Renoir

Reading Toward Renoir

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Monet Painting in his Garden at Argenteuil, 1873, Wadsworth Atheneum

Renoir to me has always been the outlier – the one among the Impressionists without austerity enough to make room for me. Too sweet, too voluptuous. All skin, no air. But loved by Leo Stein, Gertrude’s brother, who understood Cézanne’s apples right away. When he and Gertrude split up the household they had for decades shared, both wanted the apples, but were content for her to keep the Picassos, him to take the Renoirs.

---

Stein was a man for whom sensuality was difficult and I’ve wondered if Renoir seemed to offer in an uncomplicated way, enjoyment. It sounds from the memoir written by the son, Jean Renoir, as if the painter was a rare person, fundamentally tolerant of himself and of other people. It’s true that his paintings show people taking pleasure in life. Who else does that? Perhaps some Dutch painters, though there is often a suspicion that Frans Hals is laughing at his revelers. In Renoir they take a quiet pleasure. Jean Renoir says the sitters have “serenity.” They are settled, but they are still full of the activity of being themselves; they look out on their surroundings and see much to interest them.

---

When the son spoke to the father of different women he had admired and painted, a great variety of women, society ladies and street walkers, the painter was full of appreciation, his greatest commendation, “she posed like an angel.” In the portraits, the sitter and the painter seem to share a lively and devoted understanding.

---

There is a Renoir of Monet in a garden painting. I wondered when I saw the reproduction recently if it were a Renoir or a Monet. The flowers have a lot of whites reaching upward in a way that I thought might be Monet, but when I checked the back flap I was not really surprised to see that it was a Renoir. The way to tell would have been to look at the figure, the painter in his hat, all his energy turned toward his craft. Features, soft, almost indistinct, but the impression of the face is of concentration and happiness. He could be humming.

---

Apparently Renoir loved all craftsmanship. He had himself begun by painting porcelain and then window shades. His father was a very good tailor. Renoir used to lament the passing of know-how and the replacement of hand industries by machines. He had felt grateful to grow up in the old Tuileries neighborhood before it was torn down – all the stairways and niches and small corner carvings of the buildings bespoke the loving care of craftspeople. Women, he told his son, at their daily tasks, know how to live. “Around them I feel happy.”

---

In a state of happy engagement people are very close to the surface, much closer then we usually are able to be even with close friends, whose faces barricade them in reserve. Perhaps what I have taken for too much luster, too much skin, is really more unsettling, the close presence of people in a state to which we are no longer accustomed, as we may find the unsanitized smells from earlier eras – a barnyard, a field of clover, dried lavender in sheets – overwhelmingly, almost intolerably, sweet.

Reading Toward Renoir II

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

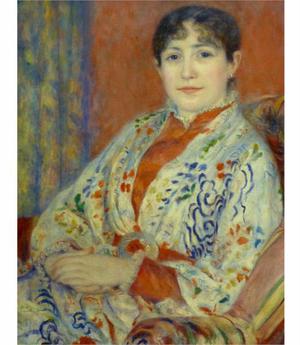

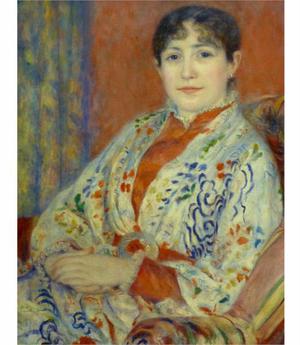

Renoir, Madame Hériot, 1882

I find that in reading Jean Renoir’s Renoir, my father, I am thinking of Maxim Gorki’s memoir of Chekhov, a most beautiful reminiscence. In particular of a story I have always loved, and which has to be quoted complete with Gorki’s introductory meditation. It is as follows:

I think that in Anton Chekhov’s presence everyone involuntarily felt in himself a desire to be simpler, more truthful, more one’s self; I often saw how people cast off the motley finery of bookish phrases, smart words, and all the other cheap tricks with which a Russian, wishing to figure as a European, adorns himself, like a savage with shell’s and fish’s teeth. Anton Chekhov disliked fish’s teeth and cock’s feathers; anything” brilliant” or foreign, assumed by a man to make himself look bigger, disturbed him; I noticed that whenever he saw any one dressed up in this way, he had a desire to free him from all that oppressive, useless tinsel and to find underneath the genuine face and living soul of the person. All his life Chekhov lived on his own soul; he was always himself, inwardly free, and he never troubled about what some people expected and others – coarser people – demanded of Anton Chekhov. He did not like conversations about deep questions, conversations with which our dear Russians so assiduously comfort themselves, forgetting that it is ridiculous, and not at all amusing, to argue about velvet costumes in the future when in the present one has not even a decent pair of trousers.

Beautifully simple himself, he loved everything simple, genuine, sincere, and he had a peculiar way of making other people simple.

Once, I remember, three luxuriously dressed ladies came to see him; they filled his room with the rustle of silk skirts and the smell of strong sent; they sat down politely opposite their host, pretended they were interested in politics, and began “putting questions”: “Anton Pavlovich, what do you think? How will war end?”

Anton Pavlovic coughed, thought for a while, and then gently, in a serious and kindly voice, replied: “Probably in peace.”

“Well, yes… certainly. But who will win? The Greeks or the Turks?”

“It seems to me that those will win who are the stronger.”

“And who, do you think, are the stronger?” the ladies asked together.

“Those who are the better fed and the better educated.”

“Ah, how clever,” one of them exclaimed.

“And whom do you like best?” another asked.

Anton Pavlovich looked at her kindly, and answered with a meek smile: “I love candied fruits… don’t you?”

“Very much,” the lady exclaimed gaily.

“Especially Abrikossov’s,” the second agreed solidly. And the third, half closing her eyes, added with relish: “It smells so good.”

And all three began to talk with vivacity, revealing, on the subject of candied fruit, great erudition and subtle knowledge. It was obvious that they were happy at not having to strain their minds and pretend to be seriously interested in Turks and Greeks, to whom up to that moment they had not given a thought.

When they left, they merrily promised Anton Pavlovich: “We will send you some candied fruit.”

“You managed that nicely, “ I observed when they had gone.

Anton Pavlovich laughed quietly and said: “Everyone should speak his own language.”

[Maxim Gorky, Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Andreyev. With an introduction by Mark Van Doren. Translator not given. New York: Viking Press, 1959, pp74-76.

Although the translator’s name is, astonishingly, nowhere given in the volume, I assume the translation is a good one and that the tiny hint of condescension in “not having to strain their minds,” is Gorki’s, though perhaps, under the influence of Chekhov, the younger writer felt no such thing and it is at the further remove of translation that the note has entered the composition. I am certain, though, and in part from reading this passage of Gorki’s, that the feeling is not Chekhov’s, as it seems it would not be Renoir’s. Chekhov’s idea of a person may be more complicated than Renoir’s – it does seem that the regrets and struggles of his figures have more bitterness in them – but, as in Renoirs, there is the sense in the stories that it is natural for people to be themselves, and that the task of the painter or the writer is to help them to circumstances in which they are.

Thin Air

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

We are in the air. The baby and I. She sleeps in my right arm; I type with my left thumb. Clouds below discrete cotton floaters, at our level cirrus band and behind that at sky's horizon higher piled. Despite glimpsed majesty, in airplane capsule thoughts inward, my mother, her grief, my father's study, which I cleaned while home, naturally, as if straightening a desk nearly my own, books and notes, small discoveries, the text by Confucius, a picture of my sister her head thrown back in happiness.

I forget that I am often in the sky. The way clouds look from above doesn't occur to me; I have to force myself to think of it. They're cut out of life, these air interludes. But I notice the baby thinks of the sky as a place one can go. When the elephant jumps the fence or the bear sneezes and the animals go flying she holds the book up in the air as she does her tiny wooden plane when we talk of flying. This week she missed her Dad intensely and it seemed she had the idea that he had gone, not to a conference in Greece, but to the moon. 'Moon,' she said when we spoke of him, and once late, unable to fall asleep, she insisted we go out and look for the moon in the night sky.

She has a book in which a little girl asks for the moon and her father climbs a long ladder and brings it down for her. I had forgotten the book earlier this week, the night of the rare equinoctic moon, apparently larger and closer than in decades, which I wanted badly to get up at four in the morning to see, but instead dreamt of getting up to see and in the dream caught only the last sight, huge, pale orange and planetary, with rings like Saturn, slipping over the horizon. In the dream I told my mother and sister how beautiful it had been. I did then wake up and go out to look but it was already gone. The next day I told them of the dream and felt my father, planetary, hovering. But not to be reached by the baby and me, so far from these clouds even as we descend through them, much farther I think than Confucius was from his skies or I would not have written this into my cell phone as we fly.

Private Collection II (with Paul Valéry)

Monday, June 3, 2013

Some weeks later I remembered that I had read something about Berthe Morisot, long ago, in a book by Paul Valéry, a collection of occasional pieces about painting with the somewhat misleading title

Degas, Manet, Morisot. I hurried back to read the passages on Morisot, three really, altogether perhaps ten pages.

The man who wrote the introduction to the volume decided, rather ruefully, that, despite living among the Impressionists and being himself so intelligent, Valéry’s writing about them was only in a limited way perceptive. The poet seems in a way to take the painters and their achievements for granted. But, for me, these few passages, coming as they do from a man who was married to one of Morisot’s nieces, and lived in the house that had been Morisot’s, offer something more than useful about “Tante Berthe.” Morisot’s daughter and her cousins had grown up surrounded by paintings: Morisot’s and also those of their close friends – Renoir, Degas, Monet. Berthe Morisot was Berthe Manet, as she was married to Édouard Manet’s brother, Eugène. I’ve read Morisot’s correspondence with Stephane Mallarmé now, too, and the letters give the impression of life intensively lived among a few choice acquaintances. “Rare and reserved,” Valéry says; the work, too, is private.

Of all the artists he encountered, Valéry weighed it out, Morisot, he thought, was the one:

to live her painting and to paint her life, as if the interchange between seeing and rendering, between the light and her creative will, were to her a natural function, a necessary part of daily life. It is this which gives her works the very particular charm of a close and almost indissoluble relationship between the artist’s ideals and the intimate details of her life. Her sketches and paintings keep closely in step with her development as a girl, wife, and mother. I am tempted to say that her work as a whole is like the diary of a woman who uses color and line as her means of expression. (119)

This might be a subtle way of dismissing a woman’s work – another woman damned with praise for her understanding of the quotidian – but it doesn’t strike my ear that way. Valéry also says of her canvases:

Made up of nothing, they multiply that nothing, a suspicion of mist or of swans, with a supreme tactile art, the skill of a rush that scarcely feathers the surface. But that featheriness conveys all: the time, place, and season, the expertise and swiftness it brings, the great gift for seizing on the essential, for reducing matter to a minimum and thus giving the strongest possible impression of an act of mind…. (121)

The surprising texture of paint in her handling, the odd inward structure of the material, these phrases of Valéry’s, give something to think about.

Landscape of La Creuse, 1882, Private Collection.

Woman Hanging Out the Wash, 1881, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Young Woman in a Rowboat, Eventail, 1880, Private Collection.

Citations from: Valéry, Paul,

Degas, Manet, Morisot. Translated by David Paul. Edited by Jackson Matthews. With an Introduction by Douglas Cooper. Princeton University Press: 1960.

Paintings: see the Athenaeum.

Private Collection

Monday, May 13, 2013

Morisot, Clark Institute

A small watercolor by Berthe Morisot was the most surprising thing I saw on our trip to New York. At the Frick, on loan from the Clark, in that basement space they use for special exhibitions and works on paper, in an assortment of drawings by French Impressionists. The watercolor is of a dark boat floating in green water among other crafts – masts, bow, lines for sail and anchor, a few indistinct figures moving about their work. Colors wonderful – shadows of boats reflecting darker green below, sense of movement, mass, buoyancy. Apparently she drew while herself on a neighboring boat and relished the difficulty of getting the lines while she herself went up and down. A much better draughtsman than I had realized, learning from Turner’s watercolors in ways that I’ve not seen others do, allowing the colors to make a structure. Who is she? Berthe Morisot. The images I know are of her, especially Manet’s portraits, not by her. At the Met later that day four or five really wonderful paintings by Morisot as part of their “Impressionism and Fashion” exhibition. The women in these paintings – reclining or sitting, looking in mirrors or at us – emerge out of a shaded and subtly modulated atmosphere. The air itself is thick with paint that condenses in the figure. Clothes are beautiful. A manifestation of what animates their wearers. These women have not been dressed, they dress themselves. I had little time, but tried to look carefully at just these paintings, promising myself that I would spend more time with them one by one in the museums where they reside. In the gift shop, quickly scanning the one book on Morisot, I saw to my disappointment that nearly all her work is in private collections.

Autobiography Today

Friday, April 26, 2013

When I was teaching more, my students, undergraduates and graduates, people who were somewhere between eighteen and seventy-six years old, were all writing their memoirs. I railed against this at first, particularly with younger students; such was my reputation for impatience with the form that I even had students hesitatingly ask if it would be all right to use the first person. I did see that this was a somewhat ridiculous position for an admirer of Montaigne and David Foster Wallace to be in.

I conceived of different ways to explain the distinction: between essays full of the writers’ personality, even experience [Woolf, Montaigne] essays that nevertheless needed the world in order to become shapely and coherent, and accounts of incident or recovery that held their narrative internally, internal to the life of the writer. It became increasingly difficult to maintain these kinds of distinctions.

It is not simply a series of coincidences that in the last ten or twenty years bookstores have sections and special tables devoted to memoir, literary prizes have begun to be awarded in the category of memoir or autobiography, literary careers can be built out of a series of memoirs and serious novelists no longer confine themselves to autobiographical fiction but often write at least one memoir. There has been one of those large changes in literary expression, like the novel replacing the verse epic, or the irregular poem replacing one with rhyme and meter.

The puzzle of why, now, the literary endeavor so often begins with the first person is preoccupying. It certainly does not suffice to point to confessional talk shows, poetry and musical lyrics; or to reality tv; the rise of documentary films; facebook pages, blogs, iphone self-documentation. All these must be additional results of some common deeper cause. The isolation of the modern self? Uneasiness with imagination? The general distrust of the general principle, felt to be falsely homogenizing, even colonial in intent? (These may not really be distinct either.) The fear that one’s own experience will be swallowed up by technology, advertising, the speeding years? The rootless nation of immigrants, bereft of continuous tradition, trying at least to get something down before everyone moves again? The end of religion? The gradual evaporation of the reality of other people? The focus of capitalism on the individual as acquisitive being, acquirer even of experience?

Self-absorption, people have said to me impatiently when I broach the subject, sometimes before hurrying on to talk of their own projects. What if the impulse is a healthy one – to restore, or at least record, the damaged self, to take seriously one’s own corner of the universe, to try to communicate by beginning from a beginning. If the fragments of ruined culture are what we have perhaps it is right to start with one’s own experience of them.