Renoir

Reading Toward Renoir

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Monet Painting in his Garden at Argenteuil, 1873, Wadsworth Atheneum

Renoir to me has always been the outlier – the one among the Impressionists without austerity enough to make room for me. Too sweet, too voluptuous. All skin, no air. But loved by Leo Stein, Gertrude’s brother, who understood Cézanne’s apples right away. When he and Gertrude split up the household they had for decades shared, both wanted the apples, but were content for her to keep the Picassos, him to take the Renoirs.

---

Stein was a man for whom sensuality was difficult and I’ve wondered if Renoir seemed to offer in an uncomplicated way, enjoyment. It sounds from the memoir written by the son, Jean Renoir, as if the painter was a rare person, fundamentally tolerant of himself and of other people. It’s true that his paintings show people taking pleasure in life. Who else does that? Perhaps some Dutch painters, though there is often a suspicion that Frans Hals is laughing at his revelers. In Renoir they take a quiet pleasure. Jean Renoir says the sitters have “serenity.” They are settled, but they are still full of the activity of being themselves; they look out on their surroundings and see much to interest them.

---

When the son spoke to the father of different women he had admired and painted, a great variety of women, society ladies and street walkers, the painter was full of appreciation, his greatest commendation, “she posed like an angel.” In the portraits, the sitter and the painter seem to share a lively and devoted understanding.

---

There is a Renoir of Monet in a garden painting. I wondered when I saw the reproduction recently if it were a Renoir or a Monet. The flowers have a lot of whites reaching upward in a way that I thought might be Monet, but when I checked the back flap I was not really surprised to see that it was a Renoir. The way to tell would have been to look at the figure, the painter in his hat, all his energy turned toward his craft. Features, soft, almost indistinct, but the impression of the face is of concentration and happiness. He could be humming.

---

Apparently Renoir loved all craftsmanship. He had himself begun by painting porcelain and then window shades. His father was a very good tailor. Renoir used to lament the passing of know-how and the replacement of hand industries by machines. He had felt grateful to grow up in the old Tuileries neighborhood before it was torn down – all the stairways and niches and small corner carvings of the buildings bespoke the loving care of craftspeople. Women, he told his son, at their daily tasks, know how to live. “Around them I feel happy.”

---

In a state of happy engagement people are very close to the surface, much closer then we usually are able to be even with close friends, whose faces barricade them in reserve. Perhaps what I have taken for too much luster, too much skin, is really more unsettling, the close presence of people in a state to which we are no longer accustomed, as we may find the unsanitized smells from earlier eras – a barnyard, a field of clover, dried lavender in sheets – overwhelmingly, almost intolerably, sweet.

Reading Toward Renoir II

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

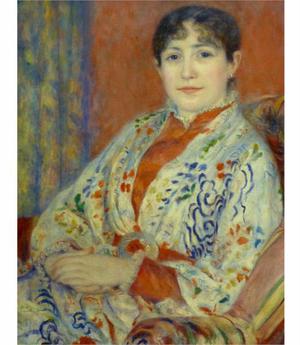

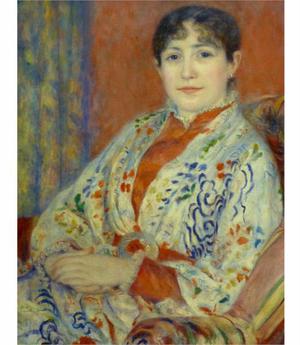

Renoir, Madame Hériot, 1882

I find that in reading Jean Renoir’s Renoir, my father, I am thinking of Maxim Gorki’s memoir of Chekhov, a most beautiful reminiscence. In particular of a story I have always loved, and which has to be quoted complete with Gorki’s introductory meditation. It is as follows:

I think that in Anton Chekhov’s presence everyone involuntarily felt in himself a desire to be simpler, more truthful, more one’s self; I often saw how people cast off the motley finery of bookish phrases, smart words, and all the other cheap tricks with which a Russian, wishing to figure as a European, adorns himself, like a savage with shell’s and fish’s teeth. Anton Chekhov disliked fish’s teeth and cock’s feathers; anything” brilliant” or foreign, assumed by a man to make himself look bigger, disturbed him; I noticed that whenever he saw any one dressed up in this way, he had a desire to free him from all that oppressive, useless tinsel and to find underneath the genuine face and living soul of the person. All his life Chekhov lived on his own soul; he was always himself, inwardly free, and he never troubled about what some people expected and others – coarser people – demanded of Anton Chekhov. He did not like conversations about deep questions, conversations with which our dear Russians so assiduously comfort themselves, forgetting that it is ridiculous, and not at all amusing, to argue about velvet costumes in the future when in the present one has not even a decent pair of trousers.

Beautifully simple himself, he loved everything simple, genuine, sincere, and he had a peculiar way of making other people simple.

Once, I remember, three luxuriously dressed ladies came to see him; they filled his room with the rustle of silk skirts and the smell of strong sent; they sat down politely opposite their host, pretended they were interested in politics, and began “putting questions”: “Anton Pavlovich, what do you think? How will war end?”

Anton Pavlovic coughed, thought for a while, and then gently, in a serious and kindly voice, replied: “Probably in peace.”

“Well, yes… certainly. But who will win? The Greeks or the Turks?”

“It seems to me that those will win who are the stronger.”

“And who, do you think, are the stronger?” the ladies asked together.

“Those who are the better fed and the better educated.”

“Ah, how clever,” one of them exclaimed.

“And whom do you like best?” another asked.

Anton Pavlovich looked at her kindly, and answered with a meek smile: “I love candied fruits… don’t you?”

“Very much,” the lady exclaimed gaily.

“Especially Abrikossov’s,” the second agreed solidly. And the third, half closing her eyes, added with relish: “It smells so good.”

And all three began to talk with vivacity, revealing, on the subject of candied fruit, great erudition and subtle knowledge. It was obvious that they were happy at not having to strain their minds and pretend to be seriously interested in Turks and Greeks, to whom up to that moment they had not given a thought.

When they left, they merrily promised Anton Pavlovich: “We will send you some candied fruit.”

“You managed that nicely, “ I observed when they had gone.

Anton Pavlovich laughed quietly and said: “Everyone should speak his own language.”

[Maxim Gorky, Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Andreyev. With an introduction by Mark Van Doren. Translator not given. New York: Viking Press, 1959, pp74-76.

Although the translator’s name is, astonishingly, nowhere given in the volume, I assume the translation is a good one and that the tiny hint of condescension in “not having to strain their minds,” is Gorki’s, though perhaps, under the influence of Chekhov, the younger writer felt no such thing and it is at the further remove of translation that the note has entered the composition. I am certain, though, and in part from reading this passage of Gorki’s, that the feeling is not Chekhov’s, as it seems it would not be Renoir’s. Chekhov’s idea of a person may be more complicated than Renoir’s – it does seem that the regrets and struggles of his figures have more bitterness in them – but, as in Renoirs, there is the sense in the stories that it is natural for people to be themselves, and that the task of the painter or the writer is to help them to circumstances in which they are.