Beauford Delaney Eyes

Friday, June 5, 2020

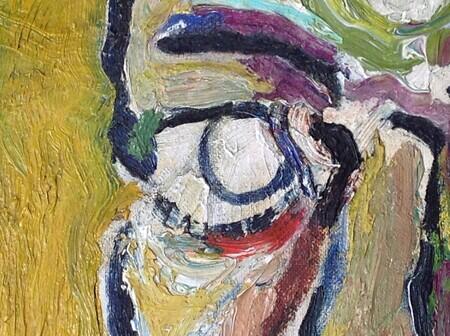

Beauford Delaney, Self-Portrait, 1944, Art Institute of Chicago. Detail photo Rachel Cohen.

Drawing together the two paintings I’ve been considering this week – Delaney’s Untitled (Village Street), 1948, and his Self-Portrait, 1944.

Beauford Delaney, Untitled (Village Street), 1948, Terra Foundation of Art. All detail photos Rachel Cohen.

When I was with Untitled (Village Street), I noticed the repeating circles and ovals – lights, clouds, signs, puddles.

I thought of the story that James Baldwin tells over and over, and that writers about Baldwin and Delaney tell over and over:

I remember standing on a street corner with the black painter Beauford Delaney down in the Village, waiting for the light to change, and he pointed down and said, “Look.” I looked and all I saw was water. And he said, “Look again,” which I did, and I saw oil on the water and the city reflected in the puddle. It was a great revelation to me. I can’t explain it. He taught me how to see, and how to trust what I saw. Painters have often taught writers how to see. And once you’ve had that experience, you see differently.

— James Baldwin, Interview in the Paris Review with Jordan Elgrably, Spring 1984

Waiting for the light to change. Little moment of suspension in movement through modern city, and also spiritual state. City iridescence within the dirtiness and pollution, using the sight you have.

When I went back around to the other side of the barrier in the storage space to look again at Self-Portrait, 1944, I saw the eyes differently.

For the talk I gave at the conference James Baldwin and Beauford Delaney: In a Speculative Light, I put two detail photographs together, an eye and a puddle:

**

I want to make mention of Delaney’s mental illness. He heard voices. He had episodes of feeling acutely that he was pursued, and that the voices were calling him the kinds of things people did, and do, hatefully call a person who is Black and queer and poor and vulnerable. At the end of his life, he lived in an institution. I do not want to make his mental illness explanatory of the visionary quality of his painting. I want, rather, to give you a sense of the firmness and comprehensiveness of his understanding. What paint can show. It is neither the cloud, nor the eye, alone, it is the two reflecting one another.