in Delaney (and in Baldwin) but here I want to confine myself to one observation, which is that the eyes, in some important way, do not have it. They seem in their dark opacity, or even in their dark brilliance, to reflect on light rather than to be lit. Like magnets, they also have darkness, and draw us by an absorbing force that pulls inward. And this seems very precisely understood. For the eyes would have to be the very site of inversion, the very place where the abstract meets the formed person, the lens across which the inner and outer worlds interpret one another.

From accounts I’ve read, this alternating display of persons and abstractions asks something very particular of the viewer. I caught a suggestion of the experience from watching a video of the opening at the Levis Gallery – it might interest the reader to look at it here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0ZJcvenRpw

One thing that clearly holds the two approaches together is something essential about the paint itself, its handling. Responding to the 1964 show, the French art critic Jean Guichard-Meili felt that, in the end, the two kinds of works “do not differ… Background, clothing, hands, faces, are the pretext for autonomous harmonies.” Guichard-Meili describes the paint itself as having “movements of internal convection,” and says that the one experiences “the vibrations of underlying design.” [This account appeared in the journal Arts and is quoted in David Leeming’s wonderfully gentle biography of Delaney, Amazing Grace, p165.]

A similar idea – that the patterning and movement of the paint is common to both the portraits and the abstractions – is to be found in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts catalog of its Delaney retrospective of 2004-2005. Here is Delaney’s The Sage Black (James Baldwin) of 1967. [Photo courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.]

The catalog says that, “Delaney superimposed a calligraphic outline on the abstract composition of reds, greens, yellows and blues. Filled with all the colors of a flame, this incendiary, combustible background peers through Baldwin’s form…” This language seems to me to greatly simplify what I can tell even from reproductions of the work, which is that the colors shift dramatically between the ground and the figure, that the background does not merely “peer through,” but is transformed, condensed, reconstituted in and by the person. I find it hard to understand the eyes in this painting.

* * *

In Paris, Monique Y. Wells maintains a wonderful website called Les Amis du Beauford Delaney, an important resource, and she has two entries on Delaney’s portraits of his friend James Baldwin. This was one of the most significant friendships of either man’s life. On the site, the art historian Catherine St. John offered comments on another portrait of Baldwin, this one backed in Delaney’s signature yellow.

St. John writes two things that seem to me exactly to the point. The first is her description of how to consider Delaney’s yellow: “His tactile surfaces of brilliant colors are prime carriers of light and space and it is in his use of yellow - ochre, cadmium, lemon - that we discover the substance of light in relation to spirit.” She goes on to suggest a way of thinking about this relationship, of light to spirit, in terms of the figure. “The isolated, self-contained image of Baldwin is the special intersection of the world of light and the subjective consciousness that Beauford Delaney brought to his portraits. It is a supremely expressive portrait in which the eyes, the most intimate and powerful feature of the face, act like magnets.”

This is a deeper understanding of the relation between abstraction and the figure in Delaney’s work and near to something Delaney himself said in trying to explain the single project that lay behind what seemed two divergent methods. David Leeming says that “Beauford explained to friends that both approaches were studies in light revealed—the light that gave meaning to the individuals depicted in the large volumes of color in the portraits and the light considered directly as contained in the juxtaposition of minute and closely packed bits of blue, red, and especially yellow in the abstract paintings.” [Leeming, p164.]

There is much to be said, and much has been said, on the metaphysics of inward light in Delaney (and in Baldwin) but here I want to confine myself to one observation, which is that the eyes, in some important way, do not have it. They seem in their dark opacity, or even in their dark brilliance, to reflect on light rather than to be lit. Like magnets, they also have darkness, and draw us by an absorbing force that pulls inward. And this seems very precisely understood. For the eyes would have to be the very site of inversion, the very place where the abstract meets the formed person, the lens across which the inner and outer worlds interpret one another.